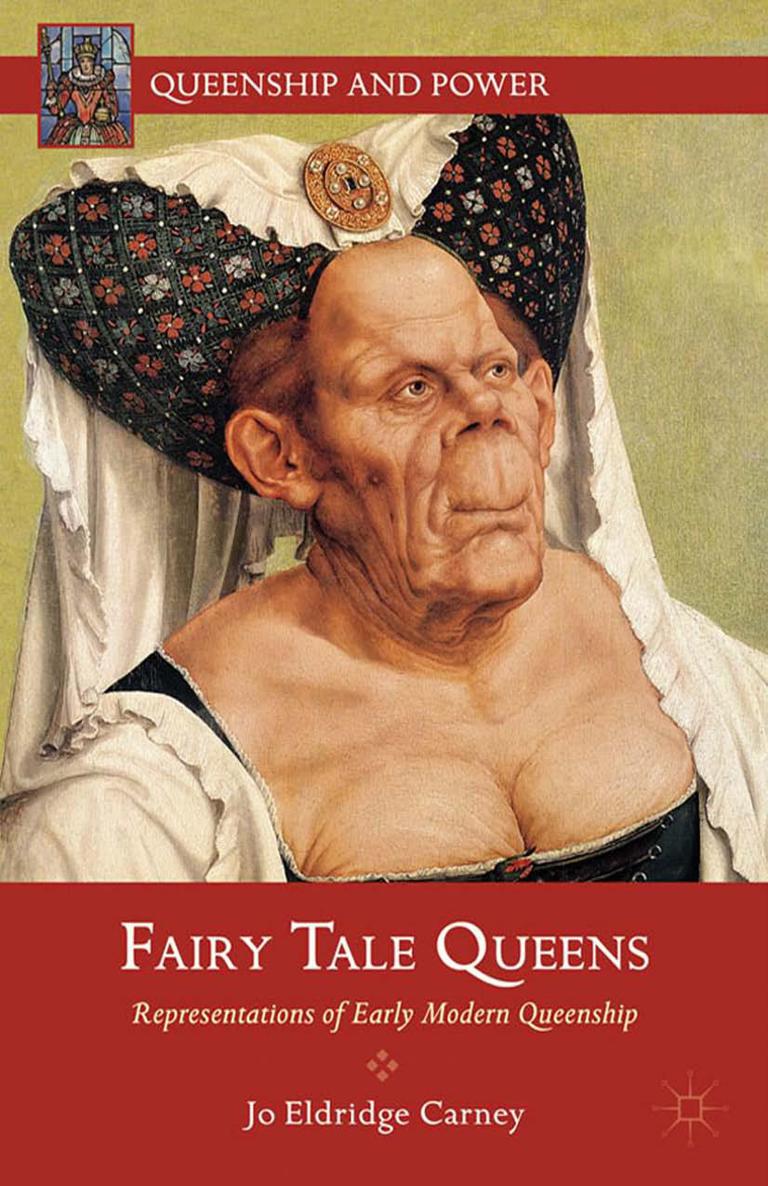

Fairy Tale Queens: Representations of Early Modern Queenship

Read Fairy Tale Queens: Representations of Early Modern Queenship Online

Authors: Jo Eldridge Carney

Tags: #History, #Europe, #England/Great Britain, #Legends/Myths/Tales, #Royalty

FAIRY TALE QUEENS

Representations of Early Modern Queenship

Jo Eldridge Carney

Palgrave Macmillan

October 2012

Copyright © Jo Eldridge Carney

All rights reserved.

First published in 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

ISBN: 978–1–137–26968–3

Printed in the United States of America.

QUEENSHIP AND POWER SERIES

Editors: Carole Levin and Charles Beem

This series brings together monographs and edited volumes from scholars specializing in gender analysis, women’s studies, literary interpretation, and cultural, political, constitutional, and diplomatic history. It aims to broaden our understanding of the strategies that queens—both consorts and regnants, as well as female regents—pursued in order to wield political power within the structures of male-dominant societies. In addition to works describing European queenship, it also includes books on queenship as it appeared in other parts of the world, such as East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Islamic civilization.

For a Fairy Tale Three:

Carole

Catie

Laurie

CONTENTS

1 Early Modern Queens and the Intersection of

Fairy Tales and Fact

2 The Queen’s (In)Fertile Body and the Body Politic

3 Maternal Monstrosities: Queens and the Reproduction

of Heirs and Errors

4 Men, Women, and Beasts: Elizabeth I

and Beastly Bridegrooms

5 The Fairest of Them All: Queenship and Beauty

6 The Queen’s Wardrobe: Dressing the Part

7 The Queen’s Body: Promiscuity at Court

ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Portrait of Queen Catherine of Aragon

3 Portrait of Christina of Denmark

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to The College of New Jersey for providing a sabbatical grant and released time to work on this project and especially for the support and encouragement of department chair David Blake; many thanks also to office managers Paulette Labar and Cecilia Colbeth and to Dean Ben Rifkin. To the many students who have shared in conversation about early modern fairy tales in the classroom and beyond, thank you. The librarians and the resources at The College of New Jersey and Princeton University Library were enormously helpful.

I am lucky that many friends have understood my passion for literary fairy tales, oddities, and early modern history, especially Suzanna Scott Curtis, Enrico Bruno, Courtney Eldridge, Brigitte Gebert, Melissa Hoffmann, Sarah Jablonski, Amy Mahler, and John Silver.

To beasts of burden Cappy and Sal for their unconditional love and to donkey-friends Lula and Satchel for their fairy-tale gold-producing properties and early morning calls, thank you.

And thank you to my husband and children, who teach me every day what hard work really is and what it means to “keep going.”

Thank you to “Queenship and Power” editors Carole Levin and Charles Beem for overseeing this series, which has produced so many inspiring works, many of which have contributed to this book. I also appreciate the patience, advice, and support of Chris Chappell and Sarah Whalen at Palgrave.

I am especially indebted to my extraordinary friend of many years, Laurie Curtis, whose countless acts of kindness and wise counsel make everything possible and who has also spread a good deal of her own fairy-tale love and knowledge. I am also grateful to my magical friend and colleague, Catie Rosemurgy, who indulged my excitement about strange discoveries and always asked helpful and clarifying questions.

For this project and so much more I want to thank Carole Levin for encouraging my ideas and offering so many helpful suggestions along the way. Carole’s exemplary work on Elizabeth I and on all things early modern has enriched the field immeasurably. Equally impressive is Carole’s tireless and unparalleled support of other scholars and students; so many of us have been the fortunate recipients of her careful nurturing and generosity. For 30 years of treasured friendship that have resulted in such a happy mix of work and play, thank you.

CHAPTER 1

EARLY MODERN QUEENS AND THE INTERSECTION OF FAIRY TALES AND FACT

A mid-sixteenth-century tale describes a powerful, conniving queen who sends a scented apple to a rival prince. The prince’s vigilant servant, suspicious of the gift, first feeds a piece of the fruit to his dog. Within moments, the dog drops dead. This time, the queen’s attempt to kill her enemy with a poisoned apple was foiled.

Such is the stuff of which fairy tales are made, but in fact this is a story that circulated about French queen Catherine de Médicis’ attempt to eliminate one of her many political enemies, Huguenot leader Louis de Condé.

1

The story may be apocryphal, but it points to an overlap between the annals of history and the fairy-tale genre. This intersection may seem incongruous if we view history as a chronicle of the factual, verifiable, and temporally specific and fairy tales as fictional, fantastic, and timeless.

These assumptions represent popular and naïve misconceptions about both fields. Any notions of historical inquiry as objective were outmoded long before twentieth-century postmodernists challenged grand narratives and monolithic worldviews. Historians must constantly revisit and reinterpret the “facts” before them; their enterprise is to discover and record information but also to interrogate, contextualize, and acknowledge multiple and contradictory perspectives. On the other hand, fairy tales, believed to be the antithesis of realism, can reveal local and historically specific truths about particular societies and peoples. Where verisimilitude and the marvelous converge in fairy tales, historical and cultural fault lines are often exposed.

This study takes as its departure point a connection between early modern history and fairy tales, focusing on the representation of queens, whose omnipresence in the genre has become one of its defining features. The relationship between fairy-tale queens and historical queens from approximately 1500 to 1700 is particularly relevant, given that this period witnessed both the development and proliferation of the literary fairy tale and the profound influence of queenship in the political landscapes of early modern England and Europe. The last few decades have seen a surge in scholarship both on fairy tales and on early modern queens, but there is no extensive analysis on their intersection.

Recent fairy-tale studies range from the earliest manifestations of tales in the classical canon to postmodern adaptations and reiterations. The works of Christina Bacchilega, Stephen Benson, Ruth Bottigheimer, Nancy Canepa, Donald Haase, Elizabeth Harries, Lewis Seifert, Maria Tatar, Marina Warner, and Jack Zipes, among others, have made critical advances in legitimizing a field of scholarship well beyond the boundaries of children’s literature.

2

Although these scholars employ a rich array of theoretical lenses—structural, feminist, linguistic, psychological, postmodern, and combinations thereof—most acknowledge, implicitly or explicitly, the historical specificity of fairy tales.

In their search for commonalities and shared organizing principles in the fairy-tale canon, folklorists and structuralists in the early and mid-twentieth century minimized the historicity of the tales. Max Lüthi’s theory of fairy-tale characters, for example, emphasizes their “one-dimensionality” and “depthlessness”: “figures without substance, without inner life, without an environment; they lack any relation to past and future, to time altogether...they lack the experience of time.”

3

Lüthi makes valuable observations about the abstract nature of the fairy-tale plot and characters, but abstraction need not be incompatible with historical import. Jack Zipes, whose extensive scholarship on fairy tales exposes the power relationships embedded in the genre, claims that fairy tales often “presented the stark realities of power politics without disguising the violence and brutality of everyday life” and depicted “conditions that were so overwhelming that they demanded symbolic abstraction.”

4

In other words, “symbolic abstraction” does not necessarily negate allusions to realistic subject matter; rather, it can provide an alternative mode of accommodation and representation. Zipes argues that early modern fairy tales’ preoccupation with “the concerns of the educated and ruling classes of late feudal and early capitalist societies” belies any argument that the tales are timeless and apolitical: “The fairy tales we have come to revere as classical are not ageless, universal, and beautiful in and of themselves...they are historical prescriptions, internalized, potent, explosive.”

5

Not only are the stories prescriptions in suggesting how life might be lived, as Zipes suggests, but they are also descriptions, offering us signals and clues that illuminate particular historical moments.

Ruth Bottigheimer also argues for the reciprocal relationship between sociopolitical concerns and the literary fairy tale: “Social history and literary genres exist in an intimate relationship with each other in every age.”

6

Thus, Bottigheimer claims, Giovanni Straparola’s tales emerged “in direct response to educational, social, economic, and legal forces” of mid-sixteenth-century Venice, whereas the Brothers Grimm revised and compiled tales within the context of the early nineteenth-century Napoleonic invasion and the incursion of French influence on German national identity.

7

Robert Darnton, Patricia Hannon, Lewis Seifert, and Maria Tatar, among many others, have also drawn important connections between fairy tales and their specific historical and ideological contexts.

8

One of the most contentious debates in current fairy-tale scholarship focuses on the relationship between the oral and print traditions of the genre.

9

Earlier scholarship promulgated a romanticized view of the fairy tale emerging from an oral and preliterate peasant tradition until post-Gutenberg authors managed to record the stories, but this is, as Elizabeth Harries puts it, a fairy tale about fairy tales.

10

More sophisticated and thorough scholarship on publishing history and canon formation has demonstrated that the evolution of the fairy tale was an overwhelmingly literary enterprise. Whereas this does not preclude the existence and influence of oral fairy tales, the focus of this study is on the literary tale, specifically the seminal works of the early modern period: tales published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by Giovanni Straparola, Giambattista Basile, and the French salon writers, including Charles Perrault, Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, Catherine Bernard, Henriette de Murat, and Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier.

Straparola, whose pseudonymous name means “loquacious one,” was the first European writer to mix fairy tales alongside his Boccaccio-inspired novelle. He published his two-volume collection

Le piacevoli notti

(

The Pleasant Nights

) in Venice in 1550 and 1553. The tales were subsequently reprinted several times in Italian and French translations; individual tales migrated to England and appeared in William Painter’s 1579 compendium, the

Palace of Pleasure.

11

Several decades after Straparola, another Italian writer, Giambattista Basile, became the first to produce a collection that entirely comprised fairy tales. Basile was a court official and poet from Naples and his

Lo cunto de li cunti (The Tale of Tales

), also known as the

Pentamerone,

was most likely written in the 1620s and was published posthumously around 1634. Basile’s stories, much more exuberant and off-color than Straparola’s, were composed in a Neopolitan dialect, perhaps to escape the attention of the censorious Church’s Index of Prohibited Books. Nonetheless, the

Pentamerone

was translated into Italian and French in the seventeenth century and went through several reprintings.

12

Straparola’s stories were known by Basile, and both writers’ works were in turn appropriated and reworked by a group of French writers at the end of the 1600s who initiated a fairy-tale craze that lasted several decades. Charles Perrault is still the most familiar name associated with the seventeenth-century French fairy tale; his

Histoires ou

contes du temps passé

(Stories from Past Times) (1697) includes many of the stories that have become the genre’s most well-known tale types: “Sleeping Beauty,” “Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Puss in Boots,” and “Bluebeard.” However, the figure even more responsible for the French fairy-tale vogue was Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, who coined the phrase

conte de fée

(fairy tale), a term that has endured in spite of the fact that fairies are not present in many of the tales in the canon. Madame d’Aulnoy first incorporated a fairy tale into her novel

L’histoire d’Hipolyte, comte de Douglas

(The Story of the Count of Douglas) (1690) and went on to publish several more volumes of fairy tales between 1697 and 1698. D’Aulnoy also hosted a vibrant salon for the glitterati in which fairy-tale readings and performances figured colorfully in the literary entertainment. Perrault and several women writers became part of the salon circle and many

conteuses

(female storytellers)

,

most notably Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier, Henriette de Murat, and Charlotte-Rose de la Force, published their own fairy tales in collections or miscellanies.

13

The fairy tale tradition carried on with the didactic tales of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in the mid-eighteenth century and the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen’s increasingly child-directed tales in the nineteenth century, but the parameters of our focus are the literary fairy tales published from approximately 1550 to 1700. Although most of our fairy-tale capital today comes from the popular tales of Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, and Andersen, this study hopes to encourage readers to explore the marvelous tales of the lesser-known authors whose works significantly enrich and expand our notion of the canon.

14