Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney (33 page)

Read Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney Online

Authors: Howard Sounes

Tags: #Rock musicians - England, #England, #McCartney, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Paul, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

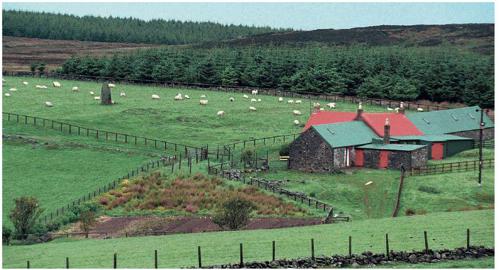

As the Beatles fell apart, Paul and Linda retreated to their remote Scottish farm, High Park. They are seen here on the property in 1971, with their pet dog Martha.

Visitors to Paul and Linda’s Scottish farm were often surprised by how small and basic it was - just a little stone house with an iron roof. The location was, however, private and beautiful, with an ancient standing stone directly in front of the cottage.

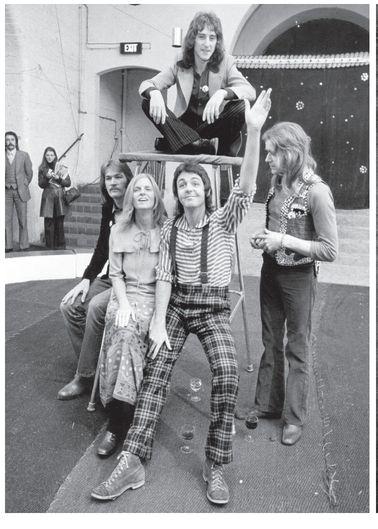

In 1971, Paul launched his new band, Wings, featuring (clockwise from top) guitarists Denny Laine and Henry McCullough, Paul and Linda and drummer Denny Seiwell.

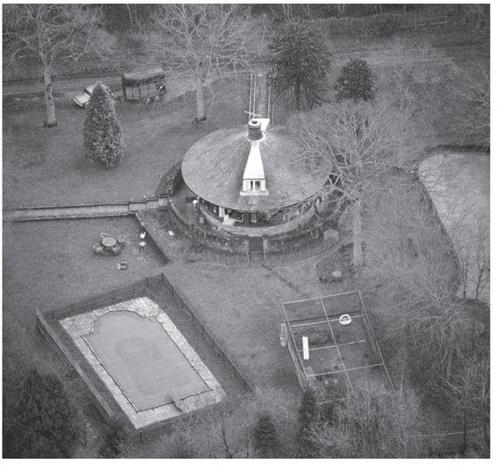

. Paul and Linda bought Waterfall, a rotunda hidden in woodland near the village of Peasmarsh, East Sussex, as a second country retreat in 1973. They subsequently made the house their principal home.

12

WEIRD VIBES

THE BEATLES AT WAR

Shortly after returning home from India, in May 1968, the Beatles convened at George Harrison’s home in Esher to run through 23 new songs that became the basis of their next album,

The Beatles

, better known as the

White Album

(and hereafter referred to as such) because it was packaged in a plain white sleeve. John brought the largest number of songs to the demo session including ‘The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill’, ‘Dear Prudence’, ‘Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey’, ‘I’m So Tired’, ‘Julia’, ‘Revolution’, ‘Yer Blues’ and ‘Sexy Sadie’, the last being a swipe at the randy Maharishi. George’s contributions were notably ‘Piggies’ and ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, while Paul demonstrated ‘Back in the USSR’, ‘Blackbird’, ‘Honey Pie’, ‘Junk,’ ‘Mother Nature’s Son’, ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’ and the delightfully silly ‘Rocky Raccoon’.

Here then was the backbone of the only double studio album the Beatles recorded, a relative rarity in the music industry at the time, with songs to spare. Moreover, here was a wide range of musical styles, from the country sound of ‘Rocky Raccoon’ via Paul’s Beach Boys-on-the-Volga pastiche (‘Back in the USSR’) to the experimentation of ‘Revolution 9’, together with more traditional songs of love and regret, graced by some of the best lyrics the boys ever penned.

The

White Album

is a boldly, unapologetically ambitious and arty record. Gone are the corny songs of Beatlemania. The Beatles were now men making mature, reflective music, the quantity and variety of which sets the

White Album

apart as one of their greatest achievements. This important and welcome musical variety - the variety of a box of Good News chocolates, which George references on another of his songs, ‘Savoy Truffle’- is partly a result of the fact the Beatles were no longer a harmonious team. They were increasingly at war with one another, often working individually on their own songs, sniping at each other and at odds with the studio staff who’d served them for years, which had an unexpectedly positive result in that the set-up changed; old faces left, new people and new studios were used. The format was shaken up, the Beatles getting away from making the self-consciously clever albums of the mid-1960s, culminating in

Sgt. Pepper

, allowing themselves instead to spread out and do as they pleased, however wild the music sounded, and indeed the wilder the better. It is when the Beatles seem to go too far that the

White Album

is most interesting.

In a way Yoko Ono is to be thanked for this shake-up in the Beatles’ working methods, even if her presence ultimately proved toxic. Having usurped Cynthia and moved into Kenwood, Yoko went everywhere with John nowadays, including attending the opening of the Beatles’ new King’s Road tailoring shop on 23 May. It soon became clear Yoko was not a docile Beatles partner in the mould of Cyn, Mo and Pattie. Yoko was also unlike Jane Asher, who had a career of her own but was assiduous in not getting mixed up in Paul’s work. ‘She was great because she didn’t interfere with anything, she had her own life to lead,’ Measles Bramwell says approvingly. In contrast Yoko interfered constantly.

When the band assembled in Studio Two at EMI to begin their new album, on Thursday 30 May 1968, Paul, George and Ringo were flabbergasted to find Yoko sitting with John, apparently intending to stay there while they recorded. In the past the Beatles hadn’t even liked Brian in the studio. Select friends were invited to watch sessions, it was true, and occasionally guests were asked to sing a backing vocal or shake a tambourine at a special event like

Our World

, but the Beatles’ day-to-day studio work was, in the union language of the day, a closed shop. Yoko broke the rules. She intruded, sitting with the boys among the mike stands and baffles, and when they began John’s ‘Revolution’, a blues that referenced the revolutions and uprisings sweeping the world, from Mao Tse-tung’s Cultural Revolution to the student protests in Paris, Yoko started contributing vocals - one couldn’t say

singing

- rather she yelped, moaned and squawked along with her lover.

John then decided he might get a better vocal if he lay down on the floor to sing this strange new song, to which he devoted the following two weeks. Ultimately, there were three versions of ‘Revolution’, or perhaps better to say variations on the theme: a blues crawl, ‘Revolution 1’, with

shooby-doo-wah

backing vocals; a faster hard-rock version that would appear on the flip-side of the Beatles’ next single; and the radically different ‘Revolution 9’, a sound collage in the

musique concrete

style; that is music created by combining a variety of recorded sounds, as Stockhausen did in 1956 with

Gesang der Jünglinge

. Although the form had been around for a decade, it was new to rock.

Then John suggested Yoko dub a backing vocal - instead of Paul. McCartney ‘gave John a look of disbelief and then walked away in disgust’, recalls studio engineer Geoff Emerick, who’d worked on every Beatles album since

Revolver

, but wasn’t enjoying this one. Before long, Yoko was in the control room, venting her opinion on what they’d recorded so far. ‘Well, it’s pretty good,’ she told George Martin of one take of ‘Revolution’, ‘but I think it should be played a bit faster.’ A line had been crossed. John was allowing this strange little woman, with whom he’d become infatuated, to enter into and meddle with a band that, aside from small disagreements, had hitherto been four friends united against the world. It was a shocking breach of etiquette. ‘It just spoiled everything,’ laments Tony Bramwell, who blames Yoko ultimately for the break-up of the band. ‘Yoko was the acerbation (sic) in the studio that caused the split between all of them. George called her the witch; Ringo hated her; Paul couldn’t understand why somebody would bring their wife to work.’

31

There was some sexism in the attitude to Yoko, even a touch of xenophobia. Unkind remarks were made about ‘the Jap’. But one can see why Paul, George and Ringo were irritated. Yoko wasn’t a musician, at least not as they were, but the latest flaky character to have taken John’s fancy. At the same time, she was a catalyst for change.

When the Beatles were recording, they normally started with a John song, then a Paul song. This time they went straight from ‘Revolution’ (not that it was finished) to a Ringo song, ‘Don’t Pass Me By’, which showed how strange things had become. Stranger followed. It was unheard of for band members to leave London while an album was in production. Yet Paul, George and Ringo now left John and Yoko to fiddle with ‘Revolution’, and amused themselves elsewhere: George travelling to California to take part in a documentary about Ravi Shankar, Ringo going with him for company; while Paul went up north to be best man at his brother’s wedding.

Mike McCartney married his fiancée Angela Fishwick on Saturday 7 June 1968 in North Wales, the service conducted by Buddy Bevan, the relation who’d married Jim and Ange four years earlier. Mike’s show business career had taken off in recent months, the Scaffold scoring a novelty hit with ‘Thank U Very Much’, making Paul’s brother a celebrity in his own right under the stage name of Mike McGear. Mike deported himself like an archetypal Sixties’ dandy, coming to his wedding in a flamboyant white suit, black shirt and groovy white neckerchief. In contrast, Paul wore a conservative suit and tie to the wedding. Jane was also simply dressed. The couple posed obligingly for pictures with the bride and groom after the service, then everybody went back to Rembrandt to celebrate the union, Paul reading out the congratulatory telegrams. He and Jane seemed happy. ‘They could not have been more lovey-dovey and it was in very private circumstances where they didn’t have to put anything on for the press,’ recalls Tony Barrow, who was present. Yet as soon as he got back to London, Paul took another woman to bed.

When Paul went on American television asking the public to send Apple their ideas, Francie Schwartz was one of those viewers who took the star at his word. A 24-year-old advertising agency worker from New York, Francie bought a plane ticket to London and presented herself at the Apple office with a movie script she wanted produced. She persuaded Tony Bramwell to let her see Paul. ‘I only introduced them because she had this strange film idea which I thought would appeal to him,’ recalls Bramwell. It wasn’t actually that difficult to meet Paul in this way. Unlike his fellow Beatles, Paul came into the Apple office most days, and made the time to listen to at least some of the new ideas that came in. Anybody who was personable and persistent had a chance of having a word with the star. It helped if you were an attractive young woman. In fact, Francie was a rather plain woman, with prematurely grey hair. Yet Paul found her pretty enough. ‘Am I impressing you now, with my feet up on this big desk?’ he asked, as they flirted in his office.

Nothing happened between them until after Mike’s wedding, when Jane had gone back to the Bristol Old Vic. With Jane out of the way, Paul came over to Francie’s Chelsea flat, with Martha the dog, and jumped into bed. ‘The sheepdog followed us into the bedroom to watch,’ Francie wrote in her candid memoir,

Body Count

. She called Paul Mr Plump, for reasons unexplained. Likewise, he called her Clancy. It was clear to Clancy that, despite being engaged to be married, and putting on such a good show at his brother’s wedding, Mr Plump and his fiancée were not getting along. Paul seemed to think Jane had a boyfriend in Bristol, and rather than try and win her back he chose to get even with her, allowing Francie to move into Cavendish with him while Jane was away, also getting his new girlfriend a job in the Apple press office. He even invited Francie along to EMI recording sessions - surely a touch of tit for tat. While John and Yoko worked together on ‘Revolution 9’ in Studio Three at Abbey Road, Paul took Francie next door to watch him record ‘Blackbird’ in Studio Two. A greater contrast to ‘Revolution 9’ is hard to imagine than this pretty, guitar-picking tune, the melody based on a Bach bourrée, while the lyric, recorded shortly after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr, was meant as a metaphor for the American Civil Rights struggle. ‘As is often the case with my things, a veiling took place, so, rather than say “Black woman living in Little Rock” and be very specific, she became a bird, became symbolic …’

Paul then left Francie and the difficult

White Album

sessions to go on a business trip to Los Angeles with Apple staff men Ron Kass and Tony Bramwell, plus his school friend Ivan Vaughan. The threesome flew to LA via New York where, in the transit lounge at JFK, Paul called and left a message with Linda Eastman’s answering service, saying he was on his way to the West Coast and could be reached at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Arriving in LA several hours later, Paul checked into the pink hotel on Sunset Boulevard, taking Bungalow Number Five, which was favoured by Howard Hughes, then hit the clubs. Word soon got around that Paul was in town. ‘He pulled a few slappers [and] by the time we got back to the Beverly Hills Hotel there was queues around the block of girls trying to get in,’ says Bramwell.

The next day, after fooling about by the pool with the girls he’d met, Paul went to see Capitol Records chief Alan Livingston, then came back to change before his next engagement. ‘And there was Linda!’ recalls Bramwell. ‘Sitting on the doorstep.’ Having received Paul’s message, Linda had taken the first available flight from New York to LA. ‘So immediately Paul got me to clear away all the birds, and just locked himself in the room with her.’ That night Paul attended to the main bit of business he had come to California for, which was making a personal appearance at a Capitol Records sales convention, screening a promotional movie about Apple, and telling the executives that future Beatles records would appear under the Apple label (though the band still remained tied to EMI). Having played the businessman, Paul returned to Linda at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

At this stage another girlfriend showed up. One of the local calls Paul had made when he arrived in Los Angeles was to actress Peggy Lipton, his bedfellow on two previous trips to LA. Seemingly, he was ringing around to see who was available. Despite the fact Peggy was now living with the record producer Lou Adler, she hopped in her car and sped over to the Beverly Hills Hotel, where she found a number of young women already waiting outside Bungalow Five. Measles told Peggy that Paul was sleeping - it was 4 o’clock in the morning - and that when he got up they were going out on a boat with the film director Mike Nichols. Peggy decided to wait. When Paul emerged from his room at 8:00 a.m., Peggy figured she was on for the boat trip. ‘As I gathered my things, preparing to join him, I spotted a woman coming out of the bedroom in Paul’s bungalow,’ Peggy later wrote. ‘Apparently, she had shown up before I arrived, and Paul, in his altered state, had forgotten I was on the way.’ Peggy watched tearfully as Paul and Linda Eastman ran for a limousine that took them to the harbour. This was the end of Peggy and Paul.

Paul and Linda spent the day together on Mike Nichols’s motorboat, the

Quest

, drinking champagne, eating bacon sandwiches and canoodling like love birds. ‘They were absolutely inseparable. It was like instant,’ notes Bramwell. ‘She was perfect for him: motherly …’ (Tony figured Paul had been looking for a mother substitute) ‘… big-breasted, and she had a

je ne sais quoi.

’ Like Paul, Linda was also a dedicated pot-head. She’d brought a bag of grass with her, which they dipped into, becoming closer as they got stoned, really close in the way John and Yoko were. ‘We were all conscious of - and somewhat amazed by - the depth of feeling Paul obviously had for Linda,’ adds Bramwell, noting that when they checked out of the Beverly Hills Hotel the next day Paul and Linda were ‘like Siamese twins, holding hands and gazing into each other’s eyes all the way to the airport’.