Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors (53 page)

Read Fatal Friends, Deadly Neighbors Online

Authors: Ann Rule

Tags: #True Crime, #Nook, #Retai, #Fiction

With his background of violence, Mark Rivenburgh

was

a natural suspect. That was a given. However, he didn’t appear nervous about being questioned. He didn’t ask to leave the interview room, although he would later claim on an appeal that he had been subjected to “custodial interrogation” without ever being read his Miranda rights.

The New York police detectives questioned him off and on until 6:30

A.M.

At that time they asked him if he would tell them again about his lost wallet. They had noticed that he had bulges in his pants pockets, and they wondered if one of them held his wallet.

Agreeably, Mark Rivenburgh emptied his pockets. There was no wallet, but he was carrying a pouch of .38-caliber bullets, something considerably more incriminating than a lie about his wallet.

At this point he was arrested. To be sure he understood, the interviewers once again read the Miranda warnings. He said he understood he could stop questioning, he could call an attorney, and that anything he said from this point on might be used against him in any court procedure. The New York State troopers searched him more thoroughly. As they frisked him, they felt a hard lump in the small of his back. When they lifted his shirt, they uncovered a loaded .38-caliber handgun strapped to the back of his waistband.

It was somewhat unnerving for them to realize he had been armed and carrying about forty rounds of ammunition all the time they were questioning him.

Mark Rivenburgh admitted that he’d purchased the gun several years earlier, but he said he had no choice.

“It goes everywhere with me,” he said firmly.

“How about your wallet?”

“That was a lie. I didn’t lose it.”

When they lifted the cuffs of his trousers, the state police interrogators saw that the onetime Ranger’s socks had partially dried dark stains on them. Criminalists later identified those as blood that had the exact DNA pattern of Jeffery Hurd.

The bullets removed from Hurd’s body proved to have been fired from the .38-caliber revolver that Mark Rivenburgh always carried. There was no question that Rivenburgh had shot his neighbor, probably in cold blood.

But why? What was his motivation to kill Jeffery Hurd? Whether it was true or only Rivenburgh’s imagination, he had been voluble as he complained to neighbors—as he now told state police detectives—that he resented Hurd. He claimed that the physicist had taken certain items from his house without any authorization to do so.

Most physicists earn well over a hundred thousand dollars a year. It seemed unlikely that a man who had such a well-paying and respected job as Hurd would have any need or motive to steal from Rivenburgh.

This time, Mark Rivenburgh did not remain free on bail. He was held in the Ulster County Jail in Kingston, awaiting trial for the murder of Jeffery Hurd.

There were many delays. Almost a year later, on the first weekend in May 1999, Rivenburgh was three days away from his pretrial hearing. Everything seemed normal as he strolled out into “the Yard” at the county jail, just as he always did for his weekly one-hour exercise session. He carried a wooden “sit-up” board that some inmates put up against the twelve-foot concrete walls to make that exercise tougher as they worked to maintain “washboard abs.”

Mark Rivenburgh was in excellent physical shape. Even though he was forty-seven, he prided himself on staying in “Ranger condition.” At 10:45 that particular Saturday morning, however, he had another use for the board. Before corrections officers could stop him, he used it to get up and over the wall in less than a minute.

Even the many layers of razor wire didn’t slow him down. His next hurdle was an eighteen-foot jump off a roof. He could hear guards shouting at him to stop, but he leapt anyway. Encountering two corrections officers on the ground, he fought with them briefly before he managed to break free again.

A pond lay ahead of him, and he plunged in, swimming strongly for the other side. But the officers could swim as well as he could and the water chase began. They caught up with Rivenburgh on the other side.

Finally, he gave up.

On top of the other crimes he was charged with, the former Ranger now faced charges of first-degree escape, and he was forbidden to leave his cell—except, of course, to attend his trial for murder.

Although his lawyer warned him against testifying—as the majority of defense attorneys do—Mark Rivenburgh insisted on taking the witness stand. He told the jury that he had good reason to carry a gun because a certain underground group had threatened him and made him fear for his life. It was possible he was attempting to raise questions about his sanity under the M’Naghten Rule. If that was the case, it didn’t work.

There had been a paucity of physical evidence in the crimes against Kit Spencer and Rose Fairless in 1978. There were no DNA matches then, but this time the prosecution team was armed with both DNA evidence and ballistics results that could not be explained away.

On Thursday, June 24, 1999, an Ulster County jury deliberated for only four hours before they signaled that they had reached a verdict in the murder trial of Mark Rivenburgh for the shooting of Jeffery Hurd. They found him guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree criminal possession of a weapon, and several other charges, not the least of which was first-degree escape. He was sentenced to consecutive terms of twenty-five years to life on the murder charge and seven years on the weapons charge. That meant thirty-two years in prison.

Mark Rivenburgh would be almost eighty years old before he might be considered for parole.

He appealed his conviction in 2003, and on November 13, the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, concurred with the lower court. They did, however, find some merit in Rivenburgh’s objection to the Ulster County Court’s allowing a state police trooper to testify about a series of unsolved crimes—rapes and robberies—in an adjacent county. Although the jury didn’t know about his sexual crimes in Washington State, there was, the Supreme Court said, a possible inference by the state that Rivenburgh was a prime suspect in those more recent cases.

Perhaps he was. Perhaps there was another sexual stalker who used MOs so similar to Rivenburgh’s 1978 assaults.

At any rate, his appeal of the conviction for Jeffery Hurd’s murder was denied.

Mark Rivenburgh remains in prison as this is written. He is now sixty years old. One has to wonder why a young soldier, chosen among the “cream of the crop,” veered so far off what he seemed to be. His superiors deemed him an outstanding army Ranger, but he threw it all away in his obsession with sexual and murderous violence.

TERROR ON A MOUNTAIN TRAIL

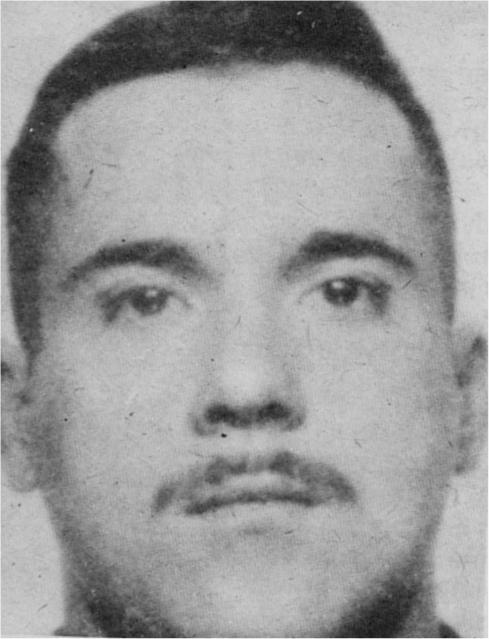

Mark Leslie Rivenburgh, twenty-nine, an army Ranger whose commanders found him exceptionally proficient and dedicated. This is a booking photo after he was arrested for sexually attacking two young female hikers on Washington State’s Mount Rainier. (

Police file

)

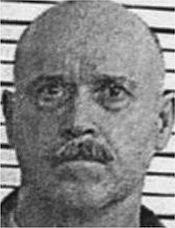

Mark Leslie Rivenburgh at sixty. After his release from prison on sexual offense charges, he reoffended, this time committing murder. (

Prison file

)

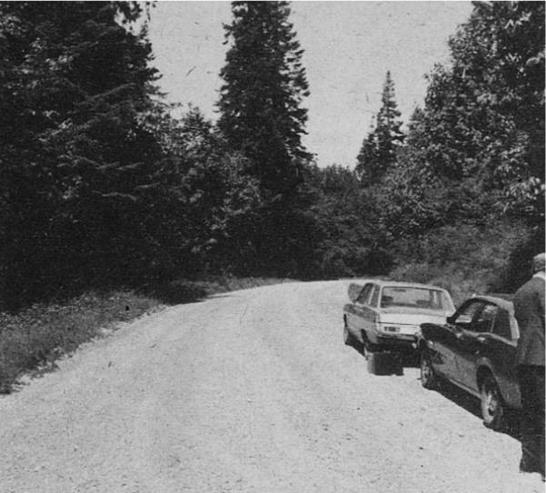

All the entrances to Mount Rainier National Park were blocked in an attempt to trap a wanted sex offender inside the park. (

Police file

)

NO ONE KNOWS

WHERE WENDY IS

I wrote another case that involved the military complex that stretches south from Tacoma, Washington. It is very different from the Mark Rivenburgh cases, and far more likely to break our hearts. Still, this is a cautionary tale that every parent or caregiver should read. We don’t always know the people who live or spend time in close proximity to us. And, too often, we trust someone we shouldn’t.

Until October 2010, Fort Lewis, McChord Air Force Base, and Madigan Military Hospital were separate entities, but it was inevitable that they would one day merge. They have become one of twelve joint bases in the world, known now as JBLM (Joint Base Lewis-McChord).

This joint base is a community unto itself, the second-largest military installation in the country, with dozens of divisions, each with its own specifications and duties. As with every huge military base, businesses have proliferated nearby. Along Interstate 5, the freeway that runs from the Canadian border to Tijuana, Mexico, there are massage parlors, taverns, tawdry nightspots, dry cleaners for uniforms, trailer parks, loan and check-cashing companies, and myriad other enterprises abounding there, all anxious to help servicemen spend their paychecks. Neon signs flash for twenty-four hours a day, luring them in.

For many service families, however, the military bases are as homey as any street in the Midwest. Family housing neighborhoods stretch out, row upon row of almost identical houses. They can be pretty basic, but residents grow gardens and add special touches that make their houses distinctive. As rank escalates, the homes become bigger, and farther apart. Majors, colonels, and up are allotted sumptuous Colonials with spreading lawns.

But there are facilities that make off-duty life better for all men and women serving our country. There are theaters, swimming pools, the BX, and other commissaries, medical facilities—everything a family needs right on the bases. The honky-tonks along the freeway are a world apart, shut off by miles of fences along the freeway.

And the joint base is almost impossible to enter for someone who has no business there. Guards man gates at all times, and visitors have to have more than adequate identification.

JBLM is “good duty,” and military families who live there take advantage of the Northwest’s many recreational opportunities, including camping, hiking, skiing, sledding, and deepwater fishing on the Pacific Ocean down in Grays Harbor County.

It has always been so, and on Saturday, July 10, 1976, a staff sergeant took his family out on a strawberry-picking expedition. He had spent the earlier part of the day working on a picnic table in the backyard of the duplex where they lived, a project that excited his nine-year-old stepdaughter, Wendy Ann Smith, and her six-year-old brother. It seems almost impossible to realize that Wendy would be forty-five years old today. If only she hadn’t trusted someone. If only she could have seen behind his friendly smile. But nine-year-olds aren’t especially skilled at detecting evil.

The sun was low in the sky at eight that evening when the berry-picking group returned to the duplex. The children were tired and dirty after their hours playing between the strawberry rows, and Wendy’s mother went immediately to run a bath for the youngsters. As the water splattered into the tub, she remembered that she’d left her favorite blue sweater in the car. She asked Wendy to run out and get it.

“While you’re out there, honey,” she added, “get the litter bag and empty it.”

Wendy skipped off to the van. She retrieved her mother’s sweater and emptied the car trash bag into a garbage can outside the duplex. Wendy’s aunt, visiting from Arizona, was watching the beautiful blond child. But Wendy didn’t come in the house. Instead, her aunt saw Wendy look up as if she recognized someone, someone just out of the aunt’s range of vision.