Finding the Dragon Lady (22 page)

Read Finding the Dragon Lady Online

Authors: Monique Brinson Demery

F

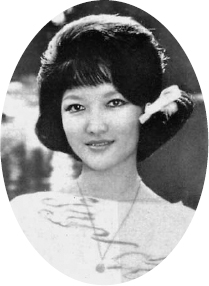

IGURE 3

. Portrait of Tran Thi Le Chi, Madame Nhu's sister

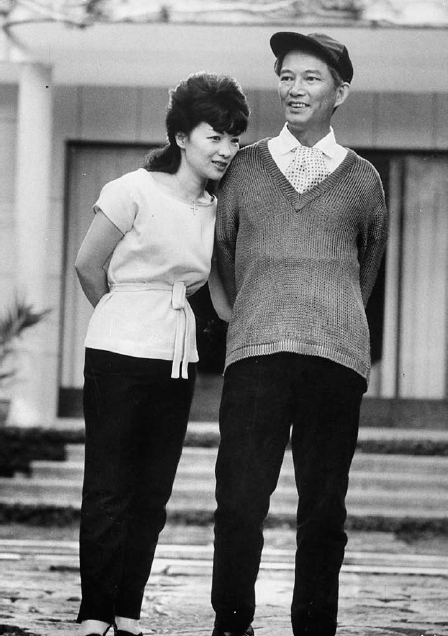

F

IGURE 4

. The South Vietnamese presidential family

F

IGURE 5

. Ngo Dinh Nhu and wife, Tran Thi Le Xuan

F

IGURE 6

. Madame Nhu playing with two-year-old daughter Le Quyen

F

IGURE 7

. Portrait of daughter Le Thuy circa 1963

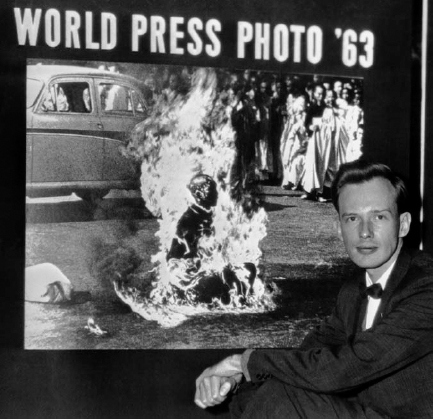

F

IGURE 8

. Malcolm Browne, Saigon correspondent, in front of his photo

F

IGURE 10

. Madame Nhu talking to the press at the airport as she is leaving Vietnam in 1963

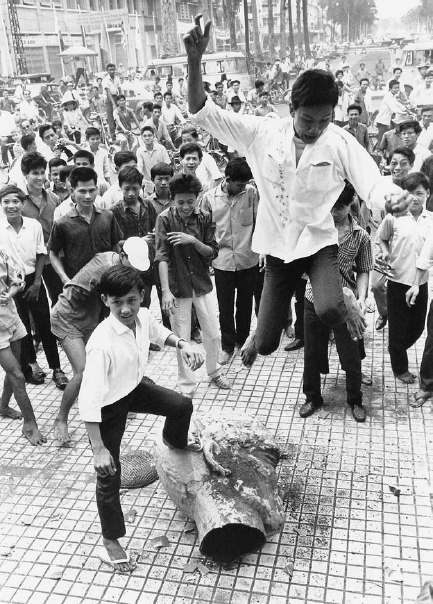

F

IGURE 11

. Barefooted Vietnamese youth about to come down on the head of the Trung sister statue

“D

AVID HALBERSTAM

died yesterday,” I mentioned carefully to Madame Nhu in April 2007. “It was a car crash.” I wasn't sure how closely she kept watch on current events. I was even less sure how she might react to hearing the name of the

New York Times

reporter and prolific author, whom she had known in Saigon all those years ago.

His obituary had run in the morning paper:

Tall, square-jawed and graced with an imposing voice so deep that it seemed to begin at his ankles, Mr. Halberstam came fully into his own as a journalist in the early 1960s covering the nascent American war in South Vietnam for the

New York Times

.

His reporting, along with that of several colleagues, left little doubt that a corrupt South Vietnamese government supported by the United States was no match for Communist guerrillas and their North Vietnamese allies.

1

“Mmmm,

The Best and the Brightest,

” she said, surprising me by immediately calling up the name of his 1972 book. “No, I did not know he had died. Too bad.”

She didn't sound very sad, but that wasn't surprising. From what I knew of Halberstam's reporting, he hadn't liked Madame Nhu, and the feeling had been mutual. He had called her “proud and vain” and accused her of “delving into men's politics with sharp and ill-concealed arrogance.” In his 1964 book

Making of a Quagmire,

Halberstam had said of Madame Nhu, “To me, she always resembled an Ian Fleming character come to life: the antigoddess, the beautiful but diabolic sex-dictatress who masterminds some secret apparatus that James Bond is out to destroy.”

2

He had written so critically about Madame Nhu's thirst for political power that she was said to have told someone in 1963, “Halberstam should be barbecued, and I would be glad to supply the fluid and the match.”

Maybe her feelings had mellowed over forty-four years, or maybe her memory had softened. But Madame Nhu's response to David Halberstam's untimely death forty-four years later shocked me with how fondly she recalled him. “He was intelligent, one of the rare ones who told the truth.”

Indeed, he had, both in

The Best and the Brightest,

which Madame Nhu had mentioned, and in the astute, on-the-ground reporting that won him a 1964 Pulitzer Prize. Halberstam's truths had made the US government uncomfortable and the military brass mad. He had been one of the first to point out that the war in Vietnam was not going well. He showed how, time and time again, the United States was bungling its mission in Southeast Asia. The academic and intellectual “whiz kids” in the Kennedy administration had arrogantly imposed policies that defied common sense. To Madame Nhu, it must have been at least a little vindicating to see the men who brought her family down tarnished by Halberstam's reporting.

But Halberstam had also loudly, and repeatedly, blamed the Ngo family for the American failure in Vietnam. His reporting was read very carefully in Washington. President Kennedy himself asked the CIA to study every story the young journalist wrote, and each of those CIA reports generated pages upon single-spaced pages of analysis. The

CIA concluded that the young journalist was more accurately informed about the facts on the ground in South Vietnam than most of the military “advisors.” He was right when he said that the Reds were making gains and right again in stating that the Communist guerrillas were well armed and “had the run of the delta.”

3

The CIA came to another important conclusion about Halberstam's reporting. His “invariably pessimistic” stories were contributing directly to a political crisis in South Vietnam. The CIA was holding David Halberstam responsible for the Ngo regime's crack-up. His reporting, they said, was contributing to its downfall. Had Madame Nhu ever known that little detail?

4

Halberstam and the other young men of the press corps in Saigon believed in the American mission in South Vietnam. They supported the domino theory so wholeheartedly that when they saw their government's policies being dragged down by Madame Nhu and her family, the pressmen seemed to take it upon themselves as good Americans to alter the situation in South Vietnam, as well as report on it. Their goal was nothing less than regime change.

They blamed the Ngos for nearly everything that was going wrong with the American-supported effort in South Vietnam. Not until after Diem and Nhu were gone did Halberstam himself conclude that for all his reporting on the faults of the Ngo regime, he had simply failed to be pessimistic enough. The problem wasn't just the arrogance of the aristocratic Diem, the obtuse intellectualism of Nhu, or the self-serving machinations of Madame Nhu. American chances for success in Vietnam had bogged down in a much more layered quagmire. But by then, it was too late.

5