Finding Zero (15 page)

Authors: Amir D. Aczel

20

When I came back to my hotel and turned on my computer, there was a much-anticipated message from Rotanak Yang (Andy Brouwer's friend). He told me that his father, who spoke no English, was the director of an institution called Angkor Conservation, where many Cambodian inscriptions, statuary, and other artifacts have been taken over the decades to protect and conserve them. K-127 might have been placed there. But Angkor Conservation had been looted in 1990 by the Khmer Rouge in the last recrudescence of their violence in Cambodia, and many of the pieces kept there had been destroyed or plundered. So it was unclear whether K-127 would still be there, if indeed it had ever been brought to this repository. And then he wrote, “But neither I nor my father can help you any further. In order for us to give you any more information, you need to contact the Cambodian Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts to obtain permission to receive our information.”

I closed my PC and sighed. Here I was, in Bangkok, waiting to go to Cambodia to look for the missing inscription, and now I needed to deal with a bureaucracy I didn't know or understand.

I thought about this new hurdle and sent a message back to Rotanak: “Would you please give me some idea as to where I should start this request? Do you know anyone at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts who I could contact?” I sent the message and went into town to visit Buddhist temples for inspiration.

Next to my hotel was one of the stops for the boats that ferry tourists and Thais up and down the Chao Phraya. I caught one of these packed boats going north and disembarked close to the Royal Palace. The palace was closedâas it was a holiday, the king's birthdayâand an armed guard chased me away when I tried to walk in through one of its gates. I crossed the street and within a block found the largest of the temple complexes in Bangkok, Wat Pho. This was the home of the famous golden reclining Buddha. I admired the 150-foot-long gold statue of the Buddha lying on his side, supporting his head with his hand. A sign inside the temple read, “Beware Non-Thai Pickpocket Gangs.” I instinctively touched my pocketâmy wallet was still there.

Outside, as I crossed the crowded street heading in the direction of the boat landing, a middle-aged man rushed toward me. He opened a color-picture brochure displaying photos of a naked woman. “Young girl,” he said, “young girl.” I literally pushed him away. This was the scourge of Southeast Asia. Ever since the Vietnam War, when the US military would bring its war-tired soldiers for rest and recreation in Bangkok, the people here found a lucrative trade in selling their women and girls to Westerners. But the improving economy has made the phenomenon less prevalent in recent years.

A few months earlier, at an international conference in Mexico where I had been invited to speak, I met Nicholas Kristof of the

New York Times.

When I told him that I was headed to Cambodia, he said that he had just returned from there. “When I was there, I bought from a brothel two Cambodian girls who had been forced into prostitution, and set them free and sent them into a program that would train them to live on their own,” he said. I was glad the world had people like him. He probably could have also bought the freedom of the young girl this pimp was peddling.

When I returned to the Shangri-La, there was an answer from Rotanak. “Try to contact H. E. Hab Touch,” he wrote. “I don't have a phone number or e-mail address, but maybe you can find it.” I didn't know what

H. E.

stood for, but I spent some time on the computer looking for Hab Touch. I recognized the name as that of one of the former directors of the Cambodian National Museum in Phnom Penh, which was a good sign. This man must know much about antiquities, I felt, and I hoped he would support my quest. I located his address and wrote him an e-mail message requesting his help in my search. But for a while there was no response.

After a few days, to my delight, Hab Touch answered my e-mail. He told me he and his people would look into it and try to find more information about the inscription's whereabouts. Mr. Hab (in Cambodia the surname comes first) then indeed spent a significant amount of time trying to help me find the inscription. He finally determined that on November 22, 1969, the artifact was sent to the place called Angkor Conservation (where Rotanak's

father worked) in Siem Reap, home of Angkor Wat and a thousand other smaller temples in the jungles and fields of western Cambodia. What happened to it afterward, no one knew. He suggested that I also contact the director of the local museum. It turned out that Chamroeun Chhan, whom my friend the art dealer in Bangkok had suggested I contact, was the director of that local museum in Siem Reap, and I was glad that two leads now pointed me to him. I would try to contact him later, but my greatest need now was to obtain information about K-127 from Angkor Conservation.

I therefore returned to Rotanak, but he insisted that I get formal permission to be given any more information on artifacts at Angkor Conservation. So again I wrote to Hab Touch, and in a few days the desired permission arrived. I was cleared to travel to Siem Reap to visit Angkor Conservation to look for the lost artifact. I could not believe my search was about to begin in earnest, and with a specific destination. I took note of what I now knew: K-127 was discovered in 1891 at Sambor on Mekong. By 1931, George CÅdès had translated it and realized that it contained the oldest extant zero and published his finding. The stele was taken to the national museum in Phnom Penh. In November 1969, it was moved to Angkor Conservation in Siem Reap. In 1990, a thousand artifacts from Angkor Conservation were destroyed or stolen by the Khmer Rouge. Now I had official permission to search for it at its last-known home. I packed carefully, planning for what could be a difficult search for something that might or might not be found. This quest could take a long time.

21

I was now headed to Siem Reap to see if K-127 still existed and could be located. Most important in this search, Hab Touch had told me on the phone that he would get me in touch with his people at Angkor Conservation, to see if they could locate this elusive artifact.

With these hopeful signs, I took a long taxi ride to the Don Meuang airport, the secondary Bangkok airport, and boarded an Air Asia flight to Siem Reap. Air Asia provided a comfortable flight in a two-engine turboprop plane, which can use far smaller runways than jets do. It took off after a couple of minutes on the runway, but the airline provided no food or drinkâyou had to pay even for a glass of water. On arrival, I went through the lengthy visa application process, had my picture taken, paid the fee (I knew they only accepted US dollars and I was prepared), and after an hour of immigration bureaucracy I emerged to find a cab to take me to my hotel.

The Angkor Miracle Resort Hotel, which caters mostly to Chinese visitors, turned out to be comfortable and surprisingly quiet given the number of tour buses that arrive each day. It was

Januaryâhigh season hereâand tourists mobbed the city. When I asked for a taxi, I got the only driver in town who knew absolutely no English or French: not

hello,

not

yes

or

no.

The reason for this was that he was not really a cab driver. The hotel's concierge had called the last available taxi driver in town for me. But even this man was now too busy driving tourists around; so he volunteered his father to drive me. I had never before had to rely on someone who could not even guess what

yes

or

no

meant (and head motions don't work here, since in Asia they often mean differentâeven oppositeâthings from what they mean in our culture).

Angkor Conservation, a small, specialized foundation dedicated to the conservation of Cambodian antiquities, is not indicated on any tourist map. So I knew it would be hard to find it under any circumstances, and nearly impossible with a driver who couldn't communicate with me. Fortunately, the concierge at the hotel thought to use his iPhone to find Angkor Conservation. He circled its location on the map he handed me. It was situated by the Siem Reap River, away from the main part of town, and the map showed that the general place he had circled was near an Italian restaurant named Ciao.

I knew this would be hard. I showed the cab driver the map and he grumbled something in Khmer. After a few moments of talking past each other, he decided to move and drove somewhereâI wasn't sure he understood anything. Siem Reap is still a traditional Southeast Asian town, in which cars are relatively rare and most locals use bicycles or, if they are wealthier, motorcycles. Transportation for hire is usually by tuk-tuk. We managed to maneuver our way through a series of traffic jams in which motorcycles and

tuk-tuks competed for road space and ignored the legal direction of traffic.

We made our way through the downtown area and headed north on Charles de Gaulle Boulevard, in the direction of the Angkor Wat complex. After passing the lush tropical gardens belonging to a new hotel, we turned right on a narrow road, once paved but now gravelly and lined with rickety tables set up by scores of vendors hawking fruits and vegetables. We continued toward the river. Then the driver turned right into a dirt road and we bumped along for some time, finally stopping by a small farm with chickens running around in the dusty yard, some of them scattering at the approach of our car. There was nobody around. We both got out and stood there, scratching our heads and staring blankly at a map that seemed to say nothing to either of us.

Some ten minutes later, someone emerged from a shack some distance away and approached us. The driver and the man who came over started an animated discussion apparently about where we were and where we were going; both men soon became very excited, raising their hands up in the air, pointing first in one direction, then in another, their voices rising. Finally, the driver returned to the car and slammed the driver's door. I tried to say, “This can't be right. This is not the place . . .” But he understood nothing, and seemed to care even less. He put the car in reverse and drove backward on the narrow dirt path until we came back to the road. There he just stopped and started talking fast in Khmer, looking at me expectantly.

This is crazy, I thought. I picked up the map. I couldn't make out anythingâand there was no Ciao restaurant anywhere, either.

After trying to find the place while driving slowly back along the road for another half an hour, up and down and scrutinizing both sides, I decided it was time to give up. “Hotel!” I said. He understood. “Hotel,” he said, smiling for the first time since I hired him, “hotel,” and he made the way back double-time, traffic and all.

It was late afternoon, and as I got out of the cab at the Angkor Miracle Resort Hotel's driveway, I noticed five tuk-tuks parked at the entrance, their drivers lazing in the sun by their vehicles. One of them, a boy with a soft, round face who looked 16 or even younger, noticed me and ran over. “Sir,” he said, “please, please hire me; I am a good driver, and I need the money. Please.” The tuk-tuk behind him had in big letters on its side “Mr. Bee.” I dislike tuk-tuks: I find them unsafe since the bed behind the motorcycle engine has no protection at all, generally being made of wood, and the ride is bumpy.

He looked up at me. He was small and thin, his eyes bright and pleading. “Sure, Mr. Bee,” I said. “But the place I am looking for is closed by now.” He looked very disappointed, and his head dropped somewhat; he started to turn to walk away. “Tomorrow,” I said. “I promise, really!”âI knew that these tuk-tuk drivers hear

tomorrow

and know there likely will be nothing: The customer will find something else to do, or another driver. “Be here at eight in the morning, please, and I will hire you for a full dayâI promise.”

Mr. Bee smiled. “I'll be here,” he said. I gave him $2 to show my good faith.

The next morning

before eight, Mr. Bee was there. He saw me from afar as I approached the hotel door and ran over. “Good morning, sir,” he said.

“Good to see you, Mr. Bee,” I answered. Then I showed him the map. “Can you read it?”

“Yes, I can,” he said confidently and we looked it over together. He smiled and said, “I'll take you there,” and he put on his helmetâfew other tuk-tuk drivers use helmets, and I took this as a sign of his being very careful; he would prove himself to be careful, intelligent, and considerate. He helped me into the tuk-tuk's cab. It became clear very quickly that not only did he speak close to perfect English, but this young man, a boy, really, was very brightâfar cleverer than the driver from the day before.

“First, let's go to the Siem Reap Museum,” I said. “And then we'll try to find what I need.” We drove through heavy traffic until we reached the museum. I asked Mr. Bee to wait for a little while outside and went in. “I need to see Mr. Chamroeun Chhan,” I said, “the director.” The woman at the desk asked what it was about. “Mr. Hab Touch sent me to speak with the director about an inscription I am looking for.” She picked up the phone and spoke in Khmer. The only words I understood were “His Excellency Hab Touch.” And then it dawned on me: I had been dealing all along with perhaps the highest official responsible for antiquities in all Cambodiaâsomeone accorded such a lofty honorific. And I realized how ignorant I had been in not understanding what

H. E.

meant in Rotanak's e-mail message about “H. E. Hab Touch.” I was embarrassed that I had not used the proper salutations when communicating with someone who had been so helpful in my quest. Surely His Excellency had many more important things to do than help a random academic looking for an obscure inscription.

Mr. Chamroeun Chhan, on the phone with the person at the desk, soon understood what I was looking for and who had sent me there, but he was away till late afternoon. He said that I should go directly to Angkor Conservation, as Hab Touch had suggested, and see what I could find there. If not, he would meet me at the museum at 5 p.m. I thanked the woman at the desk and went outside the museum and climbed back into Mr. Bee's tuk-tuk.

Mr. Bee made the drive pleasantâhe was able to find the shortest route from the museum to the general area we were going to, east of Charles de Gaulle Boulevard in the vicinity of the pediatric hospital, on the road north from downtown. When we reached the hospital, he signaled me that he was stopping.

“May I see the map again?” he asked. I gave it to him. “We turn here,” he said, “not by Sofitel as you did yesterday.” Sure of what he was doing, he took a barely paved road that ran just parallel to the one we had taken the day before. They were very close and looked the same, with the same street hawkers grazing the sides of each, and the same low bushes by the sides of the road and the same palm trees a little distance away. But the entrance to this road was hidden from the boulevard, and it took a keen eye to discern it.

Mr. Bee signaled with his hand and carefully turned right. He drove slowly, looking searchingly to both sides. About half a mile later, he slowed down. On the left side there was an iron gate with a small sign: “Angkor Conservation.” He blew his horn lightly, and a man walked over and opened the gate just wide enough for a tuk-tuk to enter. We went in, driving over a series of stone slabs. A hundred feet inside were several large sheds and a group of men

sitting outside one of them, making coffee in a copper pot on a little open wood fire. Mr. Bee approached them.

There was a lot of talking in Khmer and gesturing, but the men didn't understand what we wanted. Mr. Bee smiled sheepishly as he came back to me, and raised his hands up in the air as if to say, “I don't get it.”

“Ask them where the director is,” I said. There was more gesturing and words exchanged. Finally one of the workers pointed left. We walked in that direction. About 80 feet ahead of us was a makeshift office. I entered; Bee waited outside. “I am looking for the director,” I said to the woman at the desk. She ignored me. She clearly didn't understand a word. It was very hot inside, the sun beating down on the tin roof even at this time of morning. I stood and waited. Finally, a middle-aged man came in. “Hello,” I said. “His Excellency Hab Touch of the Ministry of Culture sent me here. I am looking for inscription K-127.”

“Hello,” he said. “Yes, he told us you would be coming. Let me take you to where all the old artifacts are, and you can look for it yourself, if it's there at all. You know what happened right here in 1990 . . .”

“Yes,” I said sadly. “The Khmer Rouge came and destroyed much of what you had here. But I hope . . .” He gave a wan smile and motioned me to follow him.

We walked over to a large shed covered in plastic sheeting. “It might be here, somewhere, unless they got it when they plundered this place. You can see what they did.” He pointed toward the edge of the enclosure, where there was a pile of broken stones that once represented statues. It looked depressing and hopeless. Then he just

turned around and went back to his office, leaving me among the rubble and the many standing artifacts.

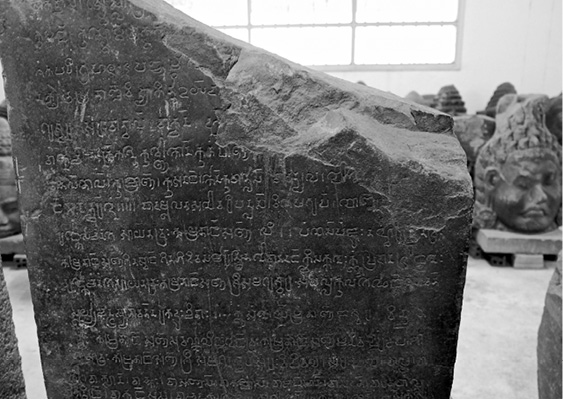

I looked around me, away from the piles of destroyed statues. There were probably thousands of items, including heads of statues from Angkor Watâmany hundreds of them, more than half of them badly damagedâand large stones with inscriptions filling much of the area. I began to walk slowly, from one item to the next, inspecting each. I knew vaguely what K-127 had to look likeâif it still existed and was in one piece. It would have been a slab of red stone, about five feet high and broken at the top. I walked around for an hour, finding nothing. This was frustrating, and I was losing hope.

Then I just sat down on one of the stone inscriptions, wiped my foreheadâit was intensely hot and humid in this deserted, airless shedâand took a drink from my bottle of water. The temperature was surely over 100 degrees. I felt limp and lethargic. Then I forced myself to get up and started examining the stones again. I thought my random search would probably not be effective and decided to look more systematically, row by row. I went back to the entrance and took the first row, going down to the end, and then continuing to the next row, and so on. I searched in this way for another hour, but found nothing.

Finally, I decided to walk

behind

the artifacts. I moved slowly from item to item until I came to a stone that fit the description I had with me. On its back side I saw an old piece of tape pasted to the bottom of the red stone. It read, “K-127.” I could not believe my eyes. Could this be right? Had I really found it?

I looked at the front part of this large reddish stone, and there it wasâI recognized the Khmer numerals: 605. The zero was a

dotâthe first known zero. Was this really it? I read it again. The inscription was remarkably clear. I stood by it feeling euphoric. I wanted to touch it, but dared not. It was a solid piece of carved stone, which had withstood the ravages of 13 centuries and was still as legible and clear and shiny of surface as ever. But I viewed it as fragile and delicate; I felt it was so precious that I dare not breathe on it. Perhaps this was a dream, and if I touched the stone, it would disappear. I'd worked so hard to find it.

This is the Holy Grail of all of mathematics,

I thought.

And I found it.