Fatal Vows (15 page)

Authors: Joseph Hosey

Morphey then tried to give him the money Peterson paid him, Martineck said, but he would not take it and doesn’t know how much it was.

The day after Stacy disappeared, Morphey tried to kill himself because “he was just afraid of his family’s life,” Martineck said. Afraid for his family’s life, perhaps, envisioning the aftermath of whatever Drew Peterson had drawn him into. Bolingbrook Fire Department logs show an 11 p.m., October 29, report of Morphey overdosing on sleeping pills.

An interview with Martineck later aired on the prime-time news program

Dateline

NBC. On this show, he said Morphey told him, “I went with Drew to his house. He asked me to help him move something, and I said, ‘Yeah.’

“I go, ‘That’s understood, but what do you mean, Stacy?’” Martineck said. “And he goes, ‘Well, we lifted a blue container out of—out of his room down into his truck.’ ‘Well, how do you know it’s Stacy?’ ‘It was warm.’ And the way he said ‘warm,’ it’s like it was warm.”

Martineck says Peterson even provided Morphey with a motive.

“Because, like, from what Tom said, Stacy was filing for a divorce,” he explained. “And Drew had to be out and apparently Drew wanted everything to himself.”

When questioned about his statements on network television, Martineck refused to elaborate.

After Morphey overdosed on pills and alcohol and was taken to the hospital, he received a visit from his brother-in-law.

“Yeah, I went to see him in the hospital,” Peterson recalled. “I think it was the next day.”

From the hospital, Morphey went somewhere that wasn’t his home.

His live-in girlfriend, Sheryl Alcox, told the

Chicago Sun-Times

a month after Stacy had vanished that Morphey had not been home in “several” weeks.

“He’s in therapy,” Alcox explained, and in the months that followed, he was nowhere to be found on Thistle Drive.

If Martineck’s story about Morphey believing he unwittingly helped carry a container holding Stacy’s body was anywhere close to being on the money, the man’s conscience must have been consuming him. But then various media outlets reported stories about Morphey doing much more than helping carry a container. If true, Morphey no longer seemed quite so unwitting.

Peterson dismissed all of it: from his paying off Morphey to help him get rid of Stacy, to the very existence of the blue barrel he supposedly carted out of his home the night Stacy was last seen.

“He was one of those guys who was needy all the time, like Mims,” Peterson said of Morphey, comparing his stepbrother to Ric Mims, the former friend and fellow cable-television installer who had bunkered down with Peterson and his children in their home in the first few days after Stacy’s disappearance, but then turned on his old pal, selling a scurrilous story to the

National Enquirer

, reportedly for thousands of dollars.

“I helped him out,” Peterson said of Morphey, sounding, as he did immediately after Stacy disappeared, like a grieved, betrayed benefactor. “I gave him furniture.” At the time Stacy disappeared, he was also trying to line up a job for Morphey at the local Meijer department store.

“To know him is to love him, because he’s such an idiot,” Peterson has said of his stepbrother.

“He’s a nice lovable guy,” Peterson said, “but he’s fucked up all the time.”

Morphey paid back this kindness, if Martineck is to be believed, by shooting his mouth off and all but accusing Peterson of killing his wife, stuffing her in a barrel, and sneaking her body out of the house.

“The guy definitely had mental problems,” Peterson said of his stepbrother. He has his own theory on what may have been motivating Martineck and Morphey. It was the same thing he said was motivating Mims.

“Maybe those guys were trying to get their fifteen minutes of fame,” he said.

Someone was lying, that much was clear, but was it Peterson, in his denials of moving a barrel with his stepbrother? Or was it Martineck, telling a big story in front of the television cameras? Or could it have been Morphey himself, heading over to Martineck’s door and spinning a yarn either out of a need for attention or due to something rooted in illness or delusion?

If Morphey has made it back to Thistle Drive since he was taken to the hospital at the end of October, he has not been venturing outside or answering the door. He was rumored to be in some sort of police-protected custody until he could be used to testify before the grand jury investigating the death of Kathleen Savio and disappearance of Stacy Peterson.

But his value as a witness was questionable, at least according to one police source.

The state’s attorney’s office was reluctant to put Morphey in front of the grand jury for fear his testimony would not amount to much, the source said. When it came to the night in question, Morphey was afflicted with “memory lapses,” the source said, and his recollection of helping his stepbrother carry a barrel out to the waiting GMC Denali was less than lucid.

In the months following Stacy’s disappearance, Peterson said he had not heard from his stepbrother and did not know where he had gone. In the spring of 2008, Peterson claimed he knew exactly where Morphey was: “The police are sitting on him, not to protect him; the police are sitting on him to clean him up.”

Still Peterson conceded he did not actually have any idea where it was that the police may have been “sitting” on his stepbrother.

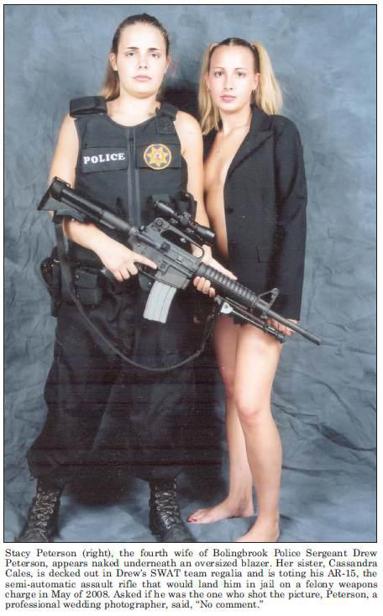

Besides, Peterson had far greater concerns—the police executing search warrant after search warrant at his home and the weekly grand jury hearings to which his family and friends were called to testify, not to mention a felony weapons charge hanging over his head—than Tom Morphey’s whereabouts. At one time, not too long ago, Peterson said he was trying to get his stepbrother a job. Now he did not even know how to find him.

But jobs—for his stepbrother or, after so many years of burning the candle at both ends, for himself—were the last thing on Peterson’s mind. He had just retired from the one he’d worked at for twenty-nine years, and he did not miss it a bit.

“Am I missing it? Not really,” Peterson said in regards to his mental state after walking away from his life as a police officer. “I have too much other stuff on my plate to worry about anything.”

And the man who worked six jobs at a time, who once had more than a hundred people on his payroll, had no strong desire to pursue gainful employment. A new job was out of the question. With his young wife missing and the police looking at him as the primary suspect, so was his love life.

“I’m not going to get another date,” he said.

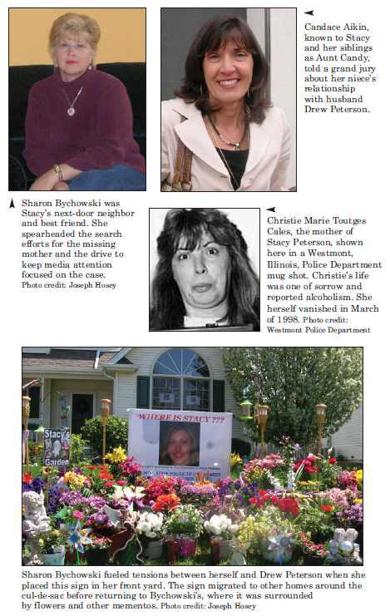

Not if his next-door neighbor Sharon Bychowski has anything to do with it. Ever since Stacy went missing, Bychowski has spearheaded efforts to search for her and keep her memory alive. She’s also vowed to tell any young woman seen venturing into Peterson’s home exactly what she suspects happened to his last wife, not to mention the one before her.

“He’ll never have a girlfriend out here that I won’t say something to,” Bychowski said.

What will Bychowski tell the next prospective Peterson love interest?

“You need to think about this. The last one died. The one before that died. You’re next.”