Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors (39 page)

Read Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors Online

Authors: Ann Rule

Tags: #True Crime, #Nook, #Retai, #Fiction

But no one mentioned it.

When Rodger Peck applied for a job at the University Towers, he had given a job reference from St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tacoma that indicated he was a paramedic. In truth, he had been only an orderly.

Marshal 5’s arson investigators tried to follow the trail back to Rodger Peck’s life before he hired on at the Towers. He had left his St. Joseph Hospital job for unknown reasons. He wasn’t fired; he had simply walked away from that job after only three months.

Before his last job in Tacoma, Peck had worked as an orderly in a hospital in Fresno, California. Fresno police had no record on the guard beyond a current traffic warrant.

And suddenly it was as if he hadn’t lived at all before that. They wondered if he had used different aliases.

All of the fires in the University Towers had been set in the same fashion; they weren’t sophisticated. The arsonist had held flames—matches, probably—to combustibles that were easy to burn. Rodger Peck had discovered them all. In the room fire on March 6, he had seemingly known exactly where to find the fire. He claimed that smoke had come from beneath the door of room 904, and that the door was hot, yet the manager with him said there was no smoke, and the door wasn’t even warm.

The investigators found there couldn’t have been enough flame involvement at the time of discovery to send smoke through the door cracks. Still, Peck had turned immediately toward the slight flickering of flames as he entered the room.

How had he known so much?

In the major fire of March 11, there were several factors that didn’t fit. Peck claimed to have been in the lobby at 11:30, but Babani

knew

he wasn’t there. Babani had looked around the lobby for Peck in vain because he was very nervous about the strange man in the cutout shoes. The bearded man could not have set the fire. Babani had had him in sight during the crucial time, except for the few minutes when he went down to the cocktail lounge for change. The fire had been started by someone above the lobby, in the mezzanine.

Peck’s excuse for his absence was, of course, that he was hiding “around the corner” to observe the peculiar visitor.

When Peck went to check out the strange noises in the mezzanine, he claimed he couldn’t open the door above the center staircase. He said it was locked. It was not locked. Seattle police officer Hanna was able to turn the knob easily a few moments later.

Peck said he’d taken the elevator to the mezzanine. He hadn’t—or Babani would have seen him.

Rodger Peck told Officer Viegas that there was a “ball of fire” in the mezzanine. But when Hanna opened the “locked door” he had seen widely separated areas of flames, as if the fire had been started in several spots.

There were approximately twenty minutes when Rodger Peck could not be accounted for. He claimed to have checked the mezzanine at 11:30 and found it normal. The fire had to have started before then to reach the intensity it had when Peck “discovered” it shortly after midnight. His own log put him in the vicinity of the fire in room 1109 when it started.

* * *

Rodger Peck lost his job with the security guard agency, but he was a man full of pride. He pretended to the arson investigators that he was merely waiting reassignment. He also became aware that a stakeout had been placed on his apartment, but he gave no evidence that he was concerned. He called Inspector Fowler on March 24 to ask if there had been any progress on the investigation. When Fowler suggested that Peck take a polygraph, he changed the subject as if he hadn’t heard.

After more conversations with the arson investigators, Peck finally agreed to come into the Marshal 5 offices and talk to Inspector Jack Hickam. He didn’t object to having the interview taped, and actually seemed at ease during the long discussion. The former security guard had easy explanations for everything. He went into great detail about the attack on Bernadette Casey by the unknown man in the blue uniform, pointing out frequently that it could not have been him.

Peck explained how he made his rounds, sometimes taking the stairways, sometimes the elevators. He didn’t think it was unusual that all the arson and assault incidents had taken place on the nights he was on duty.

Jack Hickam was a master at interrogation. He had a friendly face and a big grin, and by the time suspects realized that he’d led them down the garden path, trapping them in their own lies, it was too late.

But Rodger Peck wasn’t fazed by Hickam’s approach. Even as Hickam pointed out all the discrepancies in Peck’s version of his actions on the nights in question, Peck continued to insist that he had just seemed to know where the fires were.

“Is there someone mad at you?” Inspector Hickam asked easily.

“I hope not. I hope I don’t have an enemy within three thousand miles of here.”

“Well,” Hickam continued, “I mean it looks like maybe you are finding an awful lot of stuff happening when you are there. Or is there someone mad at you who is trying to make you look bad?”

“Not that I know of. I figured the only reason I find it is because I am there more than the rest of them, but everything has happened when I am there, except that they received one bomb threat when I wasn’t there. That should be in the report.”

Peck fell easily into the role of an innocent man. He added more and more details that no one but the arsonist should have known. He professed willingness, at first, to take a lie detector test, but then seemed concerned that secrets of his personal life would be revealed.

Hickam assured him that only questions about the fires would be asked. They didn’t care at all about the rest of his life. Even so, the ex–security guard began to perspire.

Everything fit. Yet, as with other detectives who face frustration after frustration in bringing a circumstantial case to court, the arson unit investigators were told that, unless they could come up with physical evidence, charges against Peck would not be filed. It was a crushing blow after weeks of work. More than that, they feared a recurrence. The thought of Rodger Peck was uppermost in their minds.

But their hands were tied.

* * *

It was almost a year later, on January 29, 1976, when arson inspectors’ fears were realized.

After being fired by the security company, Rodger Peck had returned to hospital work. He was currently employed as an orderly in the Coronary Care Unit of Providence Hospital on “Pill Hill,” in downtown Seattle.

The charge nurse on duty on the evening of January 29 took a break in the lounge of 5 West. She asked Peck to answer a call light in room 506. Peck nodded obligingly and walked down the hall toward that room.

Minutes later, another attendant smelled smoke. This was, of course, an ominous situation in a ward where oxygen tanks abound. The orderly walked down the hall, sniffing the air so he could locate any fire. When he traced the smell to room 509, he was horrified to find the bed there enveloped in flames. Fortunately, there were no patients in the room at the time.

And there was a hero who rushed in to fight the fire. That hero was none other than Rodger Peck. Peck took over efficiently, extinguishing the fire on the bed before it could reach nearby oxygen tanks, and closing other patients’ doors.

Bill Hoppe was working the night shift for Marshal 5 that night, and he left the unit’s station near Pioneer Square and was up the hill at Providence in no time.

He quickly deemed the hospital bed fire as arson. He did a test burn on a similar bed linen drape and found that a handheld flame would ignite the spread in one minute and forty seconds. In talking to the nurses and orderlies on 5 West, Hoppe learned that was exactly the period when no one saw Rodger Peck before the fire bloomed in room 509.

There were no injuries, and the damage to the bedspread and mattress was no more than a hundred dollars. But it could have been a holocaust, in the worst possible location. Helpless patients, many too ill to be moved, dozens of oxygen tanks—and fire.

But again, this was a circumstantial case. No one had seen Rodger Peck in room 509 before the fire.

Although the arson team was sure that Peck was responsible for the bed fire, he was viewed as a hero around Providence Hospital’s 5 West.

On March 10, 1976, Rodger Peck was at work on 2 West. In room 230, a patient recovering from abdominal surgery waited for a doctor and nurse to remove stitches from the wound.

As the nurse headed for 230, she didn’t know that the patient had unexpectedly gone to have X-rays done.

She opened the door—and was shocked to see that the patient’s bed was entirely engulfed in flames. The nurse rushed to the bed, unaware that the patient was no longer in the room. She fought through the flames trying to find the patient and yelling “Fire!” When she finally realized that the bed was empty and the patient was nowhere in the room, she left and closed the door behind her.

The fire alarm box was in room 234 and she pulled the alarm. Then she returned to the room where the fire was.

It was no longer empty, and the fire was only flickering along charred edges of sheets and pillows.

Once again, Rodger Peck had “sensed” just where the fire was when he heard the nurse scream. That was remarkable, of course, because there had been neither flames nor smoke outside the room.

Once again, it was the hero: Rodger Peck. He had somehow reached room 230 and managed to spray the fire extinguisher over the bed until the fire was almost out.

There were many, many rooms on 2 West, but Peck had gone unerringly to room 230. He had finally run himself out of luck. This time there would be no pats on the back, no compliments on his quick thinking.

The arson investigators determined that the cause of the fire was arson. Someone had lit paper from a crossword puzzle book with a match and then held that paper to the drapes around the bed. With the fire burning fiercely, that “someone” had left the door ajar enough so that the flames could gather momentum.

No one on the floor could remember where Rodger Peck was just before the fire started. He was running true to form—he’d been the invisible man before the fire, and then the indispensable hero.

Damage was limited to the mattress, bedding, and the nurse’s call indicator. Rodger Peck was like a sniper firing wildly into a crowd, neither knowing nor caring how many might die.

This time, he had pushed his luck too far. On March 11—exactly one year to the day since the last fire at the University Towers Hotel—Inspector Fowler and Seattle police detective Bill Berg arrested Rodger Peck and booked him on five counts of arson. His bail was set at ten thousand dollars.

He went on trial May 25. It is a difficult task to convict someone on arson charges. Peck’s first trial resulted in a hung jury. He remained in custody until his second trial on September 3.

By now, Rodger Peck had grown cocky and he seemed to enjoy his time on the witness stand. He was the center of attention, something he had long aspired to. Perhaps he simply could not resist talking about fire. As his defense attorney turned pale and the jury members exchanged glances, Peck regaled the jurors with accounts of the many fires he had witnessed. As he warmed to the subject, he seemed at ease in the witness chair; he apparently saw himself as the definitive expert on fire.

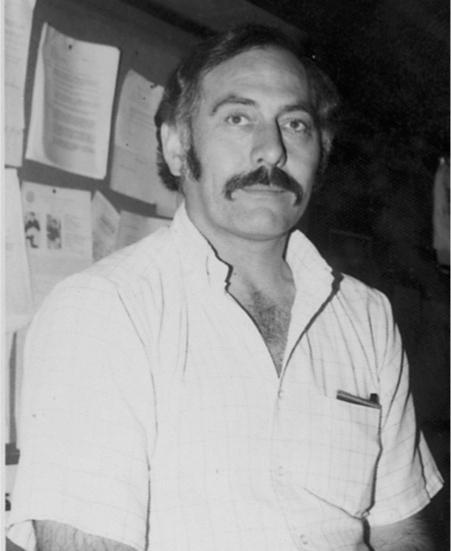

He was so caught up with the sound of his own voice that he convicted himself. After only two hours of deliberation, the jury found Peck guilty on four of the arson counts. On September 27, Rodger Leon Peck, twenty-nine, alias Rodger Bridges alias Rodger Williams alias Leon Rodgers, was sentenced to four life sentences—to run concurrently.

With that sentencing, the Seattle Fire Department’s Marshal 5 team heaved a sigh of relief. Peck had backed himself into a corner. They were always sure that this serial arsonist would be arrested and convicted one day.

But they feared that many innocents might die before that happened.

Rodger Peck was elusive, but he was not particularly clever. His case is an example of how difficult it is for detectives and prosecutors to bring an arsonist to trial. There are many inequities in the system. But with the advent of computers, Internet communication, and security cameras, fire-starters are being tracked and identified much more effectively than ever before.

Rodger Peck has served his sentence and hasn’t come to the attention of the Seattle Fire Department’s arson unit since he was paroled. But any potential arsonist in the city of Seattle should be forewarned that he is facing one of the most sophisticated and efficient fire departments in the world. Inevitably, all arsonists leave patterns, with the same MOs used again and again.

They also leave behind ashes that are full of evidence to an experienced arson investigator.

FIRE!

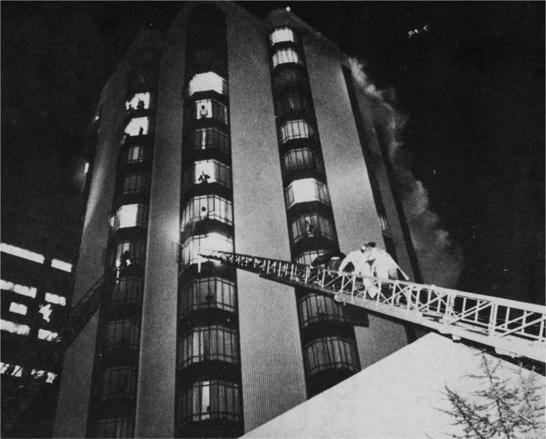

The University Towers Hotel’s fire belches smoke and flames as Seattle firefighters scale ladders on two sides of the building, trying to reach anxious guests who stand in their windows. Arson investigators soon found that this was not an accidental fire, and they questioned a number of possible suspects.