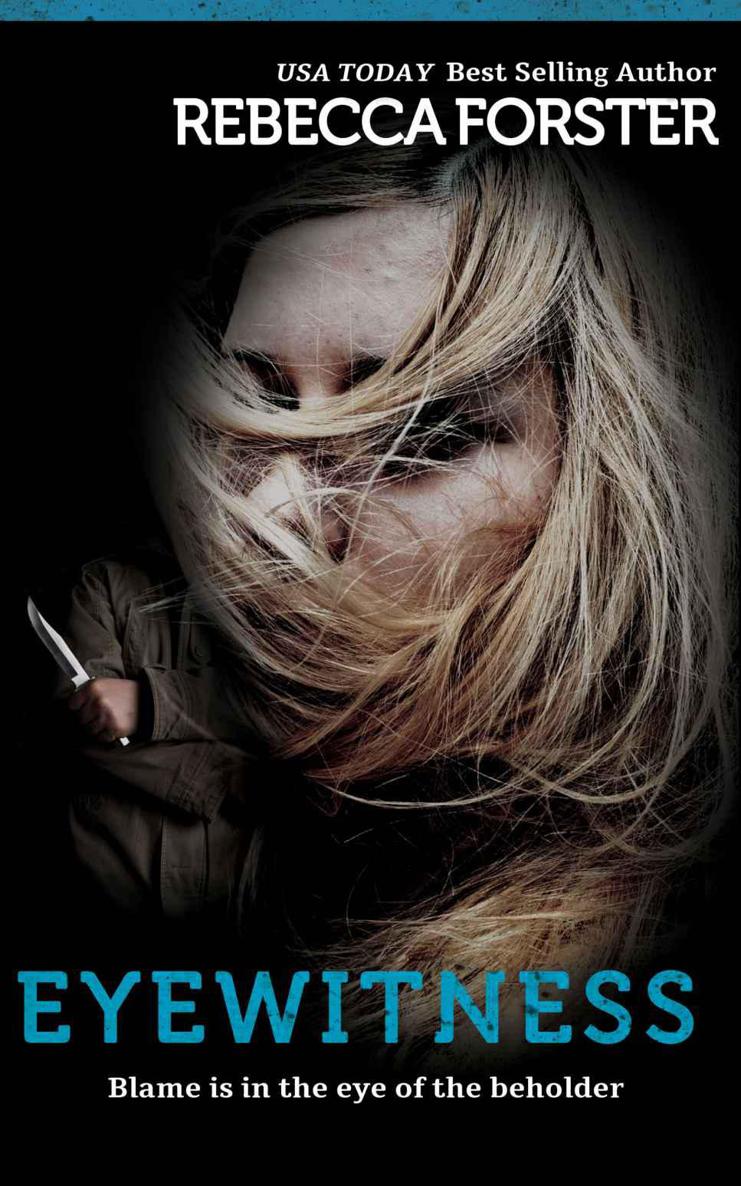

Eyewitness (Thriller/Legal Thriller - #5 The Witness Series) (The Witness Series #5)

Read Eyewitness (Thriller/Legal Thriller - #5 The Witness Series) (The Witness Series #5) Online

Authors: Rebecca Forster

E

yewitness

By

Rebecca Forster

Eyewitness

Copyright © Rebecca Forster, 2013

All rights reserved

Cover design

www.designcatstudio.com

The ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be

re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to Amazon.com and purchase your own copy.

Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

For My Son, Eric

Thanks for Sharing the Adventure

Writing is not a lonely profession when you have excellent

friends to cheer you on. Many thanks to Hamilton C. Burger, fabulous author of children’s books, Jay Freed, fabulous keeper of the emoticons, Bruce Raterink most fabulous bookseller and buddy ever, Judy Kane fabulous eagle eye, and Jenny Jensen who is just plain fabulous. Steve, couldn’t do it without you and to my eldest son, Alex, thanks for your unshakeable faith.

CONTENTS

Author's Note

:

This book was inspired by my trip to a remote village in Albania where my son served as a Peace Corps Volunteer. I le

arned about ancient Albanian laws and modern crime. I also learned about the legend of Rosafa. Rosafa, a national heroine, was predestined to be encased in a castle’s stones so that the walls would stand strong. Worried about her infant son, she accepted her fate on the condition that her right breast be exposed to feed her newborn son, her right eye to see him, her right hand to caress him, and her right foot to rock his cradle. The Albanian peoples’ history, resilience, sacrifice for family, and adherence to a code of honor are a reality. Their hospitality to a visitor was humbling.

Eyewitness

is about the collision of two cultures, two sets of rules, and two visions of justice and the battleground is Hermosa Beach.

1966

Yilli had been left to guard the border, a chore he thought to be a useless exercise. No one wanted to come into his country, which meant he was guarding against his countrymen who wanted to get out. But even if those who were running away got by him (which more than likely they would), the government had mined the perimeter. It would take an act of God (if God were allowed to exist) guiding your feet to step lightly enough so that you didn’t blow yourself up. Yes, it would take quite a light step and a ridiculous will and he, Yilli, didn’t think there was anything outside his country that was any better than what was inside. So, he reasoned, there was no need for him to be sitting in the cold on this very night with a gun in his hand.

That was as far as Yilli’s thoughts went. He was a simple man: wanting for little, satisfied with what he had. Which was as it should be. All of these other things – politics and such – only served to make life complicated and very miserable. In his father’s age and his father’s before that, a man knew what was wrong and what was right because the Kunan said it was so. A man protected family above all else, not a border that no one could see.

Yilli shifted, thinking about his mother, his father’s time, but mostly about his comrades who believed they had tricked him. His mother had named him Yilli and that meant star. His comrades reasoned he was the best to watch through the night, shining his celestial light on any coward who tried to breach the border. Then they laughed and went off to have some raki, and talk some, and then fall asleep sure that they had fooled Yilli into thinking he was special.

Yilli smiled. Simple he may be, stupid he was not. Star, indeed. Shine bright. Hah! They knew he was a good boy, and he knew that they made fun with him. That was fine. His comrades were all good boys, too. None of them liked to be in the army or to carry arms against their countrymen, but that was the way of the world and they took their fun when they could.

Yilli picked up a stone and tossed it just to have something to do. He heard the click and clack as it hit rock, ricocheted off more stone, and rolled away. Rocks were everywhere: mountains grew from them, the ground was pocked with them, the houses were hewn from them. He threw another stone and then tired of doing that. His back ached with his rifle slung across it, so he slipped it off, leaned it against his leg, and sighed again. He sat down on a rock, spread his legs, and let the rifle rest upon his thigh.

He, Yilli, was twenty years old, married, and he would soon have a child. He should not be sitting on a rock, afraid to walk out to pee in case he should be blown to pieces. He should not be sitting in front of a bunker made of rock, throwing rocks at rocks. He had a herd of goats to tend in his village. Or at least he thought he still had a herd of goats. Sometimes the government took your things and gave them to others who needed them more. He didn’t need much, but no one needed his goats more than he did.

Yilli’s mind and body shifted once more.

He wished he had a letter from his wife. That would pass the time. But he was told not to worry. The state would see that he got his letters when he deserved to get them. But how could he not worry? He loved his young wife. She was slight and pretty, and he had heard things about childbirth. It could tear a woman up and she could bleed to death. Then who would take care of the child? If the child survived, of course. And, if the little thing did survive, milk was hard to come by. Not for the generals, but for him and his family it was. If he didn’t have his goats and his wife died, he would be screwed.

Yilli picked up another stone. He held it between his fingers, raised his arm, and flung it away. The sound of rock hitting rock echoed back at him. He reached for one more stone only to pause before he picked it up. Yilli raised his head and peered into the dark, looking toward the sound that had caught his attention.

Fear ran cold up his spine and froze his feet and made his fingers brittle. His big ears grew bigger. There was a scraping sound and then a cascade of displaced stones. Slowly, he sat up straighter and listened even harder. Someone or something had slipped. But how could that be? Everyone in these mountains took their first steps on stone and walked their journey to the grave on it. Yilli knew what every footfall sounded like and out there was someone stepping cautiously, nervously, hoping not to be found out. They were frightened. That was why they slipped.

Yilli raised his eyes heavenward just in case the government was wrong and there was a God. He thought to call out for his comrades, but that would only alert the enemy. That person might cut him down before his cry was heard. It was up to him, Yilli the goat herder, to protect his country and this border he could not see.

He rose, lifting his rifle as he did so. The gun was heavy in his hands. His breath was a white cloud in the freezing air. Above him the moon shined bright and still he could not see clearly. He narrowed his eyes, looking to see who or what was coming his way. He comforted himself with the thought that it might be a wandering goat, or a dog, or a sheep, but he knew that could not be right. The hour was too late and livestock would not be out. Also, animals were more sure-footed than humans. Yilli swallowed and his narrow chest shuddered with the beating of his heart.

“Who is there?” He called out, all the while wishing he were in bed with his pregnant wife, the fire still hot in the hearth, the goats bedded down for the night. “Who is there? Show yourself.”

He raised his rifle. The butt rested against his shoulder. One hand was placed just as he had been shown so that his finger could squeeze the trigger and kill whoever dared approach. His other hand was on the smooth wood of the stock. He saw the world only through the rifle sight: a pinpoint of reality that showed him nothing.

The sound came again, this time from his right. He swung his weapon. There was sweat on his brow and on his body that was covered by the coarse wool of his uniform. His fingers twitched, yet there was nothing but the mountain in the little circle through which he looked.

Sure he now heard the sound coming from the left, Yilli swung the rifle that way only to snap it right again because the sound was closer there. That was when he, Yilli, began to cry. Tears seeped from his eyes and rolled down his smooth cheeks, but he was afraid to lower the rifle to wipe them away. The tears stopped as quickly as they had begun because now he saw his enemy. It was only a shadow, but this was no goat or dog. This was the shadow of a man and he was coming toward Yilli.

“Ndalimi! Do not come closer. I will shoot. Ndalimi!” Shamed that his voice trembled like a woman, he stepped back and took a deep breath.

“Ndalimi!” Yilli shouted his order again, but the man didn’t stop. He didn’t even hesitate. It appeared he either had not heard Yilli, or was not afraid of him or, was simply desperate to be away.

Yilli lowered the muzzle of the rifle and raised his head to see more clearly. He blinked, thinking he only knew one person so big. But it could not be Konstadin coming up the mountain, moving from boulder to boulder, sneaking from behind the rock. Still, it was someone as big as Konstadin. Yilli snapped the rifle back to firing position. If it had been Konstadin, the man would have called out to him in greeting or to let him know that he had news from home. But if it were Konstadin bringing news of Yilli’s wife, how did he know to come to this place? He had

told no one of his orders. Yilli became more afraid now that there were all these questions. He had also become more determined because he, Yilli, was not just a good boy, he was a man in the service of his country.

“Ndalimi!” Yilli barked, surprising himself, sounding as if he should be obeyed. His grip on his rifle was so tight his arms and fingers ached.

“Yilli.”

He heard the hoarse whisper that was filled with both hope and threat, but all Yilli heard was an enemy’s voice. He saw now that there were two of them. Perhaps there were more men coming, rebels ready to kill him in order to take over the government. These men could be desperate farmers wanting Yilli’s rifle so that they could protect their families. One of them might hit him or stab him and the other would take the rifle. They might shoot him with his own gun.

Tears streamed down Yilli’s face now. His entire body shook, not with cold but with a vision of himself bleeding to death without ever seeing his wife, or his child, or his goats.

With that thought two things happened: the giant shadow loomed up from behind a boulder and the rifle in Yilli’s hands exploded. His ears rang with the crack of the retort; the flash from the muzzle seared his eyes. Near deaf as he was the scream he heard was undeniable.

From the right a smaller man ran toward the little clearing and threw himself to the ground. He landed on his knees just as the moon moved and brightened the mountain. Yilli, who had been blinded, now saw clearly. It was not a man at all who had run fast and sure over the rocks but a boy. It was Gjergy. It was Gjergy who cried out to the man lying on the ground. The boy pulled at him and wailed and held his arms to the sky. Yilli could see the bottoms of the other man’s boots and the length of his legs. He saw that man was not moving.

As if in a dream, Yilli moved forward until he was standing beside them, the smoking rifle still in his hand. It was Konstadin, Gjergy’s brother, man of Yilli’s clan, lying on the ground, his arms thrown out, and his eyes wide open as if in surprise. His shirt was dark with the blood that poured out of his broad chest. Then Yilli realized that this was not Kostandin at all, it was only his body. Eighteen years of age and he was dead by Yilli’s hand.

“What have I done?”

He had no idea if he screamed or spoke softly. It didn’t matter. What was there to say? That he was a reluctant soldier? That he didn’t know how this had happened? That he was sorry to have taken a precious life? How could he make Gjergy, this boy of no more than twelve years, understand what he, Yilli, did not?

The rifle almost fell from Yilli’s hands. His heart slammed against his chest as if trying to tear itself from his body and throw itself into the hole in Konstandin’s. He, Yilli, wanted to make Konstandin live again, but the cold froze his legs, his arms, his very soul. His breath came short and iced in front of his eyes. His head spun. He blinked, suddenly aware that Gjergy was rising, unfolding his wiry young body. Yilli thought for a minute to comfort the boy, explain to him that this had been a tragic mistake, but Gjergy was enraged like an animal.

“Blood for blood,” he screamed and lunged for Yilli.

Unencumbered by Gjergy’s grief, Yilli moved just quickly enough to save himself. Gjergy missed his mark when he sprung forward and did not hit Yilli straight on. Still, Yilli fell back onto the ground with the breath knocked out of him. Instinctively he raised the rifle, grasping it in both hands, and holding it across his body to ward off the attack.

“Gjergy! It is me!” Yilli cried, but the boy was mindless with rage and would not listen.

“You murdered my brother.” Gjergy yanked on the rifle, but Yilli was a man eight years older. He was strong and fear made him stronger still.

“No! No! It was an accident,” Yilli cried.

Just as he did so, a bullet whizzed past them. Then another. And another. Yilli rolled away fearing his comrades would kill him and praying they did not kill Gjergy. He could not imagine bringing more sadness on the mother of those two good boys.

Gjergy bolted upright, scrambling off Yilli, running away faster than Yilli thought possible. He ran like the child he was, disappearing into the night, leaving only his words behind.

Blood for blood.

Gjergy had not listened that Yilli was only a soldier and that this was not killing in the way the Kunan meant. He had no time to remind the boy that the old ways were outlawed, and that he must forget that he had ever said such a thing. If he did not, there would be more trouble.

Suddenly, hands were on Yilli. His comrades had come running at the sound of the shot. Two of them ran after Gjergy even though they all knew they would not find him.

“Stop. He is gone.” Yilli called this as those who remained pulled him to his feet.

“Who was it?” one of them asked.

“No one. A stranger,” Yilli answered.

“This is Konstadin,” another soldier called out.

“The one with him was a stranger.” Yilli repeated this, unwilling to be responsible for a boy suffering the awful punishment that would be imposed should he be found out.

Then no one spoke as they stood looking at the body. All of them knew what this meant. It was Skender, captain of them all, who put his hand on Yilli’s shoulder. It was Skender who said:

“It is a modern time. Do not worry, Yilli.”

Yilli nodded. Of course, he did not believe what Skender told him any more than young Gjergy had believed him when Yilli tried to say that the killing had been an accident.

Though his comrades urged him to come to camp to rest, though all of them offered to take his watch now that this thing had happened, Yilli went back to sit on the rock where only a few minutes ago he had been thinking about his wife and his child. He put his rifle on the ground and his head in his hands.

He was a dead man.

2013

Josie slept alone the night the storm came up from Baja and crashed hard over Hermosa Beach. It was as if Neptune had surfaced, blown out his mighty breath, and wreaked godly havoc on Southern California with an all out assault of thunder, lightning, and hellacious wind. Yet, because she was curled under her duvet, because her bedroom was at the back of the house, it was no surprise that Josie wasn’t the one to hear the frantic knocking on the door and the screaming that came with it.