Faraway Horses (18 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

We’re supposed to be the smart ones, but it’s amazing how people put little thought into working with their horses. They don’t understand that a horse reacts the way he does because to him it’s a matter of life and death. I often tell people in my clinics that the whole class could get on their horses and take off running, bucking and bouncing off the fences. That chaos wouldn’t influence the horse I’m sitting on because he and I have a good thing going on. He doesn’t go anywhere without me, and I don’t go anywhere without him. Other horses and riders have no influence on us because my horse is secure within himself.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could raise our kids with that sort of independence? As parents, that’s really what we’re looking for. You look at kids who get into gangs or hang around a bunch of punks who will lead them down the wrong path. If the kids had been better equipped mentally and psychologically before they got around the bad element, the bad element wouldn’t have had a chance.

You can’t blame many kids who end up in gangs, and you can’t blame it all on the kids who lead them into temptation. If their parents had given them a better background, they never would have ended up in trouble. Working with young horses is the same deal. In a sense we’re parents there, too. We have a responsibility to help the horses become comfortable in their lives and understand how to fit in.

Herdbound horses are insecure, too, but for different reasons. A herdbound horse is fine if you go where the group goes, but quite often if you try to take him away from his pals, he may buck you off, tip over on you, or jump sideways out from under you. That’s the kind of behavior that can get you hurt.

The horse doesn’t feel secure with you because he doesn’t feel secure within himself. As the rider, you can help him to stand alone and be by himself. Horses are very social animals that are meant to be in a herd, yet if you increase his sense of security with himself, your horse will be fine away from the herd as long as he has you with him.

A herdbound horse may have been left in the paddock for so long that he doesn’t want to leave home, or he may be so used to company that he doesn’t want to leave other horses and riders on the trail.

To start working on the problem, I’ll have a group of people on horseback in a big pasture. They’ll just be standing in a small group with room enough for a horse to move between them. I’ll then pick a goal for my herdbound horse: a spot under a shade tree at the end of the meadow or some distant corner. I might loosen my reins and put them up on my saddle horn, start asking the horse to move with my legs, and ride near the group. I don’t steer him with my reins or try to direct him with my legs. I simply cause movement. What I’m doing is making what he thought was a good place to be—the herd—a little difficult for him. I want him to understand that being alone with me in the corner of the pasture or under the shade tree is where he’ll find the most security and comfort.

Rather than force my idea to become his idea, I

allow

it to become his over a period of time by making it difficult for him to stay with the herd. We simply walk and trot with nothing abusive happening. I tell the horse through my actions, “If you want to stay here with your pals, that’s okay with me. I have no problem with that, but the conditions I’m putting on your staying with them is that you have to be in motion. They might get to stand comfortably, but you have to be in motion.”

After a few minutes the horse may make a small circle away from the herd. When he does, my body becomes one

with him. I pet him and rub him and am as soothing as I can be. Be still, and he’ll go a little way and come right back to the herd—the herd is like a magnet, and he’ll be drawn back with more force than I’ve been able to exert riding him off by himself.

After a few more minutes of keeping him in motion and thus making the herd an uncomfortable place to be, his circle will become a little larger. On the way out away from the herd, I pet him and rub him and praise him. When the herd draws him back, I keep a constant energy flowing through him. I turn the energy up in volume as we get closer to the herd, and I turn it down as we get farther away. It’s kind of like the “hotter-colder” game.

With a horse that has a light feel to your leg, you may need only to ride him with a little faster rhythm to encourage him to step out and be more alive. But typically, a herdbound horse has a tendency to pay more attention to the other horses and what they’re doing than to listen to you. He tunes you out, so you may have to keep a firm leg on him in order to initiate and then maintain his energy. Sometimes, you can tap him with the tail of your reins to get his “life up.”

Once you get the horse to respond, don’t allow him to stop moving at the wrong time. If you do, he’ll perceive stopping as a reward. Be careful not to let the energy diminish until the horse is in a place where you want him to be mentally and physically; that is, somewhere away from the herd or the barn.

Over a period of time, the horse’s circles grow larger and larger. At first, he may move a hundred yards from the herd and stop. When he’s in the general vicinity of the goal I’ve chosen, I pet him and rub him. He may not yet be sitting under the tree I’ve chosen in the corner, but he’s closer to it than he was a while ago. I’ll sit there for a while and I’ll rub him, and we’ll take a little break.

Then I’ll ask him to move his feet again with my legs. I don’t care where he goes. Typically he’ll turn around and hotfoot it right back to the herd, looking for that secure place. But again, as always, when he returns to the herd, I make it difficult for him to be there. Soon he starts looking again for that place where things were more peaceful, so he moves a little farther out away from the herd, maybe toward the place he was resting before or even a little beyond it. When he gets there, I’ll let him rest again.

The horse will build on what we’re doing because I’m allowing his mind to search. I’m allowing him to change, to make changes within himself, without treating change like a life-threatening emergency. Even a real problem horse doesn’t need more than an hour or two before I can comfortably ride with my arms folded to the tree in the corner of the pasture. There we’ll sit for long periods of time. I’ll pet him and rub him, let him enjoy the shade, and we’ll just be together.

When I ask him to move again, he may turn around and lope back to his pals, but when we get there and he tries to stop, I keep him working at moving. That reaffirms that being with the herd isn’t as secure or as comfortable as he

thought it was. He’ll look for his “comfort” tree in the corner of the pasture.

At the end of the lesson, I’ll know that I’ve finished when the horse sits under “our” tree for a few minutes. Then when I ask him to move his feet, he’ll take a step or two and offer to stop again. At that point, my idea and the horse’s idea are one and the same. I’ll step off him, take my saddle off, and rub him down with my hands (hands are a lot better than a brush right then because of the physical touch from a human being). And then I’ll lead him home, maybe the long way. I’ll take him back to the house and put him up, maybe give him a bite of grain, and put him away for the day.

Over three or four days, I’ll set this exercise up the same way. When we’re in the herd, I’ll fold my arms with my reins looped over the horn and let the horse simply walk off with his ears forward, open to anywhere I’d like to ride him, knowing full well that the place he’s going to be most comfortable is with me.

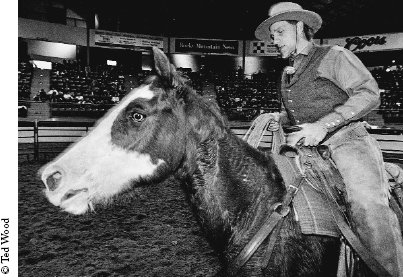

Buck puts the first ride on a horse that an hour before had never been ridden.

The same approach with your own horse will build confidence in him. You’re apt to be safe: you won’t be bucked off or have your horse tip over on top of you as he fights you to get back to his pals. You’re allowing him to be with them, but you’re simply making it a little difficult for him when he’s there.

This is an approach in which nobody loses and everybody wins. Once you’ve fixed a herdbound horse, you can ride with other people and he’ll be content, not because other horses are with him, but because you are. It’s just you and your horse, and it doesn’t get much better than that.

Herdbound horses that can’t be taken away from a group, that are too insecure to live their own lives as individuals, can be dangerous. A lot of people have been hurt or killed on such horses. To try the hairy-chested horse-trainer approach—showing your horse who’s boss by sticking a spur in him or jerking his head off or whipping him when he wants to be around other horses—won’t work. Force and violence never do. All you’ll do is destroy what was potentially going to be a friendship between you and your horse. Plus, you’re likely to get hurt. The macho approach to problem solving is used in many areas of life, and it simply doesn’t work. It doesn’t work at all.

* * *

Barn-sour horses are a lot like herdbound horses. Several years ago I did a clinic at the Mountain Sky Guest Ranch south of Livingston, Montana. The owner told me that he had a horse that his wranglers couldn’t get to leave the barn. The horse either wanted to stay around the barn or he wanted to stay around his pals in the barn—the owner wasn’t sure which, but both choices seemed pretty attractive to the horse. The wranglers had whipped and spurred him and jerked his head around, but rather than leave the barn lot, the horse bucked his rider off, rubbed him off against a fence, or flipped over backward.

When the owner asked if I would help work with the horse, I led the horse out of the barn, closed the door, and set things up so that he could move out through the barn lot gate and down the road if he chose to leave. I then asked one of the wranglers to step on and start moving him at the walk and trot.

I had the wrangler rub the horse and work his legs to keep moving. The wrangler rode the horse in figure eights and circles, all within twenty or thirty feet of the barn. I told the wrangler, “Make sure the horse understands that he can hang out at the barn with his pals as long as he’s willing to work at it. Don’t make things miserable for him, but don’t let him stop and rest.”

As I had done with the herdbound horse in the pasture, we were making the wrong choice difficult for the horse. It wasn’t long before things began to change. The horse’s ears went forward,

and after years of being obstinately barn-sour, and generally miserable in attitude and expression, he trotted right out of the barn lot, through the gate, and down the road.

After he’d gone a couple of hundred yards, I asked the wrangler to get off, rub him, and let him stand. I asked him to pull his saddle off, leave it beside the road, and walk the horse the long way home. I then told the owner that if his wranglers repeated this process for a few days, they could turn the horse’s life around.

The horse was twenty-one years old. For most of his long life he had been trying to do the best he could with what he knew. No one had ever offered him the right deal or he would have taken it. It wasn’t as though he wanted to misbehave; he just didn’t know bad behavior from good. All he knew was what people had made easy for him to do. Now, after all those years, we were asking him to change. Imagine being sixty years old and discovering that everything you thought was right about your life was actually wrong and that you had to change your entire existence.

Change can be difficult for a horse if bad behavior has become a lifelong habit. Still, he can change. This is an important lesson for people to learn, especially since people have a much harder time changing their own behavior. For example, there was a mother-daughter combination taking part in a clinic in Agua Dulce, California. Their horses were herdbound because the mother and daughter couldn’t stay away from each other. The mother was spending too much time trying to help her daughter when, in fact, she

was getting in her daughter’s way and keeping her from making progress.

The same mother and daughter then took part in a ten-day clinic at my ranch in Sheridan, Wyoming. They aren’t quite as bound together as they were, but the problem remains. I’m still working on weaning the daughter off the mother. They say it takes only twenty-one days to wean the colt off the mare. I’ve spent about six months with the mother-daughter combination, and we make a little progress every day of the clinic.

Every time I work with a horse—or a person—that’s troubled or scared, I think of how the problems and solutions relate to a human’s life, including my own. There are so many lessons, but it’s important to remember that they’re not all hard lessons and they’re not all unpleasant to learn.

Mary

A

FTER ADRIAN AND I WERE DIVORCED

, Jeff Griffith and I were good friends again. When I wasn’t off doing clinics, we teamed up to ride a lot of colts, hunt gophers, and fish during the day. At night we spent a lot of time running around, going to bars, and chasing girls.

I didn’t date anybody seriously, but I sure dated a lot. I suppose I was so afraid of having my life destroyed again by a bad relationship that I didn’t go out with any woman for very long. I kept everything pretty casual. Even though what happened between Adrian and me wasn’t my fault, I felt so much guilt and shame about having been divorced that I decided I was going to stay single.

I wasn’t really living anywhere in particular at this time. I was on the road doing a lot of clinics, and when I was back in Montana, I more or less lived up Indian Creek at Jorie Butler’s place. When I didn’t have a clinic to do, I’d ride her thoroughbreds and hang out with Jeff.

There have been times in my life when my choices in women have been fairly superficial. It was unique in my experience to meet a woman who is as beautiful on the inside as she is on the outside. Luckily I met one (given my track record, it had to have been luck). Her name is Mary.

I was doing a clinic in Boulder, Colorado, in 1986 when Mary Bower and I first met. She was one of the students, and she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen.

Mary had been a fashion model, and at the height of her career she signed with the Ford Agency in New York. Even though she was assured of a lucrative career, she didn’t like the idea of living in New York City, and after a couple of weeks she left. She moved to Los Angeles, where she appeared in a lot of print ads and commercials. She had some bit parts in television shows, but after a while she moved back to Colorado.

At the time we met, Mary was married to a former Denver Broncos football player named Rob Swenson. They had two young daughters, Lauren and Kristin. Her marriage was in trouble, but she hadn’t filed for divorce yet. Rob was living in Denver where he was trying to get a real estate business going, and she was in Boulder with the two girls.

I had had a policy of never dating my clinic students, but when I watched Mary lope circles on her colt, I decided if I were ever going to break that rule, I’d have to marry her. I loved her from the moment I first saw her. It may sound like a scene out of a Harlequin romance, but something told me

that this was the woman I would spend the rest of my life with.

After Mary had been to a number of my clinics and we’d started getting to know each other better, I sent her a note. I told her how much I thought of her and how much our friendship meant to me. I also told Mary that I didn’t want to take her money for the clinic because I knew how hard it was to come by. I found out years later that she had been mowing lawns to come to my clinics.

Buck and Mary.

Mary called me the night she received the note and thanked me. She told me that the note made her cry. Her marriage had been an unhappy one, she had two young girls, and she didn’t know what to do.

I told her, “Mary, I want to be with you more than anyone else in the whole world.”

We started spending hours together, talking and getting to know each other. Mary knew quite a bit about me even before we’d met because I had a public life. She’d heard about Adrian and some of the things I’d fought through, but as we got to know each other better and began to trust each other, I shared with her things about myself that I normally don’t share with anybody. Because I spend a lot of time talking into a microphone, people assume that it’s not easy to hurt my feelings. It is. I’m just as sensitive as the next person, but it’s hard for people to see that in my line of work.

I didn’t say anything about Mary to my friends in Montana yet, but I did tell my foster mom about her. I told Betsy how much it meant to me to know this person, and I asked her to pray for me that one day we would be together because Mary was the person I always wanted to be with.

The turning point in our relationship came when I put on a clinic at the Pass Creek Ranch outside Parkman, Wyoming.

The students and I were all staying at a little guest house on the ranch. One night I ran out of chewing tobacco (I still had that unsavory habit), and I was headed for the Parkman Bar on the border of the Crow Indian Reservation to buy

some. Mary, who was there with her sister Mindy, said she wanted to ride along with me.

As soon as we got into the truck, Mary asked in her direct way, “So, Buck, what are we going to do about this?”

I blurted out, “You could spend the rest of your life with me, and then it wouldn’t be a problem. I’ve loved you for a long time, Mary.”

She looked at me for a moment, then she smiled and said, “Me, too.”

It was all that needed to be said. I don’t know if the Parkman Bar was five miles away or five hundred. The moment was forever.

After we got back to the ranch, we walked out to check on the horses. Until that point, we had never even held hands. But there in the Wyoming moonlight, with the world spinning around us, we held each other and kissed.

The divorce wasn’t particularly friendly when it came, but it wasn’t as bad as some. Even though I think Rob respected me, it was hard on him, and it was an adjustment for Kristin and Lauren. They were five and seven at the time, and at first they were confused that their mother wanted to be with me instead of their dad. She had always been a wonderful mother, and the girls knew she loved them, but it wasn’t easy for them, either.

Mary came out to Montana once or twice a month and stayed with me at Indian Creek in the Madison Valley. We spent most of the rest of the time on the phone. Our phone bills were close to the national debt.

I proposed while we were sitting on a bridge over Indian Creek in Ennis, Montana, where I was doing a clinic. Mary was again direct. She asked, “What do you intend to do about this?” She meant our relationship.

I replied, “I intend to spend the rest of my life with you.”

That is how it happened, on a summer evening on the Madison River, under a moonlit sky … the whole nine yards.

Mary introduced me to her girls over the July Fourth holiday in Jackson Hole. We rode the gondola up to the top of the Tetons—Kristin called it the gondelo. I felt strange at first, because I didn’t know anything about children. All I knew was about being single, but we had a lot of fun.

I had met her parents, Bill and Lorraine Bower, in Boulder a few months after we started going out. Bill had been a fairly well-known aviator during World War II. He was one of Jimmy Doolittle’s raiders flying B-25s, and he was part of the raid on Tokyo that was America’s response to Pearl Harbor. We got along just fine.

Her close friends were all for us, and so were her brothers Bill and Jimmy. Mindy was excited that we were going to be brother and sister-in-law, but some of Mary’s other friends probably thought she’d lost her mind. She was a beautiful model who had been around some fairly influential people. She knew just about everybody in Boulder, and here she was running off with a cowboy. I’m sure they were shocked, but Mary and I were so consumed with love for each other that, quite honestly, neither one of us gave a damn what anybody thought. If they couldn’t accept what we had decided

to do with our lives, then they weren’t really our friends after all.

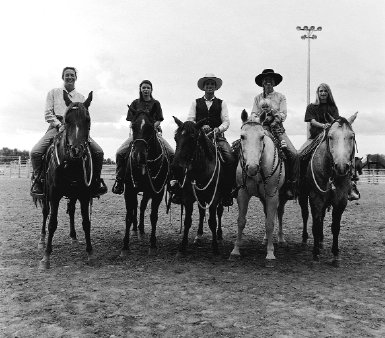

Buck, center, with some of the women in his life. From left: Mary’s sister Mindy Bower—a superb horsewoman—Mary’s daughter Lauren, Mary holding daughter Reata, and Mary’s daughter Kristin.

Mary and I were married July 6, 1992, in an outdoor ceremony at my foster parents’ ranch. Mary’s girls, her folks, and my foster mother, Betsy, were there, along with most of our closest friends. They had seen us go through some hard times, and they were thrilled for us. They seemed to feel we were getting the happy ending that we’d both been waiting for.

Kristin and Lauren were flower girls. Instead of having a specific best man and maid or matron of honor, we wanted all our friends and loved ones to play that part. Preacher Dave conducted the ceremony. As it turned out, we were the last couple he married. Not long after our wedding, he quit being a preacher and moved down to Oklahoma where he started selling mobile homes.

We lived around Bozeman for the first couple of years after we were married. We bought a house on five acres outside of town and kept several horses. I was busy doing clinics, and at first Mary found having me on the road as much as I was somewhat difficult. She’s learned to handle it pretty well since, but maybe that’s because a little bit of me goes a long way.

I began learning how to be a stepdad. Kids have a forgiveness for their real parents that they don’t have for stepparents. That means there are two different playbooks, two different sets of rules. Kids are almost looking for you to become the wicked stepfather or stepmother. That validates situations so that kids will have a scapegoat, which gives them a license to misbehave.

My primary object was to become friends with Lauren and Kristin. That’s how I learned that you pick your battles more carefully, and there are times you have to let go. Things have worked out well at our house: the girls are straight-A students and model citizens.

That goes back to what I’ve said: whether you’re dealing with a kid or an adult or a horse, treat them the way you’d like them to be, not the way they are now.

I taught the girls to ride, and Mary and I rode with them some, but they never really got into horses. Their real passion has always been schoolwork, which is a full-time job. I’m really proud of them, and I love them as I do my own daughter, Reata.

Mary got pregnant in the summer of 1993, the year we acquired the Houlihan Ranch in December. We had looked at some other places, but Mary liked the country around Sheridan, Wyoming. We heard that the ranch was available when I was doing a clinic in North Carolina. The property was a thousand acres of grassland and rolling hills, and when I got a descriptive package from the Realtor handling the sale, it looked like a good deal. Worried that the ranch would be sold by the time I got back, I made an offer sight unseen. Buying property that way can be risky, but it turned out to be one of the best decisions I ever made.

The house was old, but we remodeled it according to our tastes. I built corrals and a lot of new fencing myself, and the work I did on

The Horse Whisperer

helped pay for an indoor arena so that I’ve got a place to ride in the winter. That makes a real difference when the snow is coming in sideways at seventy miles an hour.

Our newborn daughter was named Reata, which in Spanish means a rawhide rope “of great strength”; Mary and I loved the sound of the word. Reata was born on March 30, 1994. I was in Malibu, California, doing a clinic. I had arranged to take time off so I could be present when the baby came, but Mary delivered a week early, and I just

couldn’t get home fast enough. I’ll be sorry for the rest of my life that I wasn’t there to see her birth.

It’s generally accepted that if you’re in the pattern of being abused by one or both parents, that’s what you’re going to do when you grow up. I don’t agree. I believe the deciding factor all boils down to free will. People have the choice. Self-discipline prevents that streak from coming out. You need to be vigilant to guard against a slow growth in the wrong direction. You need to be cognizant of how you behave toward your wife and children. Not a day goes by when you don’t think about how you want to be and how you

don’t

want to be. It’s always in the back of your mind, a burden that you carry.

Mary runs the ranch when I’m on the road doing clinics. We keep approximately forty horses and, depending on the summer grass, we run anywhere from one hundred to six or seven hundred steers. We ship in the fall, and Mary can do it all. She’s a good hand and resourceful, too. She takes care of the horses; she moves the cattle when it’s time to change pastures; and when there’s a tractor job that needs doing, she jumps on and does it. When I’m at home, we work together; but when I’m on the road, she’s on her own. It’s like the old saying goes: “You never want to have a bigger ranch than what your wife can run.”