Faraway Horses (12 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

One fellow in the class was nicknamed Polack. I felt embarrassed calling him that, but he wouldn’t answer to his real name. He liked his nickname; he apparently was quite proud of his Polish heritage. Polack had a sorrel horse that was a little on the volatile side, kind of a hand grenade with a saddle strapped on.

When we took the break, Polack rode up to the edge of the arena with the others, stopped at the fence, hooked a leg over his saddle horn, and tipped his hat back, just like

the Marlboro Man posing for a cigarette ad. His wife handed him a container of water, a plastic milk jug with ice in it.

When Polack tipped that jug up and took a big slug of water, the ice hit the bottom of the jug. The young sorrel spun around and left, hell-bent for election. Polack still had his leg hooked over the saddle horn and his hat tipped back, and he was still holding on to this jug. Even though realization and terror overtook him, he couldn’t seem to let go of the jug. Having seen a similar move with Ayatollah and my coat, I felt “the pain of my brother.”

His horse was at a full gallop now, a red blur across the arena. I quickly turned on my microphone and pleaded, “Drop the jug! Polack, drop the jug! Please,

please

drop the jug!” I repeated my plea again and again as he went down the arena, which was about three hundred feet long and surrounded by a fence made of stout two-inch steel pipe.

Just as he raced by me, the light came on. He looked down at his hand and the idea seemed to register on Polack’s face. He dropped the jug. But his horse was still at a full gallop, and even though Polack had dropped the jug, they were so close to that pipe fence, I was sure that he had failed to save himself.

It was my first real heavy year of doing clinics, and there I was in the middle of a boiling arena, dust everywhere, and my first fatality was about to happen. As I prepared for the wreck of the century, both Polack and his horse disappeared in the dust.

A miniature mushroom cloud boiled up over the arena. Then, as the dust slowly began to settle, I just about fell over. I felt like one of those cartoon characters with buggy eyes on big springs.

There was Polack—still on his horse, his leg still hooked over his horn, his hat still tipped back on his head. His horse had made a perfect sliding stop, ending with no more than a quarter inch to spare in front of the fencing. The track on the dusty surface of that arena was the most perfect parallel-lined “eleven” I’d seen in a long time.

Polack turned around and looked at me and said, “Yahoo!” The crowd erupted in applause.

After that averted mess that day, I told Polack he was welcome to stay, but with the kind of luck he had, he really didn’t need me. The last I heard, he was still alive and well somewhere in Arizona. I hope his luck holds out for him.

I’ve heard a lot of people say they’d rather be lucky than good, but not me.

Mike Thomas, a friend who had managed the Madison River Cattle Company before he tired of the Montana winters and moved down to Arizona, set up a clinic for me at the Mohawk arena in Scottsdale. We had quite a large group of people, and as it happened, the manager of an Arabian horse ranch that had canceled one of my clinics the year before was one of them.

I was doing a trailer-loading demonstration on a little Appaloosa mare, leading her off my left shoulder from right to left and getting her to lead past me while I stood still. Once I had her going smooth and could stop her on the lead rope and then get her to step back, we moved to the trailer, where I started loading her and backing her out.

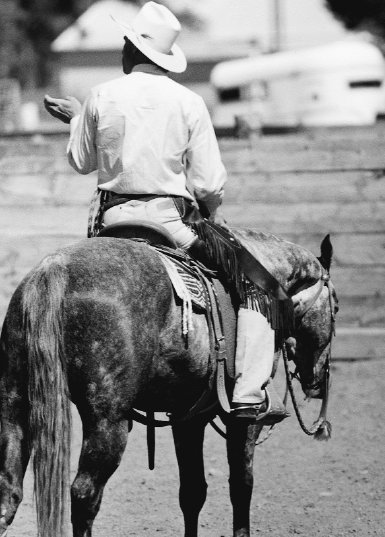

Buck on his saddle horse Jack, answering questions at a clinic. Question-and-answer sessions at Buck’s clinics last as long as they last—sometimes long after the sun goes down.

Each time I prepared to load the mare, I’d give her a little more rope and step farther away, thus widening the gap between the trailer and me. If she chose to go through the gap rather than into the trailer, I’d take a step forward and divert her into it. If I hadn’t and she had gotten used to going between me and the trailer, it would have been the equivalent of letting her run me over.

Once the mare was confident loading that way, I worked my way up to the left rear of the trailer. I began loading her on an even longer rope, moving her in an arc from my right to my left. I’d pet her and reassure her, back her out again, play out a little more rope, and lengthen the arc. After a little while, I was standing by the tandem wheel so I was out of her sight when she loaded.

By the time I was able to stand by the truck’s side mirror, I had to replace her halter with a thin nylon rope around her neck. The mare was real responsive now, and since she was on forty to fifty feet of rope, anything heavier than the nylon would have made her turn and face me.

I finally got the mare to the point where I could sit in the front seat of the truck and feed coils off the rope out the side window. The mare promptly went to the trailer and loaded, which seemed to really impress the folks at the clinic.

At the end of the day, the manager of the Arabian outfit came up to me. He was very excited about what he had just seen. He said he had an expensive Arab stud that had never had a successful trailer ride, and he asked me if I would load him.

I hadn’t forgotten that the manager worked for the folks who had betrayed my trust and put me in a bad spot by canceling that clinic. So I said, “Okay, it’ll cost you five hundred dollars.” In those days I charged a hundred dollars to load a horse, and this was my way of telling him to go to hell.

He didn’t even blink. Instead he asked, “When can you show up?”

I wished I’d asked for five thousand, but I had to be good to my word. The next day after I’d finished my clinic, I drove to the fellow’s farm. I figured I needed to get the horse pretty well trained for that kind of money, but I got him loading into the trailer without much of a problem. In fact, I got that stud horse to the point where, turned loose beside a pen of mares, he’d walk away from them and get in the trailer.

One person watching this demonstration was a local used-car salesman who had married into a very wealthy family. He was running off at the mouth with some of the other spectators, and I heard him say, “I bet Brannaman couldn’t load our horse.”

His wife, who had ridden in one of my public clinics and was interested in my kind of horsemanship, said, “Well, honey, I’ll bet you a thousand dollars he can.” Then she

asked me, “Buck, would you be interested in going partners on this?”

I jumped at the opportunity. “Bring him on.”

Their horse was a famous Arab halter show horse imported from Europe for more than a million dollars. In those days when a horse needed to show spirit to win a halter class, in which animation seemed to matter as much as proper conformation did, many trainers and judges confused “spirit” with terror. In order to get the right expression, some trainers kept their horses in tiny stalls and ambushed them in the dark with fire extinguishers so that any sound would provoke a terrified “look of excitement.” Another favorite trick was to cross-tie a horse in water and hook electrodes to his neck so that he’d tense up when they hit the switch.

That kind of terror tactics had gotten this horse to the point where he was unsafe to work with or just to be around. His stall door had a double padlock so no one would accidentally walk in on him. His owners had catwalks installed on both sides of his stall. To get him to me, his handlers climbed up on them and used long poles with hooks at the ends to grab his halter. Once they had the horse more or less under control, they chained him from both sides and muscled him into a rented semitrailer. It was no easy job, and it took several hours.

When they got to their destination, the handlers had to use their chains to bring the horse into a small arena surrounded by a low fence. When he immediately broke free and began racing around the arena, I saw how dangerous he

was. He wore a halter with a chain shank over his nose, and I could tell that he’d had it on for some time because his nose was terribly scarred.

I entered the arena riding my saddle horse. If I’d come in on foot, he would have attacked me. My first job was to get a rope around his neck so I could control his feet. The fence was so low, if I roped him when he was in a corner, there was a good chance he’d jump the fence and break a leg. Plus, if I missed my shot and he jumped out, he would find himself in the middle of one of the busiest roads in Scottsdale. Neither of the prospects was anything I wanted to think about. Aside from the danger to the horse, I wasn’t in any position to pay for my mistakes in those days.

After some fifteen minutes, the horse finally moved to the middle of the arena. The roping gods must have been with me, because I roped him around his neck and got him stopped. However, now I had to keep him at the end of my sixty-foot rope, because any closer and he would have crawled up in the saddle with me.

I worked with him the same way I would work a horse I was teaching to lead, getting him to “turn loose” to me. Occasionally, this horse would give to the rope and put some slack in it. However, feeling any pull caused him to immediately begin ducking his head and thrashing around as if to avoid an imaginary whip. He even got down on his knees, laying his head on the ground and closing his eyes as though having a recurring nightmare of past abuse. To imagine what this horse had been through was painful.

After a lot of sweat and tears for that little horse, I was able—after an hour or more—to bring him close enough that I could slip the halter and shank off without being bitten.

Reaching across my saddle horse, I placed my hands over the Arab’s nose and rubbed him where he’d been chafed for so many weeks. His response was to lay his head across my leg up on the saddle and close his eyes. He may not have felt this safe since he’d been with his mother. He’d finally met a human who knew how to be his friend.

He and my horse walked around the small arena, his head still in my lap. There was salt on my chaps from rubbing up against many sweaty horses, so when we would stop, the stallion would affectionately lick my chaps. When I put my hands in his mouth around his lips, he gave me no trouble. He wasn’t defensive. He had no plans to strike me, bite me, kick me, or even to leave me.

The Arab was leading well, so at this point I felt safe enough to step off my saddle horse and approach the horse trailer. I was now ready to begin what I had been hired to do, although most of my work had already been done.

Getting the horse to load didn’t take very long because we had become partners. I could steer him into the trailer by his tail; I could even pick up three tail hairs and back him out of the trailer without breaking one of them.

The horse became so quiet and relaxed, some in the crowd began to worry that he couldn’t win a halter class looking the way he did—without the look of terror that’s often confused with what they think is “spirit.” Hearing

them say that made me realize how hard it was to understand how seeing a horse in a relaxed frame of mind could be any cause for worry. These people were as different from me as any people I’d ever met.

As the little horse stood quietly with his head in my arms, a lady in the crowd who owned a local Arabian farm of her own spoke up. “Buck, now that you’ve gotten this horse coming around the way you have, when would we be able to start with the whips again? Would we be able to start tomorrow, or would we have to wait till next week?”

She had no idea what she was saying. It was the most bizarre thing I’d ever heard, and from a woman who appeared to be so sophisticated. How could she say something so uncivilized?

I couldn’t take it, not after what the little horse been through. “Some of you can go to church on Sunday and claim to be holier than thou, but the other six days of the week you’re torturing horses and committing crimes against them. You make me ashamed to be a human being.”

But that wasn’t all that bothered me. That little horse had made a friend that day. He appreciated what I had done with him—I know he did. Yet I went away with a sick feeling, wondering if maybe I had done wrong. On one hand, I had helped him, but I had also shown him there was something truly good in life that he would always miss.

I later learned that he went back to his same life. In that world of barbarians, defense was his only means of survival, and I worried that I might have taken it away from him.

Even years later, I still wonder if he remembered me, the man in the cowboy hat who for just a few hours had been his friend.

You wonder what a horse knows and how deep it runs.

My brother-in-law, Roland Moore, is a good cowboy. Roland married the Shirleys’ daughter Elaine, and was working as a cowboy on The Flying D ranch. When we first met I was only twelve and he was twenty-eight, so due to the age difference, our friendship didn’t amount to much at first. I saw him off and on, but it wasn’t until I was a little older that we started riding and working cattle together.

When Forrest and Betsy were ready to retire, Roland and Elaine moved in and took over the place. It’s called the Cold Springs Ranch now, and they all ran it together until Elaine died in 1999. The Flying D and Spanish Creek have since been sold to media mogul Ted Turner, who started a buffalo-raising operation there.