Falcon (11 page)

the left represents temporal things, the right everything that is eternal. On the left sit those who rule over tempo- ral things; all those who in the depths of their hearts desire eternal things fly to the right. There the hawk will catch the dove; that is, he who turns towards the good will receive the grace of the Holy Spirit.

10The trailing leg-straps by which the falconer holds the falcon are called

sabq

in Arabic, and are made of plaited silk or cord. Their Western equivalents,

jesses

, are made of soft leather. At home their ends are attached to a metal swivel to stop them

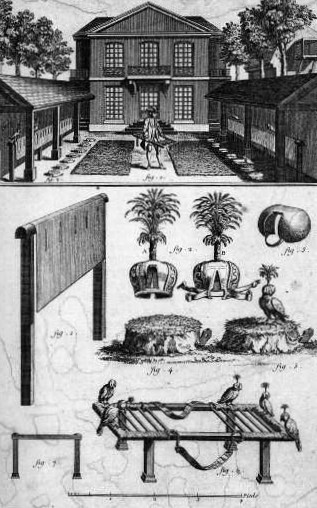

A plate from Diderot and d’Alembert’s 1751

Encyclopédie

showing the mews (above) and falconry equipment (below): a screenperch, two Dutch hoods, a rufter hood, turf blocks and a cadge for carrying falcons into the field.

In the United Arab Emirates, falconer Khameez calms a young falcon in training as he picks it up from its

wakr

,or perch.

twisting, and the swivel in turn to a leash. This leash is tied to a perch or

block

using the falconer’s knot – for obvious reasons easily tied and untied with one hand.

For centuries, small silver or brass bells attached to the fal- con’s legs or tail have been used to locate the falcon while out hawking, their plangent tones audible for half a mile or more downwind. In the 1970s American falconer-engineers devel- oped a tiny radio transmitter that could be attached to a falcon’s tail or leg. With a range of scores of miles, telemetry systems have dramatically reduced the possibility of losing a fal- con. Telemetry was greeted with enthusiasm by falconers in the Gulf States, for whom falconry continues to be a vibrant and popular cultural practice. Conversely, many European falconers viewed this new invention with distaste. A minority pursuit compared to more modern hunting methods, European falcon- ers have tended to validate and define falconry in terms of its rich cultural tradition and long history. They commonly assert

historical precedent as a legitimating device, and threats to its established, traditional modes of practice tend to be perceived as a threat to falconry itself. Yet these anti-modernist misgiv- ings seem to have been largely overcome. Today many falcons are flown with a modern radio transmitter attached almost invisibly to the tail – often right next to a Lahore brass bell, manufactured in Pakistan to a design of immense antiquity.

Plus ça change

.training falcons

The falconer’s first impression of a new falcon, sitting hooded on her perch, is one of unalloyed wildness. The slightest touch or sound and she’ll puff out her feathers and hiss like a snake. Falcons are trained entirely through positive reinforcement. They must never be punished; as solitary creatures, they fail to understand hierarchical dominance relations familiar to social creatures such as dogs or horses. As Lord Tweedsmuir wrote in the 1950s, secure in his impression that falcons were an avian aristocracy:

No hawk regards you as a master. At the best, they regard you as an ally, who will provide for them and care for them and introduce them to some good hunting. You only have to look at the proud, imperious face of a peregrine falcon to realise that. In reality you become their slave.

11Despite Tweedsmuir’s characterization of the falcon as a death-dealing dominatrix, falcons can become rather affection- ate. In the Gulf States, some falcons jump from their indoor perches and run to the falconer should he call their names. British falconer and author Philip Glasier had a tiercel peregrine

This 1430s water- colour drawing by Pisanello shows a young falcon wearing a brace- less hood and extra-large hack bells

that slept on his bookshelf and jumped onto his bed in the morning to wake him by nibbling his ear; another British fal- coner, Frank Illingworth, had a peregrine that took rides around the garden on the back of his dog; gyrfalcons enjoy play- ing with tennis balls and footballs.

So how does one train a falcon? Early modern authors cap- ture the key perfectly. Through the falconer’s constant attention to the bird’s ‘stomacke’: that is, her appetite and physical con- dition. Indeed, in the most basic sense, falcons are trained through their stomachs – through associating the falconer with food. If a falcon isn’t hungry, is

too high

, she’ll see little point either in chasing quarry or returning to the falconer. Con- versely, should she be a little

too

thin, or

low

in condition, she’ll lack the energy to give that palpable sense of inner urgency in flight that is the watchword of truly exciting falconry. The con- ditioning of a falcon revolves around a terrifying number ofvariables: the weather, the time of year, the stage in training, the type of food the falcon has eaten and how much exercise she has had. Falconers assess condition in a variety of ways. Some are quantitative: daily weighing, for example. Others involve tacit knowledges built from years of experience: feeling the amount of muscle around a falcon’s breastbone, the bird’s posture and demeanour, the way she carries her feathers, even the expres- sion on her face.

Taming and training a falcon is a serious and skilled busi- ness. Every autumn, falconers bring new falcons to their sheikhs and princes in the Gulf States. In long meetings, the quality and condition of each falcon are assessed, appraised and measured with fine exactitude. Falcons are tamed rapidly in this falconry culture; they are kept constantly on their falconer’s fist, or on perches nearby, totally immersed in everyday human life. While initially stressful, this method quickly promotes an unflappable tameness in the falcon. A similar method, termed ‘waking’, was commonplace in early modern Europe: the new falcon was kept constantly on someone’s fist until it overcame its fears sufficiently to sleep.

Western falcon training today is a far slower process. The untamed falcon is initially handled only while the falconer offers her food on the fist. Soon she associates the falconer with food and jumps to the fist from her perch. The distance she jumps for food is gradually extended and she soon flies to the falconer – first on a light line known as a

creance

and then free. In both Arab and Western falconry, free-flying falcons are trained to return to a lure, but more creative methods of retriev- ing falcons have existed: falconer Roger Upton recounts a story from the days when the only lights in the Saudi desert were campfires. Back then, one Bedouin falconer made sure he only ever fed his falcon right next to the fire. When this falconHighly ornate lures and hoods from the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian i

(

r

. 1493–1519).

became lost during hawking expeditions, she flew back, even at night, to the huge fire her anxious falconer built as a beacon for her return. Every spring he released her in the Hejaz mountains so she could breed, and every October he returned to the moun- tains, built a big fire and re-trapped her.

‘nothing so frequent’

For more than 500 years, falconry was immensely popular across Europe, Asia and the Arab world. It carried enormous cultural capital. Historian Robin Oggins describes early modern European falconry as an almost perfect example of conspicuous

consumption; ‘expensive, time consuming and useless, and in all three respects [serving] to set its practitioners apart as a class’.

12

Expensive it was. Extraordinarily so. In thirteenth- century England a falcon could cost as much as half the yearly income of a knight. Four hundred years later, Robert Burton maintained that there was ‘nothing so frequent’ as falconry, that ‘he is nobody, that in the season hath not a hawk on his fist. A great art, and many books written on it.’

13

Some European gentlemen hawked every day, even on campaign or when conducting official business. King Henry viii hawked both morning and afternoon if the weather was fine, and would have drowned in a bog while out hawking had his fal- coner not pulled him out. Medieval Spanish falconer Pero López de Ayala considered falconry an essential part of a princely education, for it prevented sickness and damnation and demanded patience, endurance and skill. For much of its long European history, falconry was considered to exemplify youth and the active life, and, like all elite pursuits, it was ripe for satire. In his 1517 work

De Fructu qui ex doctrina percipitur

, the Tudor diplomat and man of letters Richard Pace put these words into the mouth of a nobleman: ‘It becomes the sons of gentlemen to blow the horn nicely, to hunt skilfully and ele- gantly carry and train a hawk! But the study of letters should be left to the sons of rustics.’

14Despite falconry’s opposition to the

via contemplativa

, clergy were keen falconers too. D’Arcussia suggested that ‘more devout souls’ should go hawking in order to raise spirits ‘brought down from previous vigour by continual study or by having too many concerns’.

15

The councils of 506, 507 and 518 strictly forbade priests and bishops to practise falconry, but the clergy deliberately misinterpreted the word

devots

(devotees) so that the term would not apply to them. Pope Leo x was such an

Other books

Fay Weldon - Novel 23 by Rhode Island Blues (v1.1)

Landry 02 Pearl in the Mist by V. C. Andrews

Latham's Landing by Tara Fox Hall

They Call Me Crazy by Kelly Stone Gamble

How To Save A Life by Lauren K. McKellar

The Good Spy by Jeffrey Layton

Capture the Rainbow by Iris Johansen

The Book Club by Maureen Mullis

This Year You Write Your Novel by Walter Mosley

Pets: Bach's Story by Darla Phelps