Falling to Earth (37 page)

Authors: Al Worden

I had enjoyed my six days in lunar orbit. It sounds like a hell of a long time, but there was so much to see and explore that I never grew bored. The sunlit part of the moon shifted as the days went by, so there were always new places to view. I could have happily spent a few more days there—the same feeling I get at the end of a great vacation. But it was time to go home.

I busily checked the temperatures and pressures of our main engine’s propellant tanks. If there was ever a time that I felt particularly tense or nervous on the spaceflight, this was it. With no lunar module, we were down to one engine. If it failed, I’d be looking at the lunar surface for the rest of my life, which would be as long as our oxygen lasted. In addition, without

Falcon

attached to the nose,

Endeavour

was a much lighter machine. If our engine’s control system did something wrong, I would have to react instantly, or we could be quickly rocketed in the wrong direction.

As Earth began to set on the lunar horizon and we prepared for our final pass over the lunar far side, Joe Allen wished us luck with a final nod to James Cook’s era of exploration. “Set your sails for home,” he told us. “We’re predicting good weather, a strong tailwind, and we’ll be waiting on the dock.”

“Thank you very much,” Dave replied. “We’ll see you around the corner.” Mission control would not know the success of our engine firing for sure until we emerged from behind the moon.

Then we lost radio contact with Earth for the last time. I thought back to my television interview with Fred Rogers. A child had wanted to know if I’d be scared flying to the moon. It was important to be honest. Yes, I replied, risky work can be scary.

When the engine lit, it was a real kick in the pants. I could feel the steady acceleration as it burned for over two minutes. I warily watched the gauges that told me our engine was burning smoothly and steadily, speeding us on the correct curved pathway out of lunar orbit and back to Earth.

To my relief, the burn was beautifully smooth. Soon we rounded the far side again and, as we climbed away from the moon on our new course, Dave could announce “Hello, Houston.

Endeavour

’s on the way home.”

We shot away from the moon at more than fifty-seven hundred miles per hour, turning the spacecraft so we could look back and use up much of our remaining film on the rapidly receding moon. “We’re almost speechless looking at the thing,” Dave told mission control. “It’s amazing—looks like we’re going straight up,” he added, commenting on our new burst of speed. “We’re leaving, there’s no doubt about that.”

It was clear from my first glimpse out of the window that the moon was shrinking. And the dramatic sun angle highlighted new features for our parting glimpses. Parts of the lunar south pole and the immense crater Tycho were visible for the first time, and I took pictures with a mixture of fascination and sadness. I’d never get to see them up close again.

“That’s a pretty good view after all those days of going around and around, isn’t it?” Dick Gordon radioed from mission control.

“Yeah,

boy

,” I replied, scanning the rugged terrain that bulged out in our direction. “We’re looking at new territory.” For the first time in a week, I could gaze at the entire sphere of the moon in one window. “You can see it all in one big gulp, and boy, what a gulp!” I continued to describe lava flows that we had not spotted before, until the details were too hard to make out anymore.

I fiddled with some SIM bay experiments, placed the spacecraft back into barbecue mode, then settled in for our three-day coast back to our home planet. Mission control signed off, reminding us that “our ever-watchful eye will be on you while you sleep.” Before the day was out, Dave shared a pleasant thought with Houston. “We’ve got another unanimous vote up here. That was really a great trip.”

It almost sounded like the mission was over. But as I went to sleep, I knew that tomorrow would be one of the most important days of my astronaut career. I would make the first-ever deep-space EVA.

When I woke the next morning, I first had to carry out some navigation. We had one shot to get back home, and I wanted to be on course from the beginning. While Houston kept an eye on us to make sure we didn’t stray out of a general path of certainty, I hoped to prove that it was possible to navigate to and from the moon without their help. I was aiming for a narrow sliver of horizon on a planet tens of thousands of miles away, and there was no margin for error. This far from Earth, the tiniest changes in direction could result in huge errors once we had traveled the remaining distance in our voyage.

I used my sextant and measured the angle between Earth’s horizon and my preselected stars. However, I also had to choose the right

place

on the horizon. Our planet is about eight thousand miles across, and the horizon is only fifty miles thick. That sounds tiny, and it looked tiny from so far away, but fifty miles was too wide for what I needed to do. I needed more accuracy.

In my training I had calibrated my eye for a specific part of the atmosphere. Between Earth’s surface and the blackness of space, the atmosphere looked like narrow bands of different colors, mostly subtle differences of reds, magentas, and blues. I had experimented in simulations on Earth to identify a thin color line I could find consistently. I looked for a particular light blue within the atmosphere when navigating, and this reduced the fifty-mile width to a much smaller path as we left the moon. It worked even better than it had in the simulators—we stayed firmly on track.

Mission control called again and jokingly congratulated me on the accurate navigation. “They’re awarding the honorary ‘Vasco da Gama Navigation Award’ for excellence in this,” Joe Allen teased, referencing the early Portuguese explorer who’d sailed from Portugal to India—and back again, which was more on my mind at that moment.

“Be advised,” Joe added, “you are leaving the sphere of lunar influence and it’s downhill from here on in.” We were still much closer to the moon than the Earth, but because our planet is so much larger, its gravity pulled on us more. We were now truly falling to earth. It meant nothing to us in the spacecraft—there was no physical sensation of movement, no outside indication of our incredible speed as we shot through the empty black void.

There was a slight sense of disconnectedness on the long journey out and back between moon and Earth. At every other time in my life, even in Earth or moon orbit, there was a sense of the ground being below me. Here, both Earth and moon were remote, faraway places. I found it really stimulating. To see the sun, Earth, and moon in sequence as our spacecraft slowly spun made me think more about the moon rotating around Earth, which in turn rotated around the sun. I’d read about this in school and knew it intellectually. However, to be out in deep space and see it firsthand made me sense it on a deeper level. The human species seemed both more and less significant now: less, because I felt dwarfed in this vast blackness; more, because I was able to see it and explore it.

It was time for the three of us to float back into our spacesuits and help each other zip up. We placed guards over the control panel switches so I wouldn’t kick them as I floated outside. I disabled some spacecraft thrusters: the last thing I needed was a thruster to fire as I floated by. We also stowed and tied down loose items in the cabin. After the work Dave and Jim had done to collect moon rocks and place them in sample containers, we didn’t want our prizes to float out of the hatch. We worked slowly and carefully through our preparations for my spacewalk, and everything went very smoothly. I was glad because we were about to do something never tried before in the program.

“You have a

go

for depress,” mission control told us. We slowly began to let the oxygen out of the cabin through a special valve in the hatch. Everything in the spacecraft looked the same, but I knew now that if I took off my helmet, I would die. The inside of

Endeavour

was soon as airless as the deep space we traveled through.

“We’re getting ready to open the hatch,” Dave reported. “Okay. Unlatch.” I depressed the safety lock that meant the hatch couldn’t be accidentally opened, always a wise precaution in space. I pumped the hatch handle to rotate the latches out of their locked position. Then, with a careful push, I swung the hatch open.

Apart from briefly floating inside

Falcon

days before, I hadn’t left the confines of

Endeavour

for eleven days. I’d last slid through this hatch on the launchpad in Florida. Now I was about to float out of it more than 196,000 miles from home, into the deep space between Earth and moon. It was a thrilling thought.

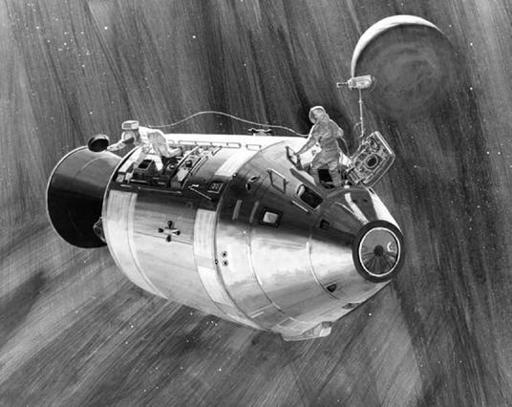

“The hatch is open,” I announced. The open, square hatchway now framed only deep blackness. I poked my head outside and carefully mounted a TV camera and a movie camera on the hatch so they could capture my spacewalk. Then, grabbing the nearest handrail, I soundlessly floated outside into the void.

I paused a moment and waited for Jim to poke his head and shoulders out of the hatchway behind me. He would stay there and keep an eye on me while I made my way down the side of the spacecraft. Other than our service module glinting in the sunlight, it looked

really

black out there. I looked down the length of the SIM bay. “The mapping camera is all the way out,” I reported to mission control. It was one of the pieces of equipment that had begun to fail as the flight went on, and I had suspected it could no longer retract all the way back into its housing. Sure enough, it was sticking out. This could complicate my spacewalk a little as I would have to float over it without losing my grip on the handrails. “You ready, Jim?” I asked. “I’ll work my way down.”

After eleven days in space, I was accustomed to weightlessness. Working outside turned out to be a lot simpler than I thought. With one hand on a handrail, I could turn my body with my wrist. The SIM bay was slightly to the left of the hatch, so I first needed to swing across the face of

Endeavour

. I let my legs float up, and then I swung around and worked my way down the side of the spacecraft, hand over hand, never using my feet. It was even easier than in the water training tank.

I floated over the stuck mapping camera, then rotated myself on the handrail, placing my feet in special restraints. I took a quick look around while Jim floated into position.

I hadn’t really had a sense of where I was until this moment. Standing upright on the side of the spacecraft, attached only by my feet and the umbilical that loosely snaked back to the spacecraft hatch, I had a fleeting sense of being deep under the ocean, in the dark, next to an enormous white whale. The sun was at a low angle behind me, so every bump on the outside of the service module cast a deep shadow. I didn’t dare look toward the sun, knowing it would be blindingly bright. In the other direction, and all around me, there was—

nothing

. It’s a sensation impossible to experience unless you float tens of thousands of miles from the nearest planet. This wasn’t deep, dark water, or night sky, or any other wide open space that I could comprehend. The blackness defied understanding, because it stretched away from me for billions of miles.

But there wasn’t time to ponder it too much. I had work to do. I pulled the cover off the panoramic camera, released the film cassette and tethered myself to it. It came out even easier than I expected, although it felt a little bulkier than in simulations. Keeping one hand on its handle, I used my other hand to pull myself back toward the hatch. When I came to the stuck mapping camera again I had to let go of the handle for a second to maneuver over it. But it was only for an instant as I swung my legs out wide, then I had a firm grip once again.

Jim waited for me at the hatch. “Would you like to get hold of it?” I asked with a laugh as I passed him the film. Jim tethered it inside, released the tether attaching me to it, and I was free to float back down again. It was all going so simply. If I had known that Jim, now blocking the hatch, had heart problems, I may have felt much less secure. If he’d had a heart attack at that moment, we’d all have been in danger.

But Jim was okay. While Dave stowed the panoramic camera film deeper in the cabin, I floated back down the side of the spacecraft. “Beautiful job, Al baby!” Karl Henize radioed from Earth. “Remember, there is no hurry up there at all.”

“Roger, Karl,” I replied as I grabbed the handrail again. “I’m enjoying it!”

I floated back down the SIM bay, much faster this time. I’d been asked to look at one of the panoramic camera’s sensors. It hadn’t worked well during the mission, and the engineers on Earth wondered if there was perhaps a crack or contamination in the lens. I floated over it and peered in. “There’s nothing obscuring the field of view. The glass is not cracked,” I reported. “It’s perfectly clear.” Engineers would later find that the problem with the sensor wasn’t with the lens after all, but the signal.

I also had a look at the mass spectrometer. We’d had trouble with its boom, and when I peered at it closely I could see it hadn’t completely retracted, a problem that seemed to happen only when the equipment was in shadow. It had been too cold to work correctly. I could explain exactly what the problem was, a luxury mission control rarely enjoyed with instrumentation on the outside of a spacecraft.