Falcon (17 page)

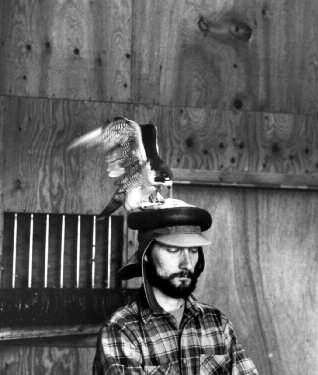

Sexually imprinted on humans, this tiercel peregrine

is copulating with a specially constructed hat. Beneath the hat is Peregrine Fund falcon breeder Cal Sandfort.

benevolent science

Scientist-conservationists such as Tom Cade and Richard Fyfe fascinated the media. Lacking falcon obsessions themselves, journalists and writers wondered what drove such people to save the peregrine. David Zimmerman attacked the question with high-psychological relish, assuming that individual endeavours to save animal species reflected a deep, personal desire for immortality. Saving a species is an ‘act of immortal salvation’, he explained; the ‘mortal who assists in this act . . .

transcends his own mortal being . . . here indeed is a potent human motive!’

23But the efforts of the Peregrine Fund and similar institutional projects could be seen as a salvation for science itself. In the new climate of the 1960s science was no longer routinely perceived as a progressive force for good, or as a disengaged, ideologically neutral intellectual pursuit. Public distrust of the scientific enterprise and its white-coated practitioners was at an all-time high. Cade and the Peregrine Fund were different. Cade was pre- sented in the media as a heroic figure, strong, caring, passionate and deeply moral. A new breed of scientist was uncovered to a world that had lost faith in the benevolence of institutional science. And these new scientists were heroes. The Peregrine Fund became bathed in the mythical light shared by Kennedy’s White House. ‘In retrospect’, Cade recently wrote of those early years, ‘I believe it was a kind of Camelot – a special place, at a special time, with very special people who were totally commit- ted to restoring the Peregrine in nature.’

24releasing falcons

These ‘very special people’ were nearly all falconers. And the thousands of years of what Cade called the ‘evolved technology’ of falconry provided a ready solution to the conundrum of how to release captive-bred falcons into the wild. The technique of

hacking

had been used for centuries to improve the flying skills of falcons taken as nestlings. Placed outdoors in an artificial eyrie known as a hackbox, they were fed and cared for by humans until they learned to fly and hunt like wild falcons, a process that might take many weeks, as D’Arcussia explained in the sixteenth century: ‘All May and a few days of June will have passed before the youngsters have learnt their lessons and can

After hatching in artificial incuba- tors, young falcons are hand- fed with minced quail for a few days before being returned to their parents. At this early stage they’re extremely delicate and need constant warmth.

take a perch, fly into the eye of the wind, and hang like lamps in the sky.’

25

At this point, the young falcons were trapped by the falconer and trained.Hacking seemed the perfect solution. The only difference between conservation hacking and falconry hacking was that in the former you failed to recapture the young. Where to site artificial eyries was the next question. The urge to repopulate historic east-coast cliff eyries was strong; geographical nostalgia entwined with conservation praxis. The young would become ‘imprinted’ on the eyrie, and thus might return once they were grown, perhaps to breed. Those who worked at the Peregrine Fund had seen falcons nesting at these very cliffs; they wanted to restore the ecological plenitude of vital local landscapes they’d seen destroyed in their own lifetimes. Hack-site atten- dant Tom Maechtle explained that his job gave him a deep understanding of the ‘ecology of the cliff. Falcons once com- pleted that ecology; when the falcons died, the cliffs were dead. To see young falcons flying from the old eyries is to see nature put right again.’

26However, the first major restocking experiments didn’t go quite as planned. Without the presence of aggressive adult birds to guard the young released at historic cliff eyries, recently

fledged birds were often killed by great horned owls as they slept. Five were killed in this way in 1977. ‘There’s not much we can do about owls except avoid them’, opined Cade.

27

Falcons hacked from eyries built on towers in untraditional sites were much more successful. Birds fledged successfully from towers in New Jersey’s salt marshes, and from a 75-foot-high ex-poison-gas shell testing tower on Carroll Island. These highly publicized releases went well. By the early 1980s the Peregrine Fund was releasing more than 100 peregrines a year, both in the eastern us, and, with the opening of a second facility in Colorado, to much of its former range in the West. The reintroduction schemes of the Peregrine Fund and other dedicated organiza- tions have succeeded to such an extent that the peregrine has returned to breed over much of its former American range; a landmark recovery in the history of conservation biology.how wild is a captive peregrine?

The release of these captive-bred falcons was, however, contro- versial. Was it right to release these birds into the wild? If the extinct east-coast

anatum

peregrines had been the last native fragments of a primeval past, what were these new birds? They had not evolved here. These were mongrel birds of mixed gen- etic and geographical origin, their parents hailing from as far afield as Scotland and Spain. They were not the falcons that had evolved over millennia in the eastern us. And how ‘wild’ were they? Surely, the distilled essence of wildness, by its very nature, should have been reared on rocks and cliffs. Is a peregrine less wild for having been incubated in forced-air machines, reared between walls?The debates over the provenance of the released peregrines illumine deep and divisive arguments about natural value that

A baby Peregrine Fund falcon and a crowd of fascinated Boy Scouts. Educating the public is a prime concern

of the Peregrine Fund and similar organizations.

course through conservation biology. One current in environ- mental philosophy values organisms or ecosystems through an appeal to their history. In this tradition, the intrinsic value of an animal or habitat is relative to the naturalness of the process by which it came to exist. No replanted prairie or rainforest is as valuable as one that naturally evolved, it contends. ‘Wild’ or ‘untouched’ ecosystems possess greater intrinsic value than those that have been affected by human activity. In this view, because they were

not

the natural inhabitants of the east-coast environment, these peregrines were a travesty; alien, ‘man- made’ birds. Better no peregrines than the wrong peregrines, their arguments ran.Cade and his congeners had no truck with this attitude. Their version of nature was dynamic, inclusive, and involved deeply emotional ties to bird and landscape that supplanted naïve nativist concerns. Not only, they argued, would these new

birds evolve to suit the new, less primeval landscapes of the east coast, but they also restored local historical and ecological con- tinuity. Full of peregrines, the rocky cliffs and the sheer blue skies above them would once again be ‘live’. Young Americans could once again watch the heart-stopping stoop of the pere- grine, as much a part of the American sublime as the Grand Canyon or Delicate Arch. As Cade movingly wrote of one released tiercel,

I tell you truly, I cannot

see

a difference with my eyes, nor do I

feel

a difference in my heart, which pounds against my chest with the same vicarious excitement when the Red Baron stoops over the New Jersey salt marshes, as it did in 1951 when I first saw this high-flying style of hunt- ing performed by the wilderness-inhabiting peregrines of Alaska.

28A young Peregrine falcon peers from its recently opened artificial nest, or hackbox. Great Horned Owls and Golden Eagles were often a danger at natural release sites like these.

Ultimately, Cade shows that in terms of function and aes- thetics, wild and captive-bred falcons admit no difference. Genetic and taxonomic distinctions fall in the face of the ani- mation of an entire landscape with the exhilarating flight of the falcon.

success for the falcon?

Exuberant celebrations attended the decision to de-list the peregrine from the us Endangered Species Act in 1999. Al Gore issued an statement praising the esa. ‘Today, more than 1,300 breeding pairs of peregrine falcon [

sic

] soar the skies of 41 states’ he enthused, ‘testament that we can protect and restore our environment even as we strengthen our economy and build a more liveable future.’

29

All was well; some ecological integrity had been restored; the peregrine had been saved. It was a conservation triumph. But the story is far from over. Chemical contaminants still threaten falcon populations. Researchers in Sweden, for example, find high levels of flame retardants such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (pbdes) in peregrine eggs. Moreover, the chemicals involved are often depressingly familiar. While legislation on pesticide use is tight across Europe and North America, agricultural chemical cor- porations have ready markets elsewhere. Pesticides have brought local extinction to lanner falcons in some African agri- cultural regions, and American peregrines that winter in South America and Mexico return to breed in the us with high dde levels.

Other books

Anabel Unraveled by Amanda Romine Lynch

Their Stolen Bride (Bridgewater Menage Series Book 7) by Vanessa Vale

Never Say Spy by Henders, Diane

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Mysterious Mr. Heath by Ariel Atwell

Dangerous Curves Ahead (BBW Erotic Romance) by Arabella Quinn

Beauty and the Beach by Diane Darcy

Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle by Russell McGilton

The Billionaire’s Handler by Jennifer Greene

Starfish Island by Brown, Deborah