Finding Zero (5 page)

Authors: Amir D. Aczel

I began my search in south Asia working backward in time, starting with the tenth century CE. The day after my memorable meeting with Raju, I took a yellow-green tuk-tukâthe ubiquitous three-wheeled, motorcycle-powered vehicle that can navigate even the narrowest streets of the most crowded of Asian citiesâthrough Delhi's early-morning mist to the airport. There I boarded a Kingfisher Airlines flight to Khajuraho, a complex of Hindu and Jain temples situated in what was once a dense forest in the state of Madhya Pradesh. After two hours of flight, the Kingfisher stopped at the holy city of Varanasi on the Ganges, where we stayed on the ground for about 20 minutes, and then took off again for Khajuraho, less than an hour away. As we were about to land, I glimpsed stone temples below in the remains of a lush tropical jungle.

A few decades ago, a Japanese mathematician named Takao Hayashi had photographed some mysterious numbers here, but he had no information on the name of the temple where the ancient inscription could be found. I had to discover it for myself.

Khajuraho has a tiny airstrip, and a hut serves as a terminal. I got a cab, a rickety old Ford with no upholstery or much of an interior, smelling of sweat and rotted vegetables. I took it up the straight, dusty road through dried-up, hardscrabble fields to one of just a handful of hotels, a Best Westernâthe nicest place in this tiny town, it turned out. The young man at the desk was not as interested in assigning me my room as in selling me tourist trinkets in his side business. I turned him down and asked for my room keyâI would have no time for shopping, I explained. After checking in, I left the hotel and in about 15 minutes of walking on deserted roads managed to find my way to the temples. A man with apparent signs of leprosy sat on the ground outside the entrance to the fenced compound. I paid the admission fee and entered. Most tourists come here to gawk at the graphic erotic statues and friezes that adorn these unusual temples.

In 1838, a British military officer, Captain T. S. Burt, was exploring the jungles of Madhya Pradesh some 400 miles southeast of New Delhi with his company of Bengal Engineers when he and his men came upon a group of ancient temples that had been reclaimed by the jungle. What they saw stunned Burt. In his logbook, he noted that these temples were among the finest he had ever seen, but he was also at a loss on how to describe the nature of the erotic art he saw at Khajuraho. About 10 percent of all the magnificent, eleventh-century stone statuary here depicted sexual situations, some of which seem startlingly bold even today.

In the West, we don't see sexual imagery in public locationsâcertainly not in places of worship. But the statues Burt saw, of men

and women engaged in a variety of sexual positions, many quite acrobatic and imaginative, were on the outside walls as well as the insides of Hindu and Jain temples built a thousand years ago. Burt wrote in his diary, “I found seven Hindoo temples, most beautifully and exquisitely carved as to workmanship, but the sculptor had at times allowed his subject to grow a little warmer than there was absolute necessity for his doing.”

1

There were once 85 temples at Khajuraho, and 20 of them survive to this day; they are both Hindu and Jain.

All temples in this areaâ“a stone's throw away from each other,” as Burt wroteâhave statues adorning their walls. These sculptures depict scenes from everyday life as well as images of deities. But the erotic scenes strongly dominate these temples because they are so explicit and so unexpected. These are almost life-size statues and friezes carved in gray, yellow, or reddish stone showing people in every imaginable sex act. At one temple, high above the observer, a man and a woman are supported by two seminude women; he is held upward, facing away from the viewer; below him and facing us is the naked woman, her head on the floor; her legs are spread above, and the two of them are attached in their genital region. At another temple, at eye level, there are statues of several elephants led by people, and on the right, unexpectedly, is a statue of a man mounting a woman from behindâoblivious of the elephants. At another temple, an entire panel depicts men and women engaged in several different positions of oral sex, as well as a combined oral and vaginal sex act by one woman with two men.

To date, no good explanation has been proposed for this unusual art. Tour guides lecture about the Kama Sutra to naive tourists who venture here, and magazine articles and tour books suggest that some of the sexually explicit statues represent the Hindu god Shiva and his Shakti, Parvati. The dreaded destroyer of worlds, if this is true, is only interested in his consort's body; and anyway, many of the temples are not Hindu but Jain. Some of the more scholarly sources conjecture that the imagery may have served as fertility symbols. But nobody really knows the answer.

As inexplicable as the erotic art of Khajuraho was, so was the discovery more than a century ago of a piece of complex mathematics in this location. I had gleaned hints of it in an old book on the history of mathematics. David Eugene Smith says, “[A magic square] appears in a Jaina inscription in the ancient town of Khajuraho, India, where various ruins bear records of the Chandel dynasty (870â1200).”

2

I had originally thought that Hayashi might have been led here by this reference; instead, it turned out that he had read the very first historical description of this curious mathematical piece, written much earlier. Hayashi had possessed the actual announcement of the discovery of this ancient magic square in the notes made by the prominent British archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham, who in the 1860s found the mathematical inscription by the entrance to a Jain temple.

3

I spent several hours visiting all the temples of the compound, but nowhere found an inscription. Where was Hayashi's magic square? I asked every tour guide I metânothing. Then a French tourist who had overheard me ask his guide said, “I think I may

have seen some ancient numbers by the door of one of the temples in the Eastern Group.” This was all the way across town, in a more deserted and rarely visited set of temples.

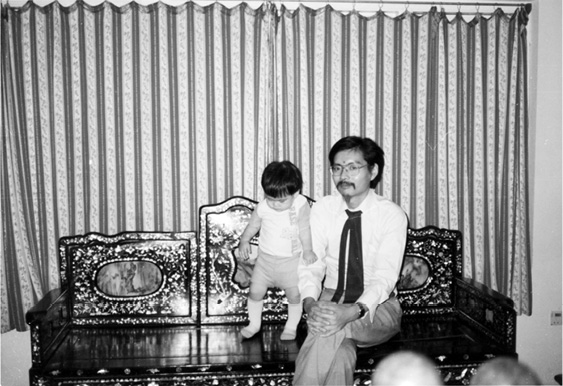

Takao Hayashi in the former summer palace of the Maharaja of Mysore (with his son Makoto) in 1983 while researching the history of mathematics in India.

I left the fenced-off compound and walked for half an hour, passing stray cattle, which roam freely in all Indian towns, feeding on garbage, and finally found the ancient temples composing the Eastern Group. The edifices here were mostly Jain rather than Hindu. I went from one temple to the next, followed by stray dogs and children dressed in rags asking for money. Otherwise, the grounds were eerily deserted. A wind blew in from the fields, kicking up swirls of dust. I saw nothing. Then I came to the Parsvanatha temple, a Jain temple built in the mid-tenth century CE. The doorway was framed with erotic statues. A man, or perhaps a god,

stared amorously into the eyes of the woman or goddess in his arms, her head turned up to him. His left hand fondled her ample breast.

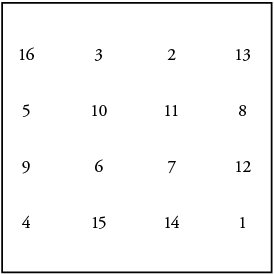

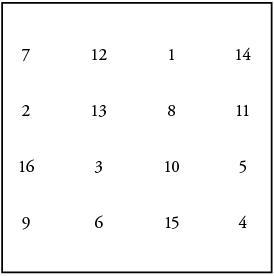

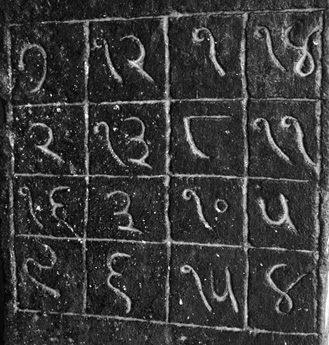

And there on the right, inside the doorway, I finally found what I had come here forâthe numerals Hayashi had seen 40 years earlier but could not remember exactly where. It was a magic square, with Hindu numerals (some of which are like our own and some so different they are not recognizable by a nonexpert), inscribed on the door of this thousand-year-old temple. This magic square was a four-row by four-column square with the following digits (here transcribed using our modern numerals):

Now notice some amazing facts: The sum of every horizontal row is 34; so is the sum of every vertical column, the sums of the two diagonals, the sums of all two-by-two squares at the four corners of the larger square, and also the sum of the central two-by-two square. The temple bearing this curious inscription is definitively dated by another inscription to 954 CE. So as early as the mid-tenth-century, the people who built and worshipped here

understood how to construct such sophisticated magic squares. The Khajuraho magic square is one of the oldest four-by-four squares (earlier three-by-three squares are known in China and Persia).

The magic square at the entrance of the tenth-century Parsvanatha temple at Khajuraho.

With its magic square and numerals found on site, Khajuraho provides the greatest example of Hindu numerals from as early as the tenth century. The numbers found at Khajuraho and at other early temples in India suggest that numbers here may have originated in connection with religious needs and practices. For example, ancient Indian documents called the Vedasâdating from as early as the second millennium BCEâspecify the sizes of temples and the numbers of animals to be sacrificed; all are represented numerically, and it is perhaps for this reason that the earliest Hindu numerals appear in ancient temples.

The decorated façade of one of the ancient temples of Khajuraho.

Also, these numbers have been identified in one of the most curious early documents ever discovered. Interestingly, in 1514, the

German artist Albrecht Dürer, who was fascinated by numbers, made a celebrated engraving called “Melancholia,” which featured at its upper right corner a four-by-four magic square: