Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors (32 page)

Read Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors Online

Authors: Ann Rule

Tags: #True Crime, #Nook, #Retai, #Fiction

Broken chain where the chandelier hanging over the foyer—two floors down—snapped or was cut and Max fell.

Landing where Max fell. Looking down to the foyer. Max may have been going too fast on his scooter. It was found beside him two floors below.

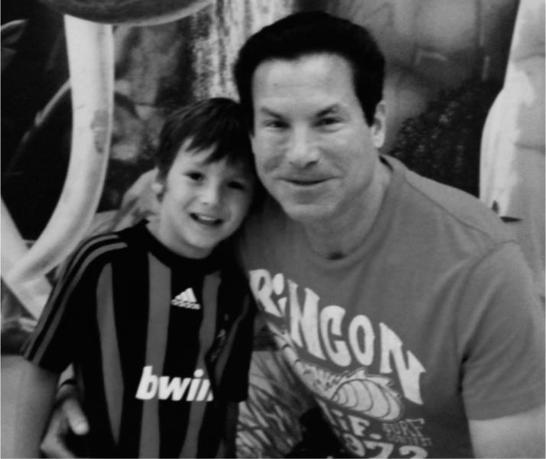

Max and Jonah, father and son, posing together.

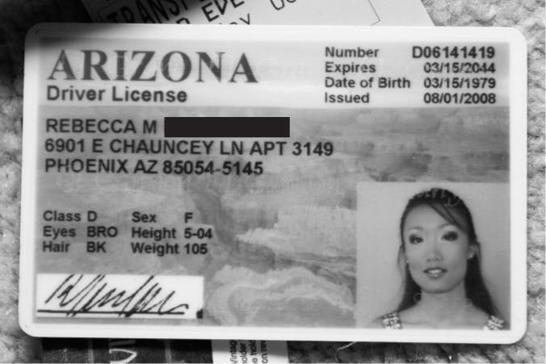

Becky Zahau’s driver’s license from Arizona, where she worked as an ophthalmologist’s surgical assistant.

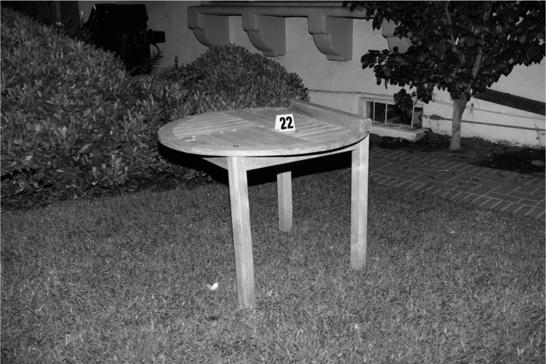

Table with broken leg. Adam said he pushed it over beneath where Becky was hanging and managed to cut her down.

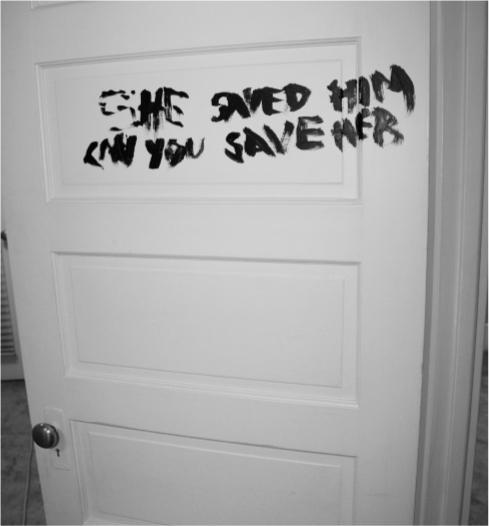

A cryptic message painted on the outside of the door to Becky Zahau’s office/spare room. SHE SAVED HIM CAN YOU SAVE HER. No one ever discovered who wrote it or what it meant.

A reddish-orange towrope for waterskiing tied to the white iron frame of the bed in Becky’s office. Note paintbrush and criminalist’s marker.

The towrope stretched from the white iron bed leg, across the floor, over the railing, knocking down a chair on the way. Did Becky Zahau tie herself up with it and deliberately plunge over the high wrought iron railing? Was she even up there in her last moments of life?

DOUBLE DEATH

FOR THE KIND

PHILANTHROPISTS

If ever a man deserved to spend his retirement years in peace and comfort, it was eighty-five-year-old Burle D. Bramhall. Certainly the old man was wealthy, and his fifty-five-year marriage to his one sweetheart, Olive, eighty-three, was as idyllic as it had been when they first took their wedding vows. Their sumptuous home in one of Seattle’s richest and oldest neighborhoods—Windermere—was just right for them. The Bramhalls lived the kind of retirement that anyone might aspire to.

Nobody who knew Burle Bramhall resented his good fortune, however, for his whole life had been one of service to others and philanthropy.

Almost ninety years ago, Bramhall was a vigorous man in his twenties. During World War I, he worked with the American Red Cross, and he managed to shepherd 783 youngsters out of Siberia for reunions with their families. Like a pied piper, he led the little ones from country to country until they were once again safe in their parents’ arms.

In 1973, when they were over eighty, Burle and Olive were guests of the Soviet Union. There they were reunited with more than two hundred of those children Burle had saved. The “children” had long since grown to late middle age themselves. In the years after that joyous meeting, the Bramhalls’ mailbox was always full of letters from these old friends who never forgot what he had done for them. He always found time to write back to those he had rescued, and his small study was crowded with mementoes they sent him.

He and Olive had never been blessed with children of their own, but they felt the children from Siberia who called him “Godfather” were somehow theirs, too.

* * *

For all of his long life, Burle Bramhall had been a consummate businessman. His accounting studies at the University of Oregon were interrupted by his Red Cross services in World War I, but, on his return to Seattle, he finished his education and went to work handling investments for the Marine National Bank. There he met the man who would be his partner for more than thirty years in the investment firm of Bramhall & Stein.

During World War II, Bramhall took a leave of absence and went to Paris and London to work with health and welfare agencies geared to serve the survivors of the second great war, and once more he immersed himself in helping displaced persons. He was approaching fifty then, but it didn’t matter.

Although his partner retired in 1969, Burle Bramhall never really did. Right up until the end of his life, he was associated with Blyth & Company, rated then as the nation’s largest investment house not tied to the New York Stock Exchange.

Burle always tempered a good business head with concern for those who had nothing. He felt grateful that he had been given—and earned—much, and he believed he owed something back.

And Olive felt the same way. The elderly couple were still having a lot of fun in their eighties. Their neighbors in Windermere often chuckled to see them all dressed up and stepping out for the evening. Their age slowed them down a little, but even so, they were considered the “night owls” of the neighborhood, driving out grandly with Burle behind the wheel of his polished 1963 Mercedes. The tall old man was a little stoop-shouldered now, but he still treated the petite Olive with all the courtliness he had used when they were first married.

When the Bramhalls’ lights were on late on the warm summer night of Wednesday, August 2, 1978, no one thought anything of it; neighbors figured Burle and Olive were watching television a little later than they usually did.

It was sometime after midnight on August 3 when the 911 emergency line at Seattle police headquarters rang and Operator 63 picked up the receiver. The conversation was terse, but also frightening.

“911 Operator 63.”

“Yes . . . I would like to get connected to the police . . .”

“This is the police department.”

“Okay . . . there was a murder at 6647.”

“When was this?”

“I don’t know.”

“There was a murder?”

“Yeah . . . two of them.”

“ . . . 6647 Windermere Way . . .”

“Yes.”

Before the operator could ask any further questions, the line went dead. The caller was a man who had no discernible accent, and that was all the operator could say about him. He jotted down the information and passed it to the radio dispatcher.

The first officers dispatched from the Wallingford Precinct in Seattle’s north station were Gordon Van Rooy, F. R. Solis, and Dale Eggers, sent to check on a “possible homicide.”

They turned into a divided private lane that led to several large homes and pulled up in front of the two-story L-shaped house marked

BRAMHALL

.

Solis covered the back while Van Rooy and Eggers approached from the front. The front door was standing open while the screen door was closed; the two officers could see the very dim light of a fluorescent grow light over a planter just inside. They could also see that a sliding glass door to what seemed to be a den was standing open, and the TV inside was still on, with only the test pattern on the screen.