Face (32 page)

Authors: Aimee Liu,Daniel McNeill

Yi. Er. San.

One line. Two lines. Three lines. Now I was too far inside the borders.

“No good,” Li said. “Too little, too much is not just right.”

“How can drawing a line be so hard!”

“You think too much, try too much. Let brush and ink think, you will do better.”

“Maybe I’m just not good at this.”

“Your grandfather was great scholar. Maybe these his brushes and ink. ‘No good’ is no excuse for you. You know? You work hard,

think less, you be okay.”

Once again he seemed to know more about my family than I did, but I’d given up asking how he came by these details.

“It’s too much like art. I’m not good at art.”

“Not art,” he said. “Come.”

He took my hand and led me out into the gathering thunderstorm. “Chinese writing is like wind and rain.” He lifted my palm

toward the east. Push push release. Push push push release. Push release.

I felt the rhythm of the weather changing in my bones.

“Like sound.” He raised my hand to his lips and counted:

“Yi. Er. San. Si. Wu. Liu. Oi. Ba. Jiu. Shi.”

I felt the rhythm of Lao Li’s words moving beneath my fingertips.

“Like breath.” He placed my hand on my chest. Up down. Up down. Up down.

I felt the rhythm of my own life. Strong, steady, stable.

“Everything connect.” Li linked his fingers. “You breathe alone. I breathe alone. But is all same breath.” He grinned and

whipped up the wind with his arm.

“Old time, new time,” he said. “All same time.”

The rain, which had been a fine drizzle, turned to heavy drops.

“Water in clouds, in river. But is all same water.” He caught a handful and pushed it through his hair. The wetness glistening

on his forehead made him look vibrant, not exactly younger but as if he’d been mystically freshened. It was like some kind

of blessing.

Li stuck out his tongue and drank the rain. Dirty rain, city rain, I thought—but never mind. I, too, threw back my head, let

the downpour soak my face and hair.

And wept again for Johnny. For the knowledge that he would have loved this moment; for the faith I still did not quite have

that my father and Li were right about Johnny always being there with me, around in his own way.

We stayed like this as the storm pressed on. Lao Li laughed as I wept and the rain washed away my tears.

The weather was clearing when my father found us. I’d stopped crying. Li and I were not talking, just standing side by side

and watching the sunshine patch through the clouds. I didn’t notice Dad until he called my name, but Li’s whole body was turned

as if he’d been tracking him for some distance. Li’s lips were parted, showing just a sliver of gold teeth. His eyes were

open wider than I could remember seeing them, and he didn’t blink. With his hair slicked back by the rain he looked hungry.

Starving.

My father slowed as he neared our end of the block. He was wearing one of those dime-store pocket raincoats that never unwrinkle,

an ugly pinkish color with his checked shirt showing through. The hood had

fallen back so his hair and face were drenched. I thought, this was how he would look if he cried.

Dad called my name again but he wasn’t looking at me. He was squinting at Li and his arms were moving mechanically, almost

like a soldier’s.

It didn’t occur to me to go forward to meet him. I felt as if I hadn’t moved in weeks, not that I couldn’t but there seemed

no need to. The act of breathing seemed enough. I might have been in the audience watching my father and Li in a movie.

“I got worried with the rain.” Dad was panting a little. “Are you all right?”

“She is all right,” said Li quietly. “How are you?”

My father didn’t answer, and now that he was with us he stopped looking at Li. He bent his legs until he reached my level.

He touched my sopping hair and shirt.

“You must be freezing.” His voice was a low, worried grumble. I shook my head. I felt perfectly warm. “It’s time to come home,

Mei Mei.”

“Mei Mei?” Li nodded approvingly.

We formed a triangle the way we were standing. Li was staring at my father, my father at me. I looked back and forth. Only

then did I realize that Dad might not know Li and I were friends. And then I remembered I was disobeying him by being here.

“I feel better,” I said.

But he didn’t sound angry. “Your mother will be back soon. She’ll be frantic if you’re gone.”

“How is Diana?” Li asked as if he were an old friend of the family’s.

My father and I both stared at him. From the beginning Li had asked me about my father, my brother and sister, but never mentioned

my mother. I’d decided he either didn’t know she existed or else thought of her as another white witch.

Again, Dad didn’t answer. He reached for my hand, then reeled me in, first the wrist, elbow, shoulders, until he had me clasped

in a hug that stopped my breathing. When he let go, his eyes were wet, and not from the rain.

“I’m okay, Dad.”

“Thank you,” he said.

“You are welcome, of course,” said Lao Li.

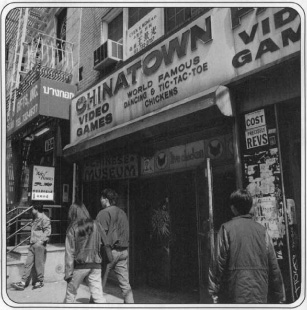

My father led me away. He didn’t ask what I was doing with Li, and he didn’t forbid me to see him again. But just a few months

later he sold his bottle cap patent. We left Chinatown within the year.

I

received this letter this morning.

Maibelle Love,

During afternoon darshan today I saw your face so clearly, heard your complaint, felt your sadness and anger, I decided the

Buddha wanted me to connect with you, and the Big D concurred. How I wish you would try a different path to the truth you

are seeking. Since I surrendered to the Dhawon I have been blessed by such light and acceptance. It has cleansed me of all

vile thought and confusion. Transformation is the way to enlightenment, Maibelle. You must step out of your past self as if

it were a suit of ill-fitting old clothes. Leave behind what happened. The Dhawon says there are too many bodies for this

planet, anyway, and too few of us fit to raise those already born. Children deserve joy and truth and harmonic bliss. If we

ourselves have not yet attained enlightenment, then we have no right to create new life. This is why I have followed the Dhawon’s

wisdom

and had myself sterilized. It is why you must not mourn or punish yourself for what is past. The new life you are creating

now is your own, Maibelle. You must die to rational thought, expectation, convention. Move beyond death to the wholly compassionate

welcoming grace of the Buddha, yourself, and the Universal Now.

Peace be with you.

Your loving sister,

Aneela Prem

My brother was no help at all.

“How

could

you?”

“Maibelle, calm. Breathe deeply. Transcend.”

“Cut the crap. Why Anna, of all people?”

“Darling, I never told a soul. Not that I can see what the big deal is. Now, if you’d

had

the kid—”

“You’re sure?”

“I told you. Not a soul.”

“That includes Mum and Dad?”

“No, they’ve got souls, at least last time I checked.”

“Asshole.”

“Atta girl.”

“No one?”

“No.”

I listened, weighing his silence as if it were a lie detector. He had Smokey Robinson on. “Tears of a Clown.”

I said, “Well. While we’re on the subject, you might think about getting that operation of yours reversed.”

“Do tell.”

“Anna’s had one, too. As it stands I’m this family’s last hope of succession.”

“Any prospects?”

“Not that I’d tell you. How’s Coralie.”

“I appreciate the confidence. Likewise, I’m sure. Don’t spend it all in one place.”

My brother’s wit won’t crack the code of my sister’s message. I want to believe it’s just cult babble, but there’s something

behind her words that unnerves me. Like a five-dollar fortune-teller who know things she can’t possibly know but refuses to

tell what they mean. This is my first letter from Anna since she stopped acknowledging birthdays as part of some spiritual

indoctrination ten years ago.

I would call her, but there are no phones at her ashram, and the nearest town is some twenty miles away.

It’s four in the morning, and I won’t sleep again tonight. I’ve just had a new dream about Johnny. It starts all right. We’re

lying together beneath a huge globe. His hands are outstretched, white and transparent, full of deep blue veins. I try to

touch him, but he leaps to his feet, starts running. I follow him over long green lawns toward a line of ocean. He slows to

a walk, but doesn’t stop at the shore. He walks on water.

“It’s okay,” he calls back over his shoulder. “Who needs China? Come on!”

He stops to wait for me, digs his toes into the ocean. He wears torn blue jeans and a white T-shirt, his hair a mop of light.

I run along the beach, looking for a way out to him. He continues on and I trail him. The waves lap at my feet. I sink into

sand. He keeps going, farther, farther out, and I keep after him, but now I feel someone’s breath against the back of my neck,

pressing forward, closer.

“Stay with me,” he calls. “Don’t look back! You can marry me in your dreams.”

I run until the breath from behind pours through me, burning my throat and crushing my chest. I let it pull me down. Johnny

sinks beyond the horizon.

Then unseen hands turn my head around to a face as white as eggshell, with straw hair and blackened teeth. Eyes that glitter

like jewels.

Henry’s basement bogeyman.

Dear Anna,

I appreciate your letter and the concern behind it, but I am confused. What, exactly, must I leave behind? What is all this

business about children? I am not angry. I really don’t know what you are talking about, so I’d appreciate an explanation

in clearer, more basic terms. There seems to be a lot I don’t remember these days, a lot I am trying to understand.

I’m sorry we argued when you were here. I miss you, Anna.

Your sister,

Maibelle

There have been no further chopsticks lessons, no more parties, though I have seen Tai’s friends in the street and they always

greet me by name and stop for a casual chat. Once when I was walking alone back to my apartment, I saw Lin Cheng outside Dean

and Deluca on Prince Street. I thanked her again for the sumptuous feast, apologized for taking so long with her book jacket

photograph. “Oh, you are welcome,” she answered. “Any friend of Tai’s is friend of ours. I was just joking about the picture,

anyway. I don’t really need one.” She meant it kindly, but the underlying statement hurt. In my own mind I still have not

passed the point of needing a house key, a mission, a sponsor to gain entrance. If I tried to go back alone, I’d again feel

eyes burning like switchblades into the small of my back.