Fear Drive My Feet (2 page)

Read Fear Drive My Feet Online

Authors: Peter Ryan

Plagued by âheadaches, faintness, giddiness and attacks of nose-bleeding', Ryan and

Howlett return over the mountains to the village of Chivasing, where they are betrayed

by the natives and ambushed by the Japanese. Howlett is shot; Ryan survives by burying

himself âdeep in the mud of a place where the pigs used to wallow, with only my nose

showing'. He can hear the Japanese calling out to each other,

and their feet sucking and squelching in the mud as they searched. I could not see,

so I did not know exactly how close they were, but I could feel in my ears the pressure

of their feet as they squeezed through the mud. It occurred to me that this was probably

an occasion on which one might pray, and indeed was about to start a prayer. Then

something stopped me. I said to myself so fiercely

that I seemed to be shouting under

the mud, âTo Hell with God! If I get out of this bloody mess, I'll do it by myself!'

Later, at the Bulolo base, Ryan is berated by a stock figure of military bureaucracy:

âDon't you realise it's a crime in the Army to lose your pay book?' While a battle

is fought nearby, Ryan recuperates before being flown to the coast, over âthe land

which had soaked up the sweat of two years'. He reflects on man's bravery, on patience

and endurance, and hopes it will also be learned that âwars and calamities of nature

are not the only occasions when such qualities are needed'.

The book concludes with this prose of noble plainness, but its story and the manner

of its telling have resonated for more than fifty years. Richly realised are aims

modestly stated: the depiction of war, but âon the smallest possible scale', and

âwhat happened to one manâwhat he did, and how he felt about it'.

Fear Drive My Feet

is informed by Ryan's admiration for the Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius,

to whose counsel for the control of fear, âcease to be whirled around', he paid special

notice when under aerial bombardment.

The book has two telling epigraphs. One is Erasmus's remark that âin the Military

Service, there is a busy kind of Time-Wasting.' This speaks to the long periods of

inaction that the book describesâwaiting in lonely bush camps to go into action,

recovering from malaria and the broken bones caused by falls, at the mercy of intermittent

orders and supplies. The second epigraph is from Job, 18.11: âTerrors shall make him afraid on every side, and shall drive him to his feet.' The facing

and surmounting of those terrors, mental and physical, is the matter of Peter Ryan's

bookâthe finest Australian memoir of war.

PREFACE

I WROTE THIS

book at the age of twenty-one, when the travels of 1942 and 1943 were

like the day before yesterday. Any small uncertainty â a precise date, the name

of a village headman â could be settled from dog-eared notebooks, or the tattered

sheets of old patrol reports. Flicked over in pursuit of some such bald fact, these

crumbling documents gave off the musty smell of paper which had begun its decay

in the mildews of the tropics. Many years passed before I understood: this haunting

odour, in silent eloquence, had been speaking to me just as clearly as the written

sentences now fading on the pages.Truly, a trace of Proust lurks in the least of

us.

During 1944 and 1945 I had a soft job in an Army school in the grounds of the Royal

Military College, Duntroon, teaching New Guinea pidgin English (Tok Pisin) to cadet

patrol officers. Those nights not spent in the mild dissipations of the Mess were

for reading or writing in one's room â a narrow cell furnished with a bed, a table

and a chair, all of monastic austerity. My window opened outwards towards Mount Pleasant

where, just a hundred yards away, was the tomb of General Bridges, killed on Gallipoli

as commander of our first A.I.F. Now he lay there at peace, beneath his immense bronze

funerary sword.

The notion of actually

writing a book

seemed preposterous, when it first crossed

my mind one frosty night. I had left school at sixteen for a dull job in the Victorian

public service, from which I enlisted shortly before Japan entered the war in late

1941. What possible qualification had I for authorship?

At school, my English and History master, Gordon Connell, had been a teacher of genius.

(He had, a few years earlier, taught our famous architect and writer, Robin Boyd.)

From âCactus' Connell I had learnt, at least, not even to start writing unless there

was something interesting to say; and if there was, to say it simply. He also infected

me with (no one has ever put it better than Gibbon) âthat early and invincible love

of reading which I would not exchange for the treasure of India'.

It struck me that very few soldiers of eighteen would have been sent out alone and

untrained to operate for months as best they could behind Japanese lines; that few

indeed would have passed their nineteenth and twentieth birthdays engaged in such

a pursuit. Might this be an interesting topic?

In the quiet nights of Canberra, a small and rather nervous manuscript built up.

The hard decisions for the greenhorn author were what to leave out, for a great deal

had happened besides the story told in the pages of this book: the sinking in Port

Moresby harbour of the

Macdhui

, the ship which carried me from Australia; numberless

enemy aerial bombardments; the later escape, by a matter of minutes, from sinking

by a Japanese submarine in the Gulf of Papua; the taxing walk right across New Guinea

over the notorious Bulldog Track; running supply lines of native carriers to our

troops operating behind Salamaua. This was all too much for my untried skill to tackle,

and all too much for the patience of readers. I decided to focus on a series of intelligence

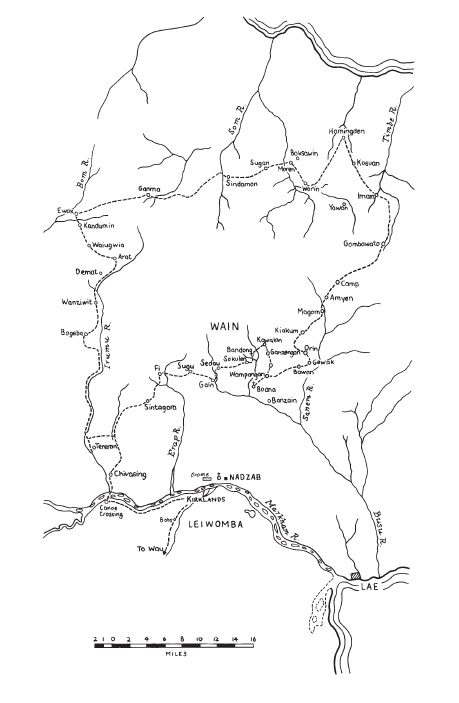

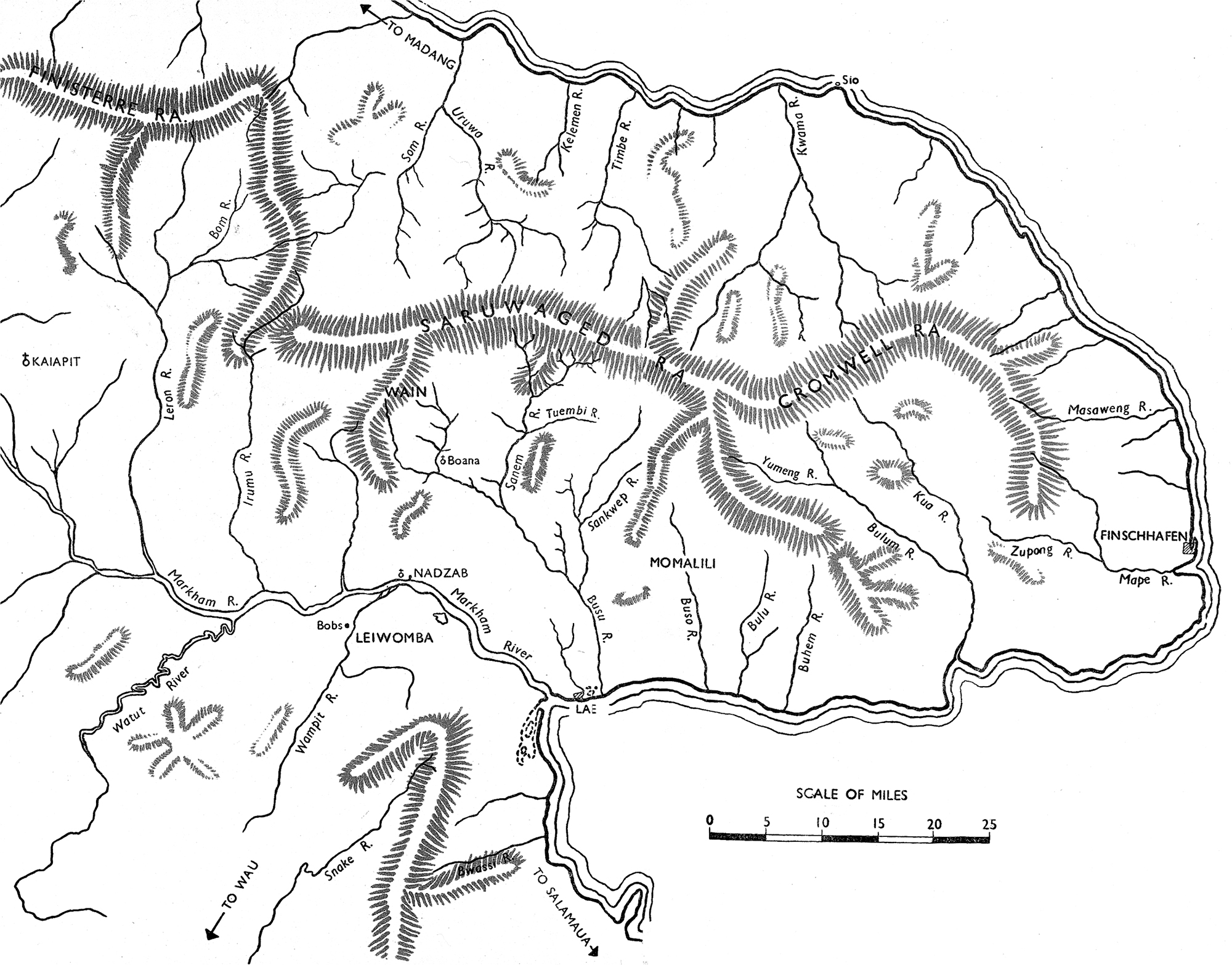

patrols all carried out in the general region of the Markham River, which enters

the sea near the then great Japanese base at Lae.

Between 1945 and 1950, three different publishing

firms read this amateur manuscript.

Two said they were keen to publish, but were eventually thwarted by post-war publishing

problems, chiefly the world shortage of paper. So the manuscript was tossed into

a cupboard at home and would still be there, but for an extraordinary chance.

In 1958, in Melbourne, we had briefly as a house guest that wonderful woman Ida Leeson,

Mitchell Librarian from 1932 to 1946. When the poet James McAuley was once asked

to define the meaning of the noun âsecret', he replied that a secret was âsomething

very carefully hidden so that it could be discovered by Ida Leeson'.

Doubtless trawling our cupboards for any secret which might lie there awaiting her,

she found my abandoned script and, without my knowledge, read it. She announced that

she was taking it back with her to Sydney, to discuss it with Angus & Robertson.

Ten days later came the exciting telegram: âAngus & Robertson will publish stop

love Ida'.

So I was to be an author! Just like that! A&R's superb chief editor Beatrice

Davis excised scores of absurdly superfluous commas, but made no changes of substance.

Not a word has been altered since

. Fear Drive My Feet

appeared in hardback in November

1959, and Lance-Corporal Kari (promoted now to resplendent Sergeant-Major) came down

from Port Moresby for the launching. All the reviewers were very kind, Douglas Stewart

of the

Bulletin

devoting to the book the whole of his prestigious Red Page.

Gwyn James, manager of Melbourne University Press, took it up for his new series

of Melbourne Paperbacks in 1960, and it was twice more (in a different format) issued

by MUP (1974 and 1985). Then in 1991, Penguin Books chose it for inclusion in their

Australian War Classics series, with a Foreword by âWeary' Dunlop. It has thus been

in and out of print, but usually available ever since 1959.

It amazes and delights me that so plain and unembroidered a tale of one man's travels

sixty years ago still finds its readers. But when asked, as sometimes happens, âHow

do I feel about it all now?' it is hard to find an answer.

There is certainly âno memory for pain' in the ordinary

sense; the torn feet, the

ribs broken from falls, the intensifying bouts of depressing malaria â all that

vanished years ago. But several curious things still linger with perfect clarity.

There were for example, two separate days â only two â when I felt that I was on

the very brink of madness from loneliness and strain. A stern self-lecture on the

virtues of the stiff upper lip seemed to do the trick â perhaps

just

in time.

There was a day on which, at the end of a week of being hunted by the Japanese (said

now to be assisted by tracker dogs) I sought refuge by climbing a stupendous dry

cascade of huge boulders, as it ascended ever higher up a mountainside. At about

10,000 feet I sat down to rest a while, and from a sudden recollection of a school

geography lesson, realized that this chaotic wasteland of random-strewn rocks was

the moraine left behind in the retreat of an ancient glacier. Altitude and exhaustion

play hallucinatory tricks, but a great voice seemed to boom in my ear: âThis is the

end of the Earth! This is the end of the Earth! You've reached the end of the Earth!'

I remember my answer exactly. I said: âIf ever I get out of this, I'll never travel

anywhere again.' This was not in any sense intended as a vow, yet it was what happened.

Now seventy-seven, I have never been to England, Europe or America, and have never

wanted to go.

At times, every night for weeks at a stretch, when the Japanese were close, I lay

down to sleep with the lively expectation of being dead by dawn. Certainly this frightened

me, but I had learned by then that tranquility can be preserved even in the midst

of terror: mostly I slept as sweetly as if I had been in bed in my mother's house.

Wellâ¦all these are idle memories of a war long won â or perhaps lost. But most of

all, looking back, my main feeling is of gratitude. Dispatching an eighteen-year-old

on such a job as mine was heartless and irresponsible. And yet it was the best thing

that ever happened to me: I got the chance to discover what I could do, and I am

grateful.

P.R. October 2000

âAnd in the Military Service, there is a busy kind of Time-Wasting.'

ERASMUS OF ROTTERDAM

(1466â1536)

The Education of a Christian Prince

âTerrors shall make him afraid on every side, and shall drive him to his feet.'

The Book of Job

, 18.11

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK

is completely factual. The events it describes happened, and the people

mentioned in it lived â or still live. It treats its subject â war â on the smallest

possible scale. It does not aspire to chronicle the clash of armies; it does not

attempt to describe the engagements of so much as a platoon. It tells what happened

to one man â what he did, and how he felt about it.

However, it will be helpful to the reader to have some knowledge of the background

against which the story takes place; to supply that necessary glimpse of the wider

picture is the purpose of this short introduction.

New Guinea represented the most southerly extent of Japan's all-conquering Pacific

offensive of 1941â2. And it was in New Guinea â at Milne Bay â that the Australians

inflicted the first land defeat on Japan. The campaign in the world's largest island

therefore embraced both the nadir of our fortunes and the turning of the tide in

our favour. New Guinea was also the stern schoolroom in which we

learnt the tactics

and techniques â for example, jungle warfare â which led us finally to victory in

1945.

The events described in the following chapters deal chiefly with the period of our

unrelieved defeats, when the character of the war in New Guinea was most curious

and interesting.

The Japanese took Rabaul in January 1942 after heroic, but hopeless resistance, from

the Australian garrison. In March they occupied the important north-coast towns

of Lae and Salamaua. There was no resistance. What could a few dozen men of the New

Guinea Volunteer Rifles do against the Japanese who swarmed in thousands from their

landing-craft? In much the same way the Japs helped themselves at their leisure to

the greater part of the north coast. They made an assault on Port Moresby itself

which came very near to success.