Feminism (14 page)

Authors: Margaret Walters

Tags: #Social Science, #Feminism & Feminist Theory, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #History, #Social History, #Political Science, #Human Rights

her something like three years to realize that something was missing. Her second marriage, to Humphrey Roe, never proved quite as rapturous as she had hoped, though he gave her valuable support when she later opened a birth control clinic. But Stopes at least found effective ways of moving through her own ignorance to help other women who might be almost as uninformed as her younger self. She went on to write

Married Love

(1916), which sold 2,000 copies in a fortnight, and by the end of the year had reached 92

six editions. It was followed by

Wise Parenthood

(1918) and

Radiant

Motherhood

(1920). Her style was – well, flowery: the half swooning sense of flux which overtakes the spirit in that eternal moment at the apex of rapture sweeps into its flaming tides the whole essence of the man and woman.

This (not altogether convincing) bliss was in stark contrast to another, darker but equally fantastic, vision of the thriftless who breed so rapidly [and] tend by that very fact to bring forth children who are weakened and handicapped by physical as well as mental warping and weakness, and at the same time to demand their support from the sound and thrifty.

Early 20th-centur

But Marie Stopes proved herself a loyal friend to Margaret Sanger.

When Sanger returned to America and again faced prosecution, Stopes came to her support, not only organizing a petition on her behalf, but writing, with characteristic drama, to the President of

y feminism

the United States:

Have you, Sir, visualized what it means to be a woman whose every fibre, whose every muscle and blood-capillary is subtly poisoned by the secret, ever growing horror, more penetrating, more long-drawn than any nightmare, of an unwanted embryo developing beneath her heart?

Marie Stopes’s books – their practical side, at least, clearly answering an urgent need – continued to sell very well indeed.

When she insisted that ‘the normal man’s sexual needs’ are not

‘stronger than the normal woman’s’, she obviously touched a chord in many other women. She and Reginald Gates went on to set up a birth control clinic in Holloway, North London, where poor women were offered free contraceptive advice. The clinic’s brochure claimed that they were offering health and hygiene to the internally damaged ‘slave mothers’ who yearly produced their ‘puny infants’, 93

but were ‘callously left in coercive ignorance by the middle classes and the medical profession’. But Marie Stopes also managed to antagonize many of the people who shared her interests and who might have worked effectively with her. In 1928, one possible colleague complained that she was suffering from ‘paranoia and megalomania’.

In 1936 a group of women tackled an even more controversial issue, when they founded the Abortion Law Reform Association.

Something like 500 women a year were dying from abortions, they argued; and that was quite unnecessary. One of their campaigners, the Canadian-born Stella Browne, had the courage to admit publicly that ‘if abortion was necessarily fatal or injurious, I should not be here before you’. The issue remained controversial into (and beyond) the 1950s, when several women’s organizations began to press for the legalization of abortion. In 1956, a newspaper survey found that, out of 200 people questioned, 51.9% favoured abortion on request, and 23.4% for health reasons. But abortion remained a

minism

major, and often problematic, issue long after the revival of

Fe

feminism in the 1970s.

Virginia Woolf has been dismissed as irrelevant by some contemporary feminists; Sheila Rowbotham, for example, remarks that her demand, in

A Room of One’s Own

, for £500 a year and space to oneself was simply aimed at a minority of the educated middle class. That is true; but she is read still, and by women (and men) who would never so much as glance at most feminist writing. Woolf was certainly ambivalent about the term

‘feminism’; she admitted that she was anxious, when the book was first published, that she might be ‘attacked for a feminist’. In

Three Guineas

– a later and much darker book, written in the shadow of approaching war and the growth of fascism – Woolf directly attacks the word ‘feminism’; it is ‘an old word, a vicious and corrupt word that has done much harm in its day and is now obsolete’. Her plea to ‘the daughters of educated men’ – rather than simply to educated women – now sounds rather clumsy, 94

and in the 1930s must have already been rather dated. (By educated men, she explains that she means those who had been at Oxford or Cambridge.) But she refers effectively and scathingly to ‘Arthur’s Education Fund’ that for decades, even centuries, has allowed boys, but not their sisters, to be adequately taught; and she remarks sardonically that, until 1919, marriage has been ‘the one great profession open to women’. Moreover, she adds, they were actually unfitted even for that by their lack of education.

In

A Room of One’s Own

, Virginia Woolf defends Rebecca West, who had just been attacked by a man who labelled her an ‘arrant feminist! She says that men are snobs!’ The suffrage campaign, Woolf fears, ‘must have roused in men an extraordinary desire for self-assertion’. After all, she remarks, ‘women have served all these

Early 20th-centur

centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size’. In fact, she insists, most women have little idea how much men actually hate them. ‘The history of men’s opposition to women’s

y feminism

emancipation’, she remarks dryly, ‘is more interesting perhaps than the story of that emancipation itself. An amusing book might be made of it.’ But the writer, she adds, ‘would need thick gloves on her hands, and bars to protect her of solid gold’. And, after all, what seems amusing now ‘had to be taken in desperate earnest once . . .

Among your grandmothers and great-grandmothers there were many that wept their eyes out.’

Glancing at a modern novel by the fictional writer ‘Mary Carmichael’, Woolf comes upon the words ‘Chloe liked Olivia’, ‘And then it struck me how immense a change was there. Chloe liked Olivia perhaps for the first time in literature.’ That is to say, women in fiction up until that time had almost always been seen in relation to men. Reading on, Woolf learns that these two women share a laboratory, ‘which of itself will make their friendship more varied and lasting because it will be less personal’. And she exclaims that Mary Carmichael may be lighting a torch where nobody has yet 95

been, exploring a place where ‘women are alone, unlit by the capricious and coloured light of the other sex’.

In perhaps the most memorable pages of

A Room of One’s Own

, Virginia Woolf sums up her argument about how women’s talents have been – and often still are – frustrated and wasted. She contemplates a number of greatly talented women from the past, from the Duchess of Newcastle to George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë – who were deprived of ‘experience and intercourse and travel’ and so never wrote quite as powerfully and generously as they might have done. Woolf invents the hauntingly effective figure of Shakespeare’s sister, as gifted as her brother, but inevitably disappointed, mocked, and exploited by men. Like her brother, Judith arrived hopefully at the London theatres, but soon ‘found herself with child . . . and so – who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body? – killed herself one winter’s night and lies buried at some cross-roads where the omnibuses now stop outside the Elephant

minism

and Castle.’ But ‘she lives in you and in me, and in many other

Fe

women who are not here tonight, for they are washing up the dishes and putting the children to bed’.

96

What is sometimes termed ‘second-wave’ feminism emerged, after the Second World War, in several countries. In 1947, a Commission on the Status of Women was established by the United Nations, and two years later it issued a Declaration of Human Rights, which both acknowledged that men and women had ‘equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution’, as well as women’s entitlement to ‘special care and assistance’ in their role as mothers. Between 1975 and 1985, the UN called three international conferences on women’s issues, in Mexico City, Copenhagen, and Nairobi, where it was acknowledged that feminism constitutes the political expression of the concerns and interests of women from different regions, classes, nationalities, and ethnic backgrounds . . . There is and must be a diversity of feminisms, responsive to the different needs and concerns of different women, and defined by them for themselves.

African women offered a salutary reminder that women are also members of classes and countries that dominate others . . . Contrary to the best intentions of ‘sisterhood’, not all women share identical interests.

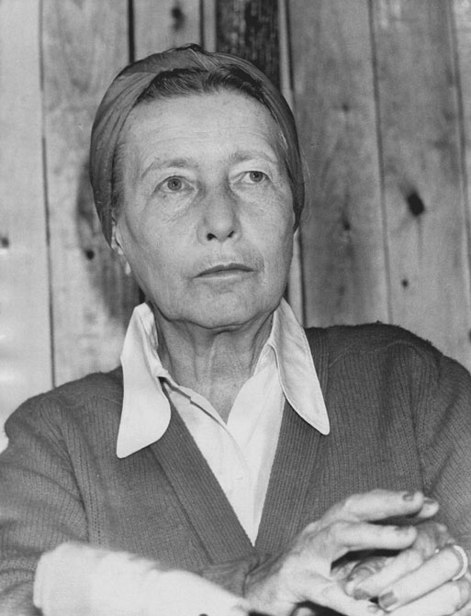

A remarkable variety of Western women picked up their pens. One 97

of the most influential was, and remains, the French writer Simone de Beauvoir. Her writings – including four volumes of autobiography and several novels – add up to a remarkable exploration of one woman’s experience; women from many other countries responded, saying that Beauvoir’s

The Second Sex

(1949) had helped them to see their personal frustrations in terms of the general condition of women. All through history, Beauvoir argues, woman has been denied full humanity, denied the human right to create, to invent, to go beyond mere living to find a meaning for life in projects of ever-widening scope. Man ‘remodels the face of the earth, he creates new instruments, he invents, he shapes the future’; woman, on the other hand, is always and archetypally Other. She is seen by and for men, always the object and never the subject.

Through chapters that range over the girl child, the wife, the mother, the prostitute, the narcissist, the lesbian, and the woman in love, Beauvoir explores different aspects of her central argument: it

minism

is

male

activity that in creating values has made of existence itself a

Fe

value; this activity has prevailed over the confused forces of life; ‘it has subdued Nature and Woman’. Woman, she argues, has come to stand for Nature, Mystery, the non-human; what she

represents

is more important than what she

is

, what she herself experiences.

But ‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’, Beauvoir insists; and she can change her condition. Most women, mistakenly, look for salvation in love. But Beauvoir’s own alternative is perhaps too simple: she conjures up an image of the ‘the independent woman’ who

. . . wants to be active, a taker, and refuses the passivity man means to impose on her. The modern woman accepts masculine values; she prides herself on thinking, taking action, working, creating on the same terms as man.

That is not really an attractive image of our possible future. But, she 98

adds rightly, too many women cling to the privileges of femininity; while too many men are comfortable with the limitations it imposes on women. Today, women are torn between the past and a possible, but difficult and as yet unexplored, future.

Beauvoir was always opposed to any feminism that championed women’s special virtues or values, firmly rejecting any idealization of specifically ‘feminine’ traits. To support that kind of feminism, she argued, would imply agreement with

a myth invented by men to confine women to their oppressed state.

For women it is not a question of asserting themselves as women, but of becoming full-scale human beings.

Secon

d-w

But though Beauvoir was and remained critical of some forms of

av

traditional feminism, she was impressed by the emerging

e feminism: th

Mouvement de Libération des Femmes (MLF), admitting in a 1972

interview that she recognized that

e lat

it is necessary, before the socialism we dream of arrives, to struggle

e 20th centur

for the actual position of women . . . Even in socialist countries, this equality has not been obtained. Women must therefore take their destiny into their own hands.

y

Beauvoir was one of the women who signed a 1971 manifesto published in the

Nouvel Observateur

, drawn up by an MLF group, who were campaigning to legalize abortion; 343 women signed it, proclaiming ‘I have had an abortion and I demand this right for all women.’ However, she always insisted (not wholly convincingly) that she herself had no personal experience of women’s ‘wrongs’, that she had escaped the oppression that she analyses so brilliantly in

The Second Sex

.

Far from suffering from my femininity, I have, on the contrary, from the age of twenty on, accumulated the advantages of both sexes . . .

those around me treated me both as a writer, their peer in the 99

masculine world, and as a woman . . . I was encouraged to write

The

Second Sex

precisely because of this privileged position. It allowed me to express myself in all serenity.