Faces in the Crowd (18 page)

Coffee House also receives support from: several anonymous donors; Suzanne Allen; Elmer L. and Eleanor J. Andersen Foundation; Mary & David Anderson Family Foundation; Around Town Agency; Patricia Beithon; Bill Berkson; the E. Thomas Binger and Rebecca Rand Fund of the Minneapolis Foundation; the Patrick and Aimee Butler Family Foundation; the Buuck Family Foundation; Claire Casey; Ruth Dayton; Dorsey & Whitney, LLP; Mary Ebert and Paul Stembler; Chris Fischbach and Katie Dublinski; Fredrikson & Byron, P.A.; Katharine Freeman; Sally French; Anselm Hollo and Jane Dalrymple-Hollo; Jeffrey Hom; Carl and Heidi Horsch; Alex and Ada Katz; Stephen and Isabel Keating; Kenneth Kahn; the Kenneth Koch Literary Estate; the Lenfestey Family Foundation; Carol and Aaron Mack; George Mack; Mary McDermid; Sjur Midness and Briar Andresen; the Nash Foundation; Peter and Jennifer Nelson; the Rehael Fund of the Minneapolis Foundation; Schwegman, Lundberg & Woessner, P.A.; Kiki Smith; Jeffrey Sugerman and Sarah Schultz; Nan Swid; Patricia Tilton; the Archie D. & Bertha H. Walker Foundation; Stu Wilson and Mel Barker; the Woessner Freeman Family Foundation; Margaret and Angus Wurtele; and many other generous individual donors.

To you and our many readers across the country, we send our thanks for your continuing support.

MANIFESTO À VELO

An essay from

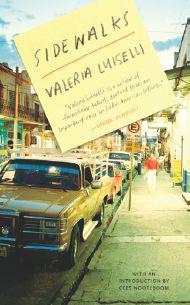

Sidewalks

by Valeria Luiselli

Paper • 978-1-56689-356-5

eBook • 978-1-56689-357-2

Stop

Apologists for walking have elevated ambulation to the height of an activity with literary overtones. From the Peripatetic philosophers to the modern flâneurs, the leisurely stroll has been conceived as a poetics of thought, a preamble to writing, a space for consultation with the muses. It is perhaps true that in other times the greatest risk one ran on going out for a walk was, as Rousseau related in one of his

Meditations,

to be knocked down by a dog. But the reality is that, nowadays, the pedestrian can’t venture out into the street with the same extravagant spirit and modernist love for the metropolis as the eclectic Swiss writer Robert Walser professed at the beginning of his novel

The Walk:

“One morning, as the desire to walk came over me, I put my hat on my head, left my writing room, or room of phantoms, and ran down the stairs to hurry out into the street.”

The urban walker has to march to the rhythm of the city in which he finds himself and demonstrate the same single-minded purpose as other pedestrians. Any modulation of his pace makes him the object of suspicion. The person who walks too slowly could be plotting a crime or—even worse—might be a tourist. Except for those who still take their dogs for a walk, children coming home from school, the very old, or itinerant street vendors, no one in the city has the right to slow, aimless walking. At the other extreme, anyone who runs without wearing the obligatory sports attire could be fleeing justice, or suffering some sort of noteworthy panic attack.

Speed cameras

The cyclist, on the other hand, is sufficiently invisible to achieve what the pedestrian cannot: traveling in solitude and abandoning himself to the sweet flow of his thoughts. The bicycle is halfway between the shoe and the car, and its hybrid nature sets its rider on the margins of all possible surveillance. Its lightness allows the rider to sail past pedestrian eyes and be overlooked by motorized travelers. The cyclist, thus, possesses an extraordinary freedom: he is invisible. The only declared enemy of the cyclist is the dog, an animal obscenely programmed to chase any object that moves faster than itself.

No dogs

If dogs tend to resemble their masters, the similarity is even more pronounced for bicycles and their riders. A bicycle can be found for every temperament: there are melancholy, enterprising, executive, fearsome, nostalgic, practical, nimble, and parsimonious bikes

Speed limit:

160

km/h

Julio Torri—a self-proclaimed admirer of urban cycling, who wrote a defence of the bicycle in the early 1900s—once pointed out that neither the plane nor the car is proportionate to man since their speed exceeds his needs. The same is not true of the bicycle. The cyclist chooses the speed that best fits the rhythms of his body, which, in turn, depend on nothing more than his own limitations.

The bicycle is not only noble in relation to body rhythms: it is also generous to thought. For anyone with a tendency to digress, the sinuous company of the handlebars is perfect. When ideas are gliding smoothly along in straight lines, the two wheels of the bicycle carry both rider and ideas in tandem. And when some stray thought afflicts the cyclist and blocks the natural flow of his mind, he only has to find a good steep slope and let gravity and the wind work their redemptive alchemy.

Pedestrian crossing

If, in the past, strolling was emblematic of the thinker, and while there may be places where it’s still possible to walk about deep in thought, this has little relevance to the inhabitants of most cities nowadays. The urban pedestrian carries the city on his shoulders and is so immersed in the maelstrom that he can’t see anything except what is immediately in front of him. Moreover, those who use public transport are restricted to a seat’s-worth of privacy and a few meters of visual range. And the motorist, who travels vacuum-packed in his car, unable to hear or smell or see or really exist in the city, is no exception: his soul is blunted at every traffic light, his gaze is the slave of the spectacular hoardings, and the mysterious, anarchic laws of the traffic set the standard for the variations of his mood.

For Salvador Novo, poet and cofounder of the modernist magazine

Los Contemporáneos,

“the step-by-step matching of our internal rhythms—circulation, respiration—to the deliberate universal rhythms that surround, lull, rock, yoke us, is renounced when we set off in an automobile, at an insane speed, to simply cancel out distances, change locations, swallow up miles.” The cyclist, in contrast to the person traveling by car, achieves that lulling, unworried speed that frees thought and allows it to go along a piacere. Skimming along on two wheels, the rider finds just the right pace for observing the city and being at once its accomplice and its witness.

Speed bumps

Of course, the bicycle can be used for other ends besides mere carefree travel: there are delivery men, cycle rickshaw drivers, and even bicycle knife grinders, a species now almost extinct. Not to mention that semialien life form: racing cyclists, sheathed to resemble undernourished scuba divers, sticking their tiny tight asses out as they speed through the city. But in spite of these riders who prize the utility of two wheels above its art, riding a bicycle is one of the few street activities that can still be thought of as an end in itself. The person who distinguishes himself from that purposeful crowd by conceiving it as such should be called a cycleur. And that person—who has discovered cycling to be an occupation with no interest in ultimate outcomes—knows he possesses a strange freedom that can only be compared with that of thinking or writing.

Keep your distance

The difference between flying in an airplane, walking, and riding a bicycle is the same as that between looking through a telescope, a microscope, and a movie camera. Each allows for a particular way of seeing. From an airplane, the world is a distant representation of itself. On two legs, we are condemned to a plethora of microscopic detail. But the person suspended over two wheels, a meter above the ground, can see things as if through the lens of a movie camera: he can linger on minutiae and choose to pass over what is unnecessary.

Go

Nowadays, only someone sensible enough to own a bicycle can claim to possess an extravagantly free spirit when he puts on a hat, leaves the writing room, or “room of phantoms,” and runs down the stairs to unchain his bicycle and ride out into the street.