Faldo/Norman (16 page)

Authors: Andy Farrell

Norman, in the meantime, had hit a nine-iron to 18 feet but had to wait so long for Faldo to play up that he ended up

three-putting for a bogey five. There was only one shot lost in the end for Faldo but he flew the green at the 4th with a three-iron and failed to get up and down so that was a bogey four, although Norman three-putted from 45 feet to also drop a shot. At the 3rd, thinking his first putt was uphill, Norman had blasted his birdie try eight feet past, so inexorably at the 4th he ended up five feet short. ‘From there on I had pretty good speed with my putts,’ he said. ‘The difficult part of putting today was judging the last two feet of break because the wind was going to roll the ball a little more than you anticipated.’ Norman was back to ten under par, Faldo was six under: the gap was still four.

By the turn, it was down to three, Faldo making an 18-foot putt at the 9th. On the back nine, however, Norman drew away again. At the 10th, Faldo, trying to hit a low seven-iron onto the raised green, pushed his approach and dropped a shot. Then came the 12th. Norman went with an eight-iron but caught a gust of wind and saw his ball land in Rae’s Creek, the water he had been lucky to avoid the previous day. He had made a fine up-and-down for a par on the Friday, and this time he again stayed calm, making a ‘good’ bogey. Giving himself the yardage he wanted with the drop, he hit a sand wedge from 81 yards to ten feet and holed the putt for a four.

Faldo had selected a seven-iron for his tee shot at the 155-yard hole but the wind had died down slightly when he came to hit and he went through the green. Instead of taking advantage of the Australian’s visit to the drink, the Englishman now had the more difficult second shot. He was on a downslope, with pine needles and seed pods behind the ball, playing over a small depression to an upslope, after which the green runs down towards the water Norman had just visited. ‘That sounds pretty tough to me. And it’s Augusta,’ Faldo said later in trying to convey the high tariff of the shot. He got it to around the same distance for par as Norman

had for bogey but, still miffed at having let go a chance of closing the gap with a tee shot on the green, he missed the putt.

Norman said: ‘When I hit the tee shot and it ended up in the water, I never got mad because I hit the shot solid. It would have been a different story if I had hit a bad shot. Then it would have been, “why did you make a stupid mistake like that?” But I put a good swing on it. It obviously got caught up in the wind. So you just take your medicine from there and make your four. When you do that type of stuff, it makes you feel good because you know you never hit a bad shot. You walk off with a bogey but it could have been worse.’

Asked why he selected the yardage he did for his third shot, Norman answered: ‘Because I’ve probably hit 50,000 golf balls from 81 yards and I know how to hit 81-yard shots. That’s the type of shot where you know you want to be certain to put a lot of juice on the ball. That green is very, very firm. That’s the reason I put it at that distance because it was a good three-quarter sand wedge shot.’ Alas, the following day when faced with a similar recovery, it did not work out quite so well.

Norman was asked if he had had a little luck during the round, such as at the 12th hole, to keep his lead intact. ‘I don’t think that is luck,’ he said. ‘I see that as the way the game is played. Luck is when you get a bounce off a tree and come back on the fairway [as he did at the 14th in the first round] or what happened at 12 yesterday [when his ball stayed on the bank]. That was a bit of luck.’

After a ‘half’ in bogeys at the 12th, both men completed Amen Corner with birdies at the par-five 13th. It might well have been a half in eagles as both hit big drives round the corner and then mid-irons close to the flag. Norman missed from ten feet, Faldo from eight feet – another chance lost, he felt. Another went at the 14th. Norman chipped and putted for a par from the back edge

but Faldo had a ten-footer for birdie which slipped by. Yet again, at the 15th, it was Faldo who seemed to be in a good position. Norman pulled his drive and had to lay up with a four-iron back to the fairway. Faldo hit a fine drive and then a four-iron onto the green but 60 feet right of the hole. While Norman got up and down with a pitch shot and putt from six feet for a birdie four, Faldo three-putted, missing again from inside ten feet.

The 15th had already seen plenty of drama in this third round as Jack Nicklaus eagled the hole, chipping in from beyond the bunker to the right of the green. Seve Ballesteros had a fright when his chip from behind the green ran down the bank into the pond at the front. He did not like that pond, having deposited a four-iron shot there when he lost to Nicklaus in 1986 and now, as he peered into the water to see if his ball was playable, a fish jumped out of the water and made him jump even higher. Colin Montgomerie, meanwhile, was not enjoying himself at all. One of the pre-tournament favourites, the Scot hit his third shot over the green, left his chip short on the fringe (fearing the fate of Ballesteros’s chip from earlier) and then four-putted for a triple-bogey eight. ‘This is the most frustrating place I’ve ever played,’ he wailed as he fell back to five over after three rounds.

At the short 16th, Faldo pushed a nine-iron into the bunker short-right of the green. He later ranked it as his worst shot of the week. It cost him a bogey as his par putt lipped out. Norman had hit a nine-iron to six feet and made the putt for a birdie so he had gained three shots in two holes. He was now seven ahead of Faldo.

Coming into the week, Faldo had been most confident with his putting and until this series of miscues it had served him well. Even with them, he was only a hair behind Corey Pavin at the top of the putting statistics for the first three rounds. ‘Play wasn’t

bad,’ Faldo said as he summed up his round. ‘I could have saved the day by making some of those putts on 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. I missed all of them, the longest being eight to ten feet.’

It was, in fact, at the next two holes that he saved the day as his putting came good. At the 17th, he hit a wedge to six feet and made that for his sixth birdie of the day. It not only reduced his arrears to six strokes but took him back to seven under par and one ahead of Mickelson in third place. Had he remained at six under, he would have shared second place with the left-hander. But because Mickelson had been playing ahead of him in the third round, under the ‘first-in, last-out’ rule, it would have been Mickelson playing with Norman in the final round. And how different might history have been?

Of course, Faldo still had to par the last and to do so he faced yet another ten-footer. It was the sort of overcast day where dusk closes in early but there was still enough light around. At the time, it is likely not many people watching realised the importance of Faldo’s putt. A lead of six shots or seven, surely Norman had enough of a cushion either way?

But Faldo recognised how important it was. It wasn’t that he thought if he could play alongside Norman on the final day he

would

win. But, at least, he

could

win. Or, at the very least, apply some pressure in a way that would not be possible if he were not in Norman’s eyeline the next day. Other players might have thought the opposite, that getting out ahead of Norman, away from the intensity of the final pairing, and posting a target that the Australian would have to chase would give them their best hope of causing an upset. Not Faldo. He wanted to be alongside Norman for another 18 holes. He made his par.

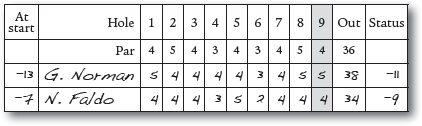

Norman’s third successive sub-par score, a 71 that felt even better given the conditions, put him at 13 under par on a total of 203. Only two players had ever been lower at the same stage of the Masters, Ray Floyd on 201 in 1976 and Nicklaus on 202 in 1965. More pertinently, the day’s battle with Faldo had been won, the Englishman had not been at his best and returned a 73 to be seven under par. To be fair to Norman, he was the last person to concede his conquest was in the bag. Faldo, hanging on for grim death as only he can, was admitting nothing.

After the round, with daylight fading fast, Faldo had little inclination for a lengthy debrief in the interview room. ‘I’m a long way back,’ he said. ‘But, you know, anything is possible. It’s all to gain and nothing to lose tomorrow. Just go out and play, and if it comes off, well, it will put a lot of pressure on him.’ Asked if he had a target score in mind for the next day, he said: ‘To shoot something good. Who knows? You shoot 66, 65, it could be something around there. It’s got to get me in the right direction.’ There was only one direction he was heading in at that moment – the range before the light totally went. ‘I need to go and practise, guys.’

Norman, who parred the last two holes, also wanted to practise after his round and ended up on the putting green well after darkness had fully descended. But first there was another long session in the interview room. He went through his round and tackled everything thrown at him from grim reminders of his past defeats to predicting the future, or at least the next 24 hours. Overall, he was happy with his 71. ‘That’s the equivalent of shooting in the 60s, I suppose. There wasn’t a lot of give in the golf course. I’m sure there’s not going to be a lot of give tomorrow, either.’

‘Do you feel as in control of the tournament as the leader-board would indicate?’ he was asked. ‘The best way for me to

answer that is I feel good within myself forgetting the golf tournament. That’s the only way I can approach it, in a very good philosophical sense in my mind. I’ve got another day to go and there’s 18 tough holes to play.’

‘Greg, is there an urge to be maybe a little more cautious tomorrow?’ ‘I’m just going out there as if nobody’s got a lead. We’re all at the same mark tomorrow, as far as I’m concerned, when we tee off. I’m just going to play the necessary shot I see to play at the time.’

‘Since you have a six-shot lead, why approach it like everybody’s tied?’ ‘That’s the way I approach it every day. Everybody’s even and if you beat the guys in your mind when you’re even with them, then you know you’re going to beat them.’

‘Greg, how excited are you right now?’ ‘I feel pretty good. Yeah, I’ve a lot to do, so there’s no point in getting excited now.’

‘Greg, if you win tomorrow, are you going to look back over the last couple of days as being the difference in the tournament?’ ‘Ask me that tomorrow.’

‘Is it fair to say you’re anticipating this round of golf more than any others you’ve played knowing the history of the Masters?’ ‘Sure. Irrespective of what happens, I’m going to enjoy every step I take. I’ve got a chance to win the Masters. I’ve been there before. There’s no better feeling than having a chance to win a major championship.’

Hole 9

Yards 435; Par 4

D

ON’T CALL

Greg Norman a ‘choker’. Someone tried it once. Understandably, Norman was less than chuffed. Well, perhaps more than once. It comes with the territory when you have put yourself into contention on the biggest stages so often and ended up not winning so many of them. But golf being such a mannerly game, the word ‘choke’ is not generally bandied around. Professional golfers are naturally sensitive to the accusation, particularly when, as Bobby Jones pointed out, the ‘six inches between the ears’ have such a vital impact on the difference between success and failure.

As Colin Montgomerie knows all too well, being a foreigner who is purported to be one of the best players in the game (and therefore a threat), but who manages not to win the biggest titles in America, is considered fair game for those who are inclined to verbal antagonism. The trick is never to let it show. At the 1991 Masters, Tom Watson told Ian Woosnam, as the Welshman was on his way to victory, that the old pros’ method of dealing with hecklers was to turn round, touch the peak of your cap politely and say simply: ‘Fuck you very much.’ Monty was unable to master the art of never letting it show and, in the mind’s eye, is still

to this day standing on the 71st green at Congressional waiting for the gallery at the 1997 US Open to quieten down.

New York galleries are hardly shy and retiring and Norman suffered plenty of abuse as he tied with, and then lost a playoff to, Fuzzy Zoeller at the 1984 US Open at Winged Foot. Two years later at Shinnecock Hills, just months after losing the 1986 Masters to Jack Nicklaus, Norman was again in contention at the US Open. Leading by three at the turn in the third round, he dropped a shot at the 10th and then had a double bogey at the 13th. Now Lee Trevino, his playing partner, was level with the Australian. On the 14th fairway, Norman and Trevino were waiting for the group ahead to leave the green, when a spectator shouted: ‘Are you choking, Norman? Are you choking just like at the Masters?’