Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine (24 page)

Read Fearless on Everest: The Quest for Sandy Irvine Online

Authors: Julie Summers

Tags: #Mountains, #Mount (China and Nepal), #Description and Travel, #Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Andrew, #Mountaineering, #Mountaineers, #Great Britain, #Ecosystems & Habitats, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Irvine, #Everest

The whole run from the top of the glacier to Goppenstein was supposed to take some seven hours. They had done it in three and a half. ‘Fritz said he’d never done it so fast before’ recalled Knebworth cheerfully, ‘and he was sweating like an old hog when he arrived. We could have done it twice as quick if we’d hurried on the glacier and been sober down the path.’ They changed and bathed in Spiez and caught the 9.33 back to England ‘with heavy hearts and a feeling that we shouldn’t do it again for a year….’

If Mürren had been seen as a foretaste of things to come then Sandy was flying even higher than he had been before he left Oxford. With that trip behind him and a little more experience under his belt he was looking forward more than ever to getting on with the ‘real show’.

On his return from Switzerland Sandy went back to Oxford for three days to make final preparations there before leaving for Birkenhead. There was still much work to be done on the oxygen apparatus and he was disappointed not to have had a reply from Siebe Gorman about his suggestions for design modifications. He had arranged to go up to 20,000 feet in an aeroplane to get a feeling for the altitude. This was organized for him by Evelyn who, during her time at Oxford, had joined the predecessor of the Flying Squadron and had earned her wings flying Avro 504s. As these planes don’t fly above 15,000 feet I have to suppose that it was not Evelyn who piloted Sandy’s plane but one of her contacts at the flying school.

Shrewsbury School had invited Sandy to lecture to the boys at the end of January on his Arctic trip. Odell sent him his paper on the mountains of Eastern Spitsbergen but Sandy was not confident about the prospect of speaking in public and confided in Odell that he was ‘just terrified’. Whatever he said at the lecture it went down well both with the boys and the masters. He presented the school with a copy of the 1922 Everest expedition book

The Assault on Mount Everest

which he signed and dedicated. After Sandy’s death many of the masters who wrote to Willie alluded to his talk. Baker, his old chemistry teacher, wrote: ‘When he last was here he more than ever endeared himself to us and won the admiration of all who listened to his lecture on his achievements in the far North. I felt as I listened to him that Shrewsbury had pride in so fine a son.’ The headmaster went even further: ‘There was a nobility and a selflessness in his whole bearing which deeply impressed us and with it all a reality of affection for each one of us which touched us unspeakably.’ Harry Rowe, then the head of Sandy’s old house, spoke for the boys in a letter that arrived the day Sandy sailed for India. He wished Sandy luck but cautioned: ‘remember to bring back those two feet off the top of Everest, so that even though we may not have any Cups in Hall, we can at least put the summit of Everest on it, with a House-Colour ribbon round it!! Cheerio! And keep away from Dusky Maidens, & their allurements!!!’. He finished the letter by illustrating the notice he had posted on the house board:

The following will represent Moores v. Everest in the Final of the Mountain Climbing Expedition: A. C. Irvine

Techniques today are utterly different from those of the pioneer period in the Himalaya. It is unhistorical to look at the expedition of 1924 through modern eyes without making allowances for these differences.

Herbert Carr,

The Irvine Diaries

Much was made in the press after the discovery of George Mallory’s body in 1999 of the woeful inadequacy of the clothing he was wearing: cotton and silk underwear, a flannel shirt, a long-sleeved pullover, a patterned woollen waistcoat (knitted for him by Ruth) and a windproof Shackelton jacket. On his legs he was wearing a pair of woollen knickerbockers and woollen puttees and on his feet hobnailed boots. Inadequate in terms of what is now worn on Everest certainly, but the fact remains that two men wearing similar clothing succeeded that year in gaining a height of more than 28,000 feet without using supplemental oxygen, a record that stood until 1978. And that is without knowing exactly how high Mallory and Sandy got with oxygen.

It is only too easy to stand in judgement from today’s perspective but it cannot be forgotten that both the Poles had been conquered by 1912 and the conditions met by the polar explorers were at least as inhospitable as those the climbers met on Everest. The fundamental difference between then and today, as I understand it, is in the materials that they were using for clothing and footwear. The design of the boots, for example, has altered relatively little but nowadays leather has been replaced by a lighter and warmer man-made material. When I spoke to Rebecca Stephens, the first British woman to climb Everest, we talked at some length about the clothing from the 1920s. She has strong opinions as she climbed in the Alps, for a children’s television programme, wearing hobnailed boots. She found them to be relatively comfortable and very reliable on slippery rock, where they had better grip in her view than the modern boot and crampon alternative which, although excellent on snow and ice, is less than perfect when it comes to rock and loose ground. The terrain above the North Col on Everest is rock rather than snow, so perhaps their ‘woefully inadequate’ footwear, which has been so universally derided, was not quite as bad as some people have made out.

They knew then that the best way to keep warm was to dress in layers and to wear silk or wool close to the skin. What they didn’t have was down, goretex and polar fleece but nor did Hillary and Tenzing when they made their ascent in 1953. I have talked to several high altitude mountaineers and they all agree on two things. First, the overwhelming advantages of today’s clothing is that it is breathable and light: wool, gabardine and tweed can be very heavy and restrict movement. Second, if anyone were caught out for a night on the high mountain in 1924 clothing they would have no chance of survival. Nowadays there is a chance that a climber can survive for a night or sometimes more. But that is only of use if they can then be rescued or get down the next day under their own power. Where Sandy and Mallory died they had no chance of being rescued.

The 1924 expedition benefited from the best research and the most advanced equipment available at the time. Not only had they had the experiences of the 1921 reconnaissance mission and the 1922 assault to draw upon, but they had also made great advances on the clothing used in the Antarctic by the Scott Polar expedition of 1911-12 and in oxygen technology for which the research had been carried out by the RAF. Several of the appliances, articles of clothing and of course the tents had been specially designed for the expedition. They firmly believed they were wearing and carrying the best of the best, which indeed they were for the time.

The Mount Everest Committee had to organize every last detail of getting the supplies shipped out to Calcutta on time and in good condition. It was comparable to a military operation and with General Bruce and Colonel Norton in charge it ran as smoothly as a well-organised campaign. The Committee issued a long list of necessary items annotated by Norton with his usual dry wit. Members were even advised to take their own saddles – not a piece of equipment much used by modern-day Everest climbers. The note reads, ‘Tibetan saddles are the acme of discomfort’ and goes on to give a name of a second-hand saddlery company in St Martin’s Lane where such equipment can be acquired. The list ran to four pages and the budget for acquiring the equipment was £50, or about £1500 in today’s money. The first items on the list were windproof clothing to be acquired from Messrs. Burberry, Haymarket (‘ask for Mr Pink’), the Shackelton range of windproof knickerbockers, smoks and gloves. Norton added a note: ‘a knickerbocker suit of this sort supplied to Major Norton was a great success last year’. The next item was Finch’s eiderdown quilted balloon cloth coat which, years ahead of its time, was laughed at by the 1922 expedition team and was dismissed by Sandy with a simple strike of the pencil.

General Bruce was a big fan of puttees and persuaded the committee to issue them to the expedition as standard. The photograph taken by Odell of Mallory and Sandy leaving Camp IV shows them quite clearly. A puttee comprises a long strip of cloth, in this case the finest cashmere wool, that is wound spirally around the leg from the ankle to the knee. Not only were they warm and comfortable but Bruce was convinced they offered support to the leg as well.

Messrs Fagg Bros. in Jermyn Street supplied a felt boot with leather sole, which was to be made large enough to accommodate three pairs of socks. As this new boot was an experiment they were also advised to purchase a pair of Alpine climbing boots which the committee recommended they had ‘nailed’. The leather sole of the boot has hobnails, but in addition to that, little metal plates about 1 centimetre long, are driven between the inner and outer soles to give extra grip. Some of the ‘nails’ are serrated. Norton goes into great detail about these nails, not least as some believed that the conductivity of the metal caused the foot to get prematurely cold. He sets out his case at great length, recommending a certain design and then recommending a felt sole to be added between the welt and the nailed sole but concluding, ‘Boots should be sparingly nailed for lightness – every ounce counts.’

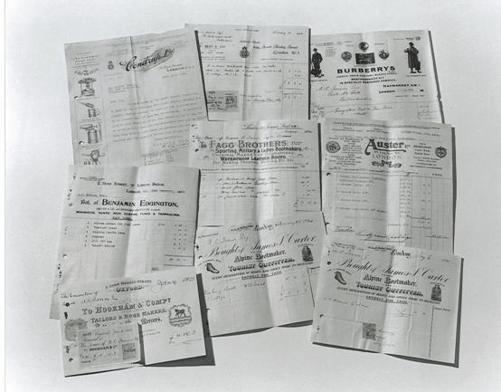

A selection of bills from Sandy’s collection showing equipment he purchased for the expedition

A selection of bills from Sandy’s collection showing equipment he purchased for the expedition

When I read the reference to camp equipment I really began to get a feeling for how extraordinarily tough these men were. ‘Camp bed is not strictly necessary; it is a comfort up to Phari and in the Kama valley in wet weather. A camp chair is a comfort in tent and for dining (the alternative being a ration box).’ I find it a little difficult to conceive of sitting on a ration box for five months and I was glad to see that Sandy bought himself a camp chair. ‘An X pattern bath and basin is sound; a bath between two is probably sufficient. A camp table is a luxury; a private folding candle a necessity’ the list went on.

Under ‘Miscellaneous’ they were advised to take out a dinner jacket, to be worn with a soft shirt as opposed to a stiff collar, a big umbrella, also available in Darjeeling at a competitive price, and one packet of Dr Parke Davis’s germicidal soap. Presumably not all to be used simultaneously.

The expedition supplied the tobacco duty free to the team members and asked them to let Norton know which was their preferred brand. Sandy, who seemed very much to enjoy his pipe and was frequently photographed with it, appears to have foregone smoking for this trip: he makes no reference to it in his diary and letters, nor are there any photographs of him smoking. Finch had argued in 1922 that he and Geoffrey Bruce had derived benefits from smoking at altitude.

Sandy’s final bill for his equipment, minus the tool kit, primus burners and spare parts for the oxygen kit which he paid out of his own pocket, was about £75 (or £2250 today). He was finally reimbursed for his equipment plus the additional kit he had ordered on behalf of the expedition to the tune of £86 1s 1d in May 1924 which, he told Willie Irvine cheerfully, should help to reduce his overdraft.

With a sigh of relief Sandy returned to Birkenhead to spend the final month before leaving England with his family, although he made three further trips to London at Unna’s request to finalize details about the oxygen equipment and stoves. He had collected from Oxford the oxygen apparatus and set to work on it in his workshop at Park Road South. Still having heard nothing from Siebe Gorman he pressed on with his modifications, the realization dawning on him that he was in all probability going to have to effect some fairly major alterations as soon as he met up with the apparatus in its final form in India. He was also occupied with putting together the tool kit and ensuring that the primus stoves and burners that Unna had asked him to take responsibility for were up to standard. Unna had a great deal of faith in Sandy’s mechanical capabilities and had given him a free hand in ordering the tools he thought might be required. Sandy sent his list to Spencer at the Mount Everest Committee saying that he regarded it as adequate for looking after the oxygen apparatus, primus burners and the ladder bridge. He added: ‘they all pack in quite a small box and none are very heavy; the vice is not a large affair at all and would clamp onto a box or table or any old thing like that.’ He had also recommended a pair of Bernard Revolving Pliers for punching holes in leather and a variety of stocks and dies which, he added quickly, would not depreciate in value and could be brought home intact.

Although Odell was appointed oxygen officer Unna addressed all his communications on that subject and on all other matters to do with the stoves to Sandy, asking him to ensure Odell received copies of the letters. This was in part a shift in Unna’s thinking but it was also necessitated by the fact that Odell was on his way to Persia on company business prior to his arrival in India.

Hinks had arranged for Sandy to travel from Liverpool in the company of George Mallory, Benthley Beetham and John Hazard at the end of February. Other expedition members would be travelling from different parts of the Indian subcontinent and of course Odell from Persia and they would all meet up in Darjeeling at the end of March.