Fields of Home (15 page)

Authors: Marita Conlon-Mckenna

She grabbed her battered hold-all and started to pull stockings and underwear from the makeshift line she and Kitty had strung from the beams. She added her two good blouses and fine wool skirt and the lavender-coloured floral print dress she had saved for and bought last year. Her two nightdresses – one dirty, one clean – her flannel, cologne and a bar of scented soap. From the hook behind the door she took her warm winter coat, and her stout black brogues from under the bed. She retrieved her bank book, along with some letters from under the mattress, a few books, and finally her family bible, where Nano had written the names on her family tree. Soon there would be another name added to it when Peggy O’Driscoll married James Connolly. She ran her finger excitedly along the page of writing.

She stopped and stared. The room seemed suddenly empty, the two brass beds deserted. Fingering the horse-hair bracelet that Michael had made for her when she was leaving home for America, Peggy remembered the good times here with Kitty, but now she knew there would be good times ahead too. With a sigh, she pulled the door closed after her, frightened that James would be gone or that she had imagined it all.

He was not. He was sitting in the kitchen with the cook and the housekeeper who were chatting away to him like old friends.

Perhaps Miss Whitman would insist on her working her proper notice or object to her leaving like this? Peggy felt scared as she stood in the kitchen and lowered her bag to the floor.

‘Miss Whitman, I’m sorry about my notice, but I … I have to go … now,’ she said firmly, her eyes meeting those of her future husband.

Miss Whitman did not seem too put out. ‘There’s a lot to be said for the rules of the heart! You don’t want to end up like me, Peggy lass.’

‘Will you explain to Mrs Rowan about me leaving?’ Peggy said. ‘She’s been so kind to me over the years and I hate letting her down.’

Mrs O’Connor was blowing her nose loudly. ‘Oh Peggy, dear! I’ll truly miss you. What will I do without your big brown eyes listening to my stories and cheering me up?’

Peggy hugged the motherly cook. ‘You’ll tell Kitty what happened, won’t you? And send me her address when I’m settled? I’ll write to you all. I promise.’

‘Of course!’ Mrs O’Connor agreed. ‘Now, I’ve told your young man that Father Vincent does the early mass in Saint Patrick’s – he married my daughter, you know. He’ll look after you.’

‘Oh thank you, Mrs O’Connor,’ beamed Peggy. ‘Sarah can be my bridesmaid –’

‘Peggy, what will I do about your wages?’ broke in Miss Whitman. ‘There’s at least a month due and Mr Rowan had intended a special bonus for all the help with the wedding.’

Peggy considered. She had her bank book. There would be money there to purchase lumber and horse-feed, and curtains and blankets – all the things herself and James might need. Now that she would have a home of her own to build, Eily would miss the small twice-a-year gifts she sent her.

‘I’m not sure where I’ll be next month or the month after,’ she said. ‘I’ll tell you what, Miss Whitman, would you ever be so kind as to send it to my sister, Eily, back home in Ireland? Here, I’ll scribble the address for you. Tell her it’s a present from me.’

Hugging them both and laughing with pleasure, Peggy O’Driscoll said her last farewells to Rushton. Then she and James sat arm-in-arm in the cart as they drove away from the house.

THE GINGER-HAIRED MAN

with the bristly bit of a moustache came back, just as he had promised.

Every night for the last week, Eily and John had emptied out the small earthenware jar they kept hidden under the bed and counted out their money. They had got a fine price for Muck and the hen-money added some more; then there was all they’d made on two visits to the market. Still, no matter how they added it up, they were short the amount due. Mary-Brigid wished for a miracle that would change the copper coins into silver or gold.

‘Come inside, Mr Brennan,’ said John. ‘We have the money for you.’

They all watched anxiously as the man counted out the money into the palm of his hand.

‘Mr Powers, there seems to be some sort of

misunderstanding. This amount falls short of the terms agreed.’

John’s wide hands gripped the table. ‘There’s no mistake, Mr Brennan. That’s all there is. I’ve nothing left to sell. My rent is double what it was this time last year. It’s all I’m able to pay. You’ll have to tell that to Mr Ormonde!’

Mr Brennan seemed embarrassed. He looked around the cottage, taking in the young husband and wife with their two small children, and the old lady in the corner who glared fiercely at him. He hated this job of rent-collecting for Hussey.

‘I’ll talk to them, Mr Powers. Are ye sure you’ve nothing else to give me?’ he prodded.

‘No!’ said John firmly. ‘There’s only the food on the children’s plates and the clothes on their backs. Tell Dennis Ormonde that I have worked as hard as any man can work – and that’s all I have!’

Mary-Brigid watched as Mr Brennan scooped their money into a leather bag. ‘I’ll talk to Mr Hussey on your behalf,’ promised the man, now anxious to leave. They all watched as he hoisted himself onto the saddle of his sturdy grey mare and rode away.

‘Now we wait!’ said John seriously.

THEY WAITED AND WAITED

– and they made their plans. Mary-Brigid helped her father to fill a huge sack with potatoes, which he and Michael dragged into the cottage. Every spare pot and pail and jar was filled with water from the well and put to stand in the coolest part of the kitchen, and no clothes were left on the washing line. John’s work-tools were brought in from the small outhouse, and now his spade, pitchfork, scythe and hoe stood against the kitchen wall. Maisie, too, was brought in, and she spent her time clucking angrily at Scrap, who was none too pleased with the visitor. Nano and Eily checked the flour and oatmeal barrels, and Michael and John dragged the huge kitchen dresser, which Mary-Brigid’s grandfather had made, over beside the door.

‘Mary-Brigid, you are to keep an eye on your little brother. You must not go more than a few yards from the house. Do you understand me?’ ordered her father.

‘Aye,’ she said, fearful of what was going on.

That night she slept fitfully, and in the morning found that Michael’s settle bed near the fire had not been slept on.

‘Michael’s gone!’ She ran to her parents with the news.

‘This isn’t his fight,’ said Nano. ‘And he has things to see to …’

Mary-Brigid looked out the cottage door. ‘The horses are gone too!’ she announced.

At midday Mary-Brigid’s heart leapt when she heard the sound of horses’ hooves in the laneway. She stared down the boreen; it was Mr Brennan and four other men.

‘Inside, Mary-Brigid,’ ordered John sharply. ‘Stand back from the window.’

He bent down and put his shoulder against the dresser. Then he and Nano and Eily strained to shove the heavy weight against the door.

After a few minutes a voice called out: ‘Mr Powers, it’s me, Tom Brennan. I’m afraid the amount you paid is unacceptable. Your landlord is insisting on the correct amount.’

‘I told you, I don’t have it!’ shouted John.

Another voice spoke. ‘By the order of the landlord

Dennis Ormonde, you, John Powers, and your dependants are asked to quit this holding.’

‘’Tis Hussey!’ said John.

William Hussey sat astride his large, chestnut horse. One side of his severe-looking face seemed almost crooked, the skin puckered and scarred. His left arm hung uselessly at his side.

‘I’ll not quit!’ yelled John. ‘Tell Ormonde I’ll give up the low field if that will reduce the rent.’

Low voices spoke outside, as if arguing. Then Mr Hussey rode closer to the door. ‘This land will not be divided up,’ he announced. ‘There’s no arguing. You either pay the full rate for this holding or you give it up. Mr Ormonde is a very busy man. He leaves the running of the estate to me.’

‘You just want this farm for yourself, Hussey! You’ll not get it!’ shouted John.

‘How dare you!’ The landlord’s agent cursed. ‘You’ve not heard the end of this! Not by a long chalk.’

Two men were left guarding the cottage while the others rode off. John hoped that Mr Brennan was honest enough to tell the landlord of his offer.

Night-time fell and the family hardly slept. Eily sat in a chair by the small window, keeping watch lest Hussey and his men came back.

In the morning the cawing of the rooks from the nearby woods woke them. Bleary-eyed, Mary-Brigid

had a sip of milk and a chunk of bread. Her father looked exhausted, but took over the watch. Eily dressed and washed Jodie and tried to amuse him. Nano finally roused herself, her old bones weary from it all.

William Hussey and his men returned, and they seemed to be pulling something. It was like a tree trunk, and they came to a halt with it just outside the door.

‘John Powers! Do you agree to pay the rent set by your landlord Dennis Ormonde?’ Mr Hussey said clearly.

‘I have given you almost double my previous rent,’ answered John in desperation. ‘I haven’t one brass farthing more. I have even offered to give up one of my fields to make up the shortfall.’

‘You have refused to pay the full rent!’ jeered Mr Hussey.

‘I have been a good tenant, just like my father and grandfather before me. I have no fight with Mr Ormonde. He knows that I’ve paid more than a fair rent,’ shouted John.

Mr Hussey turned his horse around. ‘We give you an hour to pack up your belongings and leave this dwelling,’ he declared.

Inside the small cottage they all stood bewildered and shocked, not knowing what to do. Jodie began to

cry and clung to his father, who hoisted him up in his arms. Nano began to move around, folding things, putting them in small bundles.

‘What are you doing, Nano?’ said Eily.

‘I’m beginning to pack up,’ said Nano quietly, trying to hide the despair in her voice.

‘We are not packing up, Nano!’ said John firmly. ‘Sit down. All of ye sit down!’

From his face and manner, Nano knew that this was one time to respect the young man’s wishes.

Mary-Brigid felt so nervous that she could hear her own heart beating in her chest. Eily stood, looking helpless and as pale as a ghost. They all sat waiting.

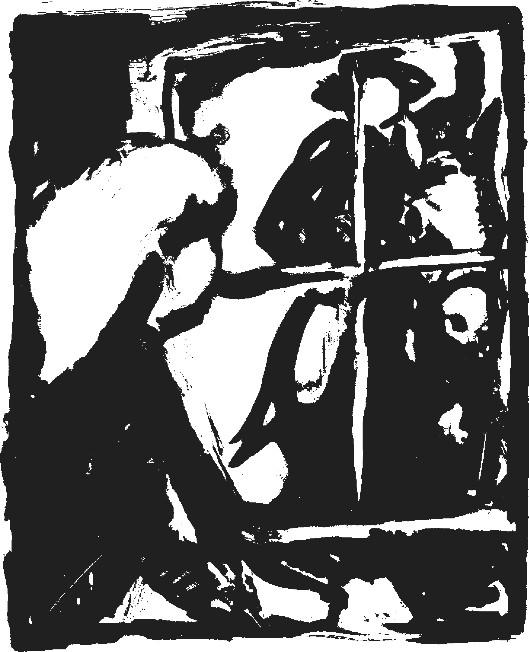

After an hour one of the men took a huge pitchfork and began to pull the straw from the thatched roof. The others moved the tree-trunk closer to the house. Mary-Brigid closed her eyes, waiting for the thud as it hit against their wooden door.

‘Now!’ called William Hussey.

The men gave a huge push and the small cottage seemed to shudder as the ramming tree-trunk battered against the door, but the heavy old oak dresser took the brunt of the impact.

‘Again!’ ordered Mr Hussey.

The family braced themselves for another thud, and within the space of a few minutes their home was hit again, and again. The door split and it was obvious that

the dresser could not hold for much longer. There was a gaping hole in the roof too, through which they could see the sky. Then someone blocked the chimney in an effort to smoke them out. Stinging tears ran down their faces, and the smoke made them cough and choke.

Mary-Brigid guessed that they would have to leave soon. Poor Jodie was choking so badly he could scarcely get his breath. Barely moving, Eily held the child tightly to her, standing as if she had been turned into stone.

‘Mr Hussey! Mr Hussey!’

They all heard the shouts. It was Michael’s voice. Michael had come back.

‘Stop that! Stop those men!’ he yelled, as he ran towards the cottage. ‘Leave them be!’

William Hussey turned to face him. ‘Who the hell are you? What business of this is yours?’

‘Eily is my sister and this is her home.’

‘Her home, indeed!’ jeered the land-agent.

‘Mr Hussey! What do you think is the value of this holding and the cottage? How much would it cost to buy?’ questioned Michael, standing with his hands in his waistcoat pocket.