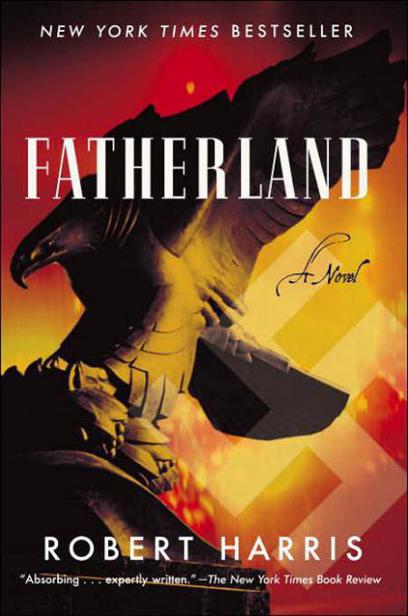

Fatherland

Authors: Robert Harris

I thank the librarian and staff of the Wiener Library in London for their help over several years.

I also thank, for their wise advice and kind support, David Rosenthal and—especially—Robyn Sisman, without whose enthusiasm this book would not have been started, let alone finished.

TO GILL

The hundred million self-confident German masters were to be brutally installed in Europe, and secured in power by a monopoly of technical civilisation and the slave-labour of a dwindling native population of neglected, diseased, illiterate

cretins,

in order that they might have leisure to buzz along infinite

Autobahnen,

admire the Strength-Through-Joy Hostel, the Party headquarters, the Military Museum and the Planetarium which their Fuehrer would have built in Linz (his new Hitleropolis), trot round local picture-galleries, and listen over their cream buns to endless recordings of

The Merry Widow

. This was to be the German Millennium, from which even the imagination was to have no means of escape.

HUGH TREVOR-ROPER

The Mind of Adolf Hitler

People sometimes say to me: "Be careful! You will have twenty years of guerrilla warfare on your hands!" I am delighted at the prospect . . . Germany will remain in a state of perpetual alertness.

ADOLF HITLER

August 29, 1942

I swear to Thee, Adolf Hitler,

As Führer and Chancellor of the German Reich,

Loyalty and Bravery.

I vow to Thee and to the superiors

Whom Thou shalt appoint

Obedience unto Death,

So help me God.

1

Thick cloud had pressed down on Berlin all night, and now it was lingering into what passed for the morning. On the city's western outskirts, plumes of rain drifted across the surface of Lake Havel like smoke.

Sky and water merged into a sheet of gray, broken only by the dark line of the opposite bank. Nothing stirred there. No lights showed.

Xavier March, homicide investigator with the Berlin

Kriminalpolizei

—the Kripo—climbed out of his Volkswagen and tilted his face to the rain. He was a connoisseur of this particular rain. He knew the taste of it, the smell of it. It was Baltic rain from the north, cold and sea-scented, tangy with salt. For an instant he was back twenty years, in the conning tower of a U-boat, slipping out of Wilhelmshaven, lights doused, into the darkness.

He looked at his watch. It was just after seven in the morning.

Drawn up on the roadside before him were three other cars. The occupants of two were asleep in the drivers' seats. The third was a patrol car of the

Ordnungspolizei

—

the Orpo, as every German called them. It was empty.

Through its open window came the crackle of static, sharp in the damp air, punctuated by jabbering bursts of speech. The revolving light on its roof lit up the forest beside the road: blue-black, blue-black, blue-black.

March looked around for the Orpo patrolmen and saw them sheltering by the lake under a dripping birch tree. Something gleamed pale in the mud at their feet. On a nearby log sat a young man in a black tracksuit, SS insignia on his breast pocket. He was hunched forward, elbows resting on his knees, hands pressed against the sides of his head—the image of misery.

March took a last draw on his cigarette and flicked it away. It fizzed and died on the wet road.

As he approached, one of the policemen raised his arm.

"Heil, Hitler!"

March ignored him and slithered down the muddy bank to inspect the corpse.

It was an old man's body—cold, fat, hairless and shockingly white. From a distance, it could have been an alabaster statue dumped in the mud. Smeared with dirt, the corpse sprawled on its back half out of the water, arms flung wide, head tilted back. One eye was screwed shut, the other squinted balefully at the filthy sky.

"Your name,

Unterwachtmeister?"

March had a soft voice. Without taking his eyes off the body, he addressed the Orpo man who had saluted.

"Ratka, Herr

Sturmbannführer.

"

Sturmbannführer was an SS title, equivalent in Wehrmacht rank to major, and Ratka—dog tired and skin soaked though he was—seemed eager to show respect. March knew his type without even looking around: three applications to transfer to the Kripo, all turned down; a dutiful wife who had produced a football team of children for the Führer; an income of 200 Reichsmarks a month. A life lived in hope.

"Well, Ratka," said March in that soft voice again. "What time was he discovered?"

"Just over an hour ago, sir. We were at the end of our shift, patrolling in Nikolassee. We took the call. Priority One. We were here in five minutes."

"Who found him?"

Ratka jerked his thumb over his shoulder.

The young man in the tracksuit rose to his feet. He could not have been more than eighteen. His hair was cropped so close the pink scalp showed through the dusting of light brown hair. March noticed how he avoided looking at the body.

"Your name?"

"SS-Schütze

Hermann Jost, sir." He spoke with a Saxon accent—nervous, uncertain, anxious to please. "From the Sepp Dietrich training academy at Schlachtensee." March knew it: a monstrosity of concrete and asphalt built in the 1950s, just south of the Havel. "I run here most mornings. It was still dark. At first I thought it was a swan," he added helplessly.

Ratka snorted, contempt on his face. An SS cadet scared of one dead old man! No wonder the war in the Urals was dragging on forever.

"Did you see anyone else, Jost?" March spoke in a kindly tone, like an uncle.

"Nobody, sir. There's a telephone booth in the picnic area, half a kilometer back. I called, then came here and waited until the police arrived. There wasn't a soul on the road."

March looked again at the body. It was very fat. Maybe 110 kilos.

"Let's get him out of the water." He turned toward the road. "Time to raise our sleeping beauties." Ratka, shifting from foot to foot in the downpour, grinned.

It was raining harder now, and the Kladow side of the lake had virtually disappeared. Water pattered on the leaves of the trees and drummed on the car roofs. There was a heavy rain-smell of corruption: rich earth and rotting vegetation. March's hair was plastered to his scalp, water trickled down the back of his neck. He did not notice. For March, every case, however routine, held—at the start, at least—the promise of adventure.

He was forty-two years old—slim, with gray hair and cool gray eyes that matched the sky. During the war, the Propaganda Ministry had invented a nickname for the men of the U-boats—the "gray wolves"—and it would have been a good name for March in one sense, for he was a determined detective. But he was not by nature a wolf, did not run with the pack, was more reliant on brain than on muscle, so his colleagues called him "the Fox" instead.

U-boat weather!

He flung open the door of the white Skoda and was hit by a gust of hot, stale air from the car heater.

"Morning, Spiedel!" He shook the police photographer's bony shoulder. 'Time to get wet." Spiedel jerked awake. He gave March a glare.

The driver's window of the other Skoda was already being wound down as March approached it. "All right, March. All right." It was SS Surgeon August Eisler, a Kripo pathologist, his voice a squeak of affronted dignity. "Save your barrack-room humor for those who appreciate it."

They gathered at the water's edge, all except Dr. Eisler, who stood apart, sheltering under an ancient black umbrella he did not offer to share. Spiedel screwed a flashbulb onto his camera and carefully planted his right foot on a lump of clay. He swore as the lake lapped over his shoe.

"Shit!"

The flash popped, freezing the scene for an instant: the white faces, the silver threads of rain, the darkness of the woods. A swan came scudding out of some nearby reeds to see what was happening and began circling a few meters away.

"Protecting her nest," said the young SS man.

"I want another here." March pointed. "And one here."

Spiedel cursed again and pulled his dripping foot out of the mud. The camera flashed twice more.

March bent down and grasped the body under the armpits. The flesh was hard, like cold rubber, and slippery.

"Help me."

The Orpo men each took an arm and together, grunting with the effort, they heaved, sliding the corpse out of the water, over the muddy bank and onto the sodden grass. As March straightened, he caught the look on Jost's face.

The old man had been wearing a pair of blue swimming trunks, which had worked their way down to his knees. In the freezing water, the genitals had shriveled to a tiny clutch of white eggs in a nest of black pubic hair.

The left foot was missing.

It had to be, thought March. This was a day when nothing would be simple. An adventure, indeed.

"Herr Doctor. Your opinion, please."

With a sigh of irritation, Eisler daintily stepped forward, removing a glove from one hand. The corpse's leg ended at the bottom of the calf. Still holding the umbrella, Eisler bent stiffly and ran his fingers around the stump.

"A propeller?" asked March. He had seen bodies dragged out of busy waterways—from the Tegelersee and the Spree in Berlin, from the Alster in Hamburg—that looked as if butchers had been at them.

"No." Eisler withdrew his hand. "An old amputation. Rather well done, in fact" He pressed hard on the chest with his fist. Muddy water gushed from the mouth and bubbled out of the nostrils. "Rigor mortis fairly advanced. Dead twelve hours. Maybe less." He pulled his glove back on.

A diesel engine rattled somewhere through the trees behind them.

"The ambulance," said Ratka. "They take their time."

March gestured to Spiedel. "Take another picture."

Looking down at the corpse, March lit a cigarette. Then he squatted on his haunches and stared into the single, open eye. He stayed that way a long while. The camera flashed again. The swan reared up, flapped her wings and turned toward the center of the lake in search of food.