Fanny (78 page)

Authors: Erica Jong

I hope this novel is true to the spirit, if not the letter, of the eighteenth century, for I am well aware that I have often stretched (though I hope not shattered) historical “truth” in order to make a more amusing tale. Anne Bonny, for example, disappears from the history books in 1720. What she did in the next years of her life nobody knows, thus the novelist is free to imagine. The Hell-Fire Clubs were outlawed in 1721, but I am taking the license of assuming that they must have continued to meet in secret, though their members were cautious not to mention where or when. In my description of the Hell-Fire caves, I have drawn partially on those still visible at the village of West Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, which I realize were not built until after the date of my story. My “Monks” are of course inspired by the notorious Medmenham Monks, who flourished later in the century. Other than that, I have tried to be true to chronology.

Lancelot Robinson is a “Pyrate” of my own invention, yet not long after I imagined him, I chanced to read about the French Pirate Misson, whose motto was

A Deo a Libertate

and whose Utopian dreams were very like those I imagined for Lancelot. Piracy buffs will recognize that Lancelot’s “Pyrate Articles” are much like those of Bartholomew Roberts’, with a few items from George Lowther’s articles thrown in for good measure. “Pyrate” articles tended to be rather similar—but none that I have read mentions women except to proscribe them. Yet there

were

famous female “Pyrates” in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and none more famous than Anne Bonny.

Swift, Pope, Hogarth, John Cleland, Theophilus Cibber, Anne Bonny, and Dr. William Smellie, I have imagined as fictional characters within the parameters of the known facts of their lives. Their entry into this book as comic characters is intended as no slur upon the greatness of their achievements. Swift and Hogarth, in particular, are among the most extraordinary artists the world has ever known.

For the arguments regarding the pros and cons of the slave trade, I am indebted to the sea diaries of the period, particularly Captain Snelgrave’s. For Fanny’s adventures as a “Pyrate” I am indebted, like most writers on piracy, to Captain Charles Johnson’s 1724 book:

A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates from Their First Rise and Settlement in the Island of New Providence to the Present Year.

Many scholars believe that Johnson was really a pseudonym for the prolific Daniel Defoe. I am not certain this is true, because the writing in the book seems inferior to Defoe’s, but the volume is a treasure trove and every writer on piracy has used it.

For Fanny’s adventures in the “skin trade,” I am indebted to

A Medical History of Contraception

by Norman Himes, and the gracious help of Jeanne Swinton, librarian at the Margaret Sanger Library of Planned Parenthood of New York.

As for my obstetrics, Caesarian section is, of course, an ancient practice known both in Greece and Rome and in “primitive” cultures today. The first successful recorded Caesarian in British medical history took place in 1738, was performed by a midwife, and executed with razor, tailor’s needle, and silk thread. The mother not only survived, but recovered well and rapidly. Still, the Caesarian has never ceased to be a controversial operation, and the arguments about it tend to be fervid and political even in our own time. I assume that, if the first successful recorded Caesarian took place in 1738, there must have been earlier unrecorded successes, perhaps not revealed because the Witchcraft Acts were still in force. At any rate, I chose to have Belinda delivered thus for the purposes of my plot.

For the witchcraft material, I am indebted to the crucial anthropological work of the late Dr. Margaret A. Murray, though my witches owe as much to the fairy tale as they do to anthropology. I have placed them in Wiltshire, though I know that Wiltshire was not as famous for witches as, say, Lancashire. These Wiltshire witches are very much my own invention.

Readers who know the introduction I wrote to

Fanny Hill: or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

(Erotic Art Book Society) are aware that it is one of my favorite books; thus I do not share my heroine’s opinions about Mr. Cleland. Nevertheless, I thought it amusing to make her pique at Cleland the impetus for writing her own memoirs. No disrespect to that classic of erotica,

Fanny Hill

, is intended.

I must also acknowledge a debt to Ditchley Park in Oxfordshire, one of the many beautiful English Country Houses that inspired me with the settings for this book. Those who have stayed at Ditchley as guests of the Ditchley Foundation may recognize that Lady Bellars’ beloved poem on the superiority of dogs to people is to be found upon a painting of Sir Henry Lee (ancestor of General Robert E. Lee and the Virginia Lees), in the Tapestry Room at Ditchley. But my fictional Lymeworth draws only partly upon Ditchley for inspiration. The other houses I have visited are too many to list and I am particularly grateful to Britain’s National Trust that they are still standing.

A note on orthography: Eighteenth-century buffs will know, of course, that capitalization and spelling were highly capricious in that age, and only beginning to be standardized at a later date. (Most of the eighteenth-century novels we read—

Tom Jones

,

Moll Flanders

, et cetera—have been reset to suit contemporary styles of spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.) I have opted for my own compromise here, capitalizing nouns and catch phrases with regularity, while verbs and most adjectives are lower-case. I have therefore been far more predictable in my capitalization and orthography than the average eighteenth-century author, but far less predictable than the average twentieth-century author. I do follow the eighteenth-century practice of capitalizing certain words for emphasis—a practice we have largely abandoned except in ironic writing. It was my intention to give

the flavor

of eighteenth-century prose, without, however, forcing my readers to read

f

’s for

s

’s or puzzle through a maze of utterly erratic capitalizations.

I should also add that I started out with the notion of using no language but the language in use in the first half of the eighteenth century, and to a large extent, I adhered to that rule. But I eventually found that the rule was impossible to follow. First, the

Oxford English Dictionary

only records written language, not spoken. Second, some words have so changed their meanings in two hundred and fifty years that to use them would thoroughly puzzle the modern reader and interfere with the pleasure of reading. Also, for comic purposes, I have given Fanny some language that was somewhat antiquated and rhetorical even in her time. When in doubt, I have opted for pleasure, not rigid adherence to rules—even those of my own making.

It may be objected by some that Fanny is not a typical eighteenth-century woman—and I am well aware of this fact. In many ways her consciousness is modern. But I do believe that in every age there are people whose consciousness transcends their own time and that these people, whether fictional or historical, are those with whom we most closely identify and those about whom we most enjoy reading. I have tried to write an interesting and entertaining novel, not an historical treatise, so the development of my heroine’s character has always been more important to me than the setting in which we find her. I hope this book will convey something of the fascination I have had with eighteenth-century England, its manners and mores, but, above all, it is intended as a novel about a woman’s life and development in a time when women suffered far greater oppression than they do today.

This book is lovingly dedicated to my mother, Eda Mirsky Mann, and to my daughter, Molly Miranda Jong-Fast.

ERICA JONG

A Biography of Erica Jong

E

RICA

J

ONG

is an award-winning poet, novelist, and memoirist, and one of the nation’s most distinctive voices on women and sexuality. She has won many literary awards: the Bess Hokin Prize from

Poetry

magazine (also awarded to Sylvia Plath and W. S. Merwin); a National Endowment for the Arts award; the first Fernanda Pivano Award in Italy (named for the critic who introduced Ernest Hemingway, Allen Ginsberg, and Erica Jong herself to the Italian public); the Sigmund Freud Award for Literature, also it Italy; the United Nations Award for Excellence in Literature; and the Deauville Award for Literary Excellence in France.

Raised by artists in the intellectual melting pot of New York’s Upper West Side, Jong graduated from the High School of Music & Art and Barnard College, where she majored in writing and Italian literature. She then completed a Master’s degree in eighteenth-century English literature at Columbia (1965) and began PhD studies. She first attracted serious attention as a poet, publishing her debut volume,

Fruits & Vegetables

, in 1971 and her second,

Half-Lives

, in 1973.

Also in 1973, she published the book for which she is best known. Partially drawing on Jong’s early life, as well as her wild imagination,

Fear of Flying

, hailed by John Updike as the female answer to

Portnoy’s Complaint

and

The Catcher in the Rye

, is about a woman trying to find herself and learn how to fly free of her repressions. Isadora Wing seeks to discover her soul and her sexuality, and in the process, she delves into erotic fantasy and experimentation, shocking many critics—but delighting readers.

While the book’s explicitness inevitably drew controversy, the novel has endured because of its psychological depth and wild humor. Its heroine, Isadora Wing, whose quest for liberation and happiness struck a chord with many readers, galvanized them to change their lives. The novel gathered momentum, eventually landing on top of the

New York Times

bestseller list. It has since sold over twenty-six million copies in forty languages. It has been as beloved in Asia, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and South America as in North America, and has been written about, studied, and taught in universities.

Erica Jong followed Isadora Wing through three additional novels,

How to Save Your Own Life, Parachutes & Kisses

, and

Any Woman’s Blues

. She has also published eight award-winning volumes of poetry and written brilliant historical fiction, like

Fanny

:

Being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones

, a fantasy about what would have happened if Fielding’s Tom Jones had been a woman. She has written a glittering novel about sixteenth-century Venice (where she has spent many summers),

Shylock’s Daughter

or

Serenissima,

and an amazing recreation of ancient Greece, entitled

Sappho’s Leap

. Her moving memoir,

Fear of Fifty,

and her writer’s meditation on the craft,

Seducing the Demon

, have also been bestsellers in the United States and abroad. Her most recent publication is an anthology of women writing about the best sex they’ve ever had,

Sugar in my Bowl

.

Dividing her time between New York City and Weston, Connecticut, Jong lives with her husband, famed divorce attorney Ken Burrows, and a standard poodle named Belinda Barkowitz. Jong’s daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, is also a writer, and the mother of Jong’s three grandchildren, an eight-year-old and four-year-old twins.

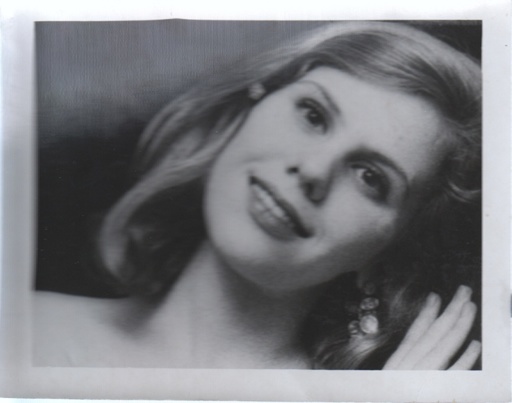

Jong posing in her grandfather’s portrait studio at a young age. Jong grew up in Manhattan’s Upper West Side and enjoyed a childhood of music lessons, skating lessons, summer camps, and art school.

Jong at age eleven or twelve, meditating on her future as a writer—and perhaps which nail polish to try next.