Falcon (18 page)

And full-scale ecological catastrophes still occur, though they rarely make news in the West. Mongolia is the largest stronghold of the saker falcon. There, its populations wax and wane with the population cycles of voles. Because high vole

years denude steppe grassland, making life harder for nomadic herders, the Mongolian government has recently been treating vast areas of steppe with rodenticide. In 2001 the government air-dropped poisoned grain with a concentration of the rodenticide Bromdialone a hundred times higher than ther recommended levels. Bromdialone is prohibited for outdoor use in the us, the country that holds the patent. A drastic decline in the populations of sakers and other Mongolian rap- tors has consequently occurred.

Habitat loss, too, threatens falcon populations in many countries. With the collapse of collective farming, nomadic

A dead saker falcon at its nest in Mongolia, killed

by entanglement in artificial twine. Deaths of adult, breeding birds have a dispropor- tionate effect on falcon populations.

A saker falcon tail-feather.

herders no longer graze large areas of falcon habitat in Central Asia, and the resulting development of scrub and woodland on what was once grassland has reduced the populations of sus- liks, the saker’s main mammalian prey in some regions. Mongolian sakers have also suffered from the littering of steppe grassland with unbiodegradable plastic twine and rope; many nesting sakers are killed by becoming entangled in such materials. The fall of Communism and the opening up of vast tracts of Asian steppe have also brought serious problems for Saker populations in these regions in the form of organized gangs of falcon smugglers and the attentions of local people desperate to make money from the Arab falconry market. A terrible fragmentation and reduction in the range of this species has occurred; once found from Europe right across to China, saker populations have been split into two, and both grow smaller year by year.

A growing realization of the scale of this problem has led to the creation of falcon identity databases for tracing falcon movements throughout the Gulf States; many governments there are moving toward official agreements for the biologically sustainable harvest of wild falcons. Organizations such as the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency in the uae and the National Commission for Wildlife Research Conservation and Development in Saudi Arabia have been instrumental in shaping these policies. These organizations work on other problems associated with Arab falconry, such as the traditional falcon-trapping techniques in Pakistan that exert a heavy toll on lugger falcons, used as

barak

or decoy birds to trap peregrines and sakers. And they work too on the popu- lation ecology and conservation of that most traditional quarry of Arab falconry, the Houbara bustard, which is under intense pressure from falconry in much of its range.And while it is now illegal to kill falcons in much of the world, they are still shot, trapped and poisoned. In Britain, recent peregrine declines in Scotland, Northern Ireland and north Wales have been seen as due to direct persecution. Some gamekeepers, watching their grouse stocks dwindle, see falcons as directly challenging their livelihoods. Some racing-pigeon owners living near peregrine eyries despair of the toll on their flock: to them, falcons are genuinely malevolent killers. Both are baffled by the untouchable cultural status of the falcon. After all, corvids and foxes also kill grouse and pigeons, and they can be legally controlled. Even bird protection societies destroy them on their nature reserves. What makes a falcon dif- ferent from a crow or a fox? they ask. Such a question is baffling to bird conservationists whose idea of falcons as wildlife icons seems unshakeably and self-evidently true. And so conserva- tion discourse characterizes those who call for falcon control as either misguided or evil – and dialogue between the two sides becomes almost impossible. Certainly the story is an unhappy one, and the questions it raises about the battles over owner- ship of the meanings of nature are troubling for policy-makers, bird-lovers and falcons alike.

- Military Falcons

Compare and contrast the reasons why an eagle will aggressively defend its territory with the reasons why countries defend their national borders.

1

The knight-as- falcon, from an early

14

th-century manuscript.

A trained peregrine stands to attention on the ari8228 passive warning radar of a Blackburn Buccaneer. Poised on this power- ful low-level British nuclear bomber, she looks ready for flight. Head haloed within the curve of the open canopy, eyes scanning the far horizon for possible targets, the bird’s form irresistibly mirrors the plane – and she is a neat symbolic stand-in for the absent pilot: even her facial markings suggest a flight helmet. What is happening here? Is this merely one recent manifesta- tion of an association between falcons and warfare that spans centuries and cultures, a snapshot resolving itself from history? It might seem so. Russian ornithologist G. P. Dementiev described an ancient ‘oriental proverb’ that ‘falconry is the sister of war’.

2

Eighth-century Turkic warriors were thought to become gyrfalcons after they died in combat; Genghis Khan disguised his armies as hawking parties, and fifth-century Chinese falcons carried military messages tied to their tails. And falconry trained military men as well as birds: sixteenth- century Samurai manuals had a falconry section, and falconry was a component of the education of the medieval European knight. Thought to foster chivalric qualities and to hone tacti- cal skills for battle, similar virtues are still appealed to today: falconer and author Nick Fox suggests that the qualities of strategic thinking one develops as a falconer gives one the edge

in – one would hope less bloody – boardroom battles. The list continues: seventeenth-century English Royalists battled Parliamentarian troops with 2 lb Falcon cannons. Three cen- turies later the us Air Force named their guided quarter-kiloton nuclear-armed air-to-air missile the aim-26 Falcon

.

A 1946 American book catalogue described peregrine eggs as ‘atomic bombs’ – a heart-rendingly ironic metaphor, for those eggs were doubtless contaminated by pesticides as invisible and deadly as fallout.But this Buccaneer falcon is not a mascot. It is a live bird recapitulating the aircraft’s role

,

a bird literally weaponized. An integral part of British air defence systems, its task is to defend the aircraft by targeting its potential destroyers – gulls. Ever since the us built an airbase in the middle of an albatross colony on Midway Island in the 1940s, ornithology has been a branch of military science. A single bird sucked into a jet intake or flung through a canopy can destroy a plane as spectacularly as can anDefenders of the air: a female peregrine and a Blackburn Buccaneer.

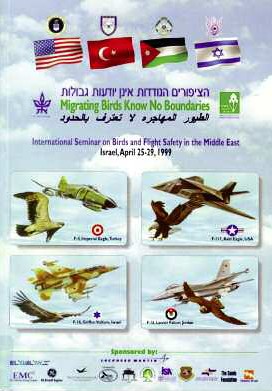

Raptors and air- craft are matched by nationality on the cover of this report. A lanner falcon and an

f-16

Fighting Falcon share Jordanian air- space.

air-to-air missile. On Midway the us Navy hit upon radical habi- tat management as a solution. They paved most of the island. Albatrosses don’t nest on concrete.

But the problem is not limited to the Pacific theatre: airfield grass everywhere attracts flocking birds such as starlings and gulls. Shooting them or scaring them with vehicles doesn’t clear a runway and its associated airspace in seconds: but falcons do. Enter the cavalry. The falcon on the Buccaneer is from a 1970s

Navy falconry unit stationed at Royal Naval Air Station Lossiemouth in Scotland. Initiated by falconer Philip Glasier, the team won its wings with a ‘live-fire’ demonstration to a group of officers, reporters and photographers. Clustering expectantly at the flightline, the naval officers were dubious. They were unconvinced that falcons could safely clear duty run- ways, and ‘did not fancy having a bunch of crazy falconers let loose on their airfield’.

3

But Glasier’s demonstration was flaw- less. Cast off at a flock of herring gulls sitting on the runway, the falcon made the gulls clear the horizon in seconds, all save for one luckless laggard she pulled from the sky.Today, similar airfield bird-clearance units operate world- wide. The media loves their glamour; for the public they are a ‘greener’, more acceptable bird-control method than shotguns. And the military loves them too, for falconry units powerfully naturalize the ideology of military airpower. The unspoken argu- ment runs as follows: if the military can demonstrate that natural falcon behaviour is the biological equivalent of tactical air war- fare, then who can possibly see air warfare as wrong? It’s

natural

. This is a crafty move, and we buy into it wholesale. If we didn’t, that peregrine sitting on the Buccaneer would look incongruous. The naturalization works in part because war and nature are tra- ditionally assumed to be utterly separate realms. ‘War’, wrote Karl von Clausewitz, ‘is a form of

human

intercourse.’

4

But the strange history of military falcons shows, by turns bewilderingly, amusingly and horrifyingly, that the traditional supposition that war and nature are utterly separate realms is a lie.Keep us interventionist foreign policy in mind when read- ing the words of a bird-clearance contractor at March Air Reserve Base, California. ‘Wherever the falcons fly, that area becomes their territory’, he explained in

Citizen Airman

maga- zine in 1996. ‘In the bird kingdom’, he continued, ‘boundariesare taken very seriously. It’s life or death.’

5

Troubling. For these falcons are

not

behaving territorially, of course. They are not protecting their territory from intruders. They are

hunting

. What’s more, these confusions point to something about the nature of science, for the concept of bird territory itself has a military history. It was first described by British ornithologist Eliot Howard just after the First World War had decisively established the bloody realities of international territoriality on a grand scale. And in a rather less subtle naturalization of tactical air warfare in the late 1990s, the owner of the bird- clearance project at March Air Reserve Base explained earnestly that ‘just as the us puts an aircraft carrier off Iraq and flies fighter sorties to establish airspace dominance, our falcons do the same thing’.

6But how is it the same? Is a falcon a fighter jet? Both are con- ceived of as pushing the outside of the envelope of physical possibility; both are often considered perfectly evolved objects in which form and function mesh so precisely that there is no room for redundancy. The falcon has long been the embodied shape of aviation’s dreams of the future. Back in the 1920s, Pennsylvania falconer Morgan Berthrong recalls an aviation engineer admiring a trained peregrine above, her wings pulled back into a sharp delta shape as she glided into a stiff headwind. ‘See that silhouette?’ exclaimed the engineer. ‘When we develop a motor strong enough,

that

will be the shape of an airplane.’

7

And yes, General Dynamics’ f-16 ‘Fighting Falcon’ was named after the bird, and there are stories that the aeronautical engi- neers put peregrines through their paces in wind tunnels while designing the plane. Such tales may be apocryphal, but their continuance bespeaks an urge to show the plane as a more- than-material object whose function and form are as highly evolved as that of its natural exemplar, the falcon. ‘If it looksright, it flies right’, runs the test pilots’ dictum. And war-bird homologies have been loaded with serious ideological weight. Kansas-based organization ‘Intelligent Design’ uses the plane- peregrine example to support the theory that intelligent causes are responsible for the origin of life and the universe.

mobilizing falcons

But twentieth-century falcons have been tasked with military roles far beyond airfield clearance or martial symbolism. The Second World War mobilized falcons too; and they flew for both sides. Allied planes carried a box of homing pigeons to be released if they were shot down behind enemy lines. There was a problem, however: wild English peregrines were catching and eating the pigeons after they’d crossed the Channel. Alarmed, the Air Ministry ordered that these quisling falcons on the south coast should be destroyed. Between 1940 and 1946, around 600 were shot, many eggs broken and young killed. Yet, at the same time, Allied peregrines were ‘signed up’. Falconer Ronald Stevens was convinced that falcons could be used in the war – somehow. He’d heard that in 1870 trained German fal- cons had been used to intercept the French Pigeon Post in the siege of Paris. Stevens quickly set to work. With a friend, he built a miniature range. ‘On it’, he explained, ‘we put a ring of falconers round a besieged city, we covered a salient, we put a “net” of falconers behind enemy lines and in fact disposed falconers in every way we could think of.’

8

Excited by the prospects, he sent photographs of the models, along with exten- sive logistical analyses, to the Air Ministry.Stevens must have been excessively persuasive, for a top- secret falcon squadron was recruited, trained and scrambled to patrol the skies above the Scilly Isles, near Keyhaven, and on the

east coast between 1941 and 1943. A biological addendum to the top-secret chain of Key Home radar stations ringing the coast- line, its mission was to intercept ‘enemy pigeons’ released from German e-boats or the like. An exclusive on the secret project later appeared in the American press. ‘Operations by friendly birds were controlled just like airplanes so they knew where every bird was all of the time’, it enthusiastically explained. ‘Falcons were taught to fly at great heights and to fly in circles like an aircraft on patrol duty . . . a falling trail of feathers meant another dead Nazi bird.’

9

What wasn’t revealed was that the practical results of the operation were almost nil. While many pigeons were killed and one or two captured alive, only two carried messages. An raf commander dryly related the fate of one pigeon pow – put to work ‘making British pigeons’ in a Ministry of Defence pigeon-loft. But successful or not, it didn’t really seem to matter. The peregrines kept flying. Officers from Intelligence, the Royal Corps of Signals and the Air Force fre- quented the unit to watch ‘thrilling’ demonstration flights, and ‘were most impressed with the hawks’ performance’.

10

Of course they were. Falcons were fast, manoeuvrable, their prey outflown, out-armed and despatched with a winning ‘clean- ness’, naturalizing the ideology of honourable combat. Falcons were a moral predator. In 1948 Frank Illingworth recalled a cliff- top peregrine-watching session. ‘Mock battles are best demonstrated by two wild peregrines in playful mood’, he wrote, before continuing:the profusion of winged movement which we watched that pre-war morning rivalled anything I saw in the same skies during the Battle of Britain . . . a few sharp wing- beats, a few chattering cries suggesting staccato machine-gun fire, and the tiercel ‘fell away’ like a black

Other books

Hired: Nanny Bride by Cara Colter

One or the Other by John McFetridge

The Splendour Falls by Susanna Kearsley

Wild in the Moment by Jennifer Greene

The Bone Box by Gregg Olsen

150 Vegan Favorites by Jay Solomon

Ronicky Doone's Treasure (1922) by Brand, Max

The Bunker (The Infected Series Book 2) by Gowland, Justin

In Her Eyes by Wesley Banks

Colder Than Ice by MacPherson, Helen