Finest Years (17 page)

In September 1940 an Italian army led by Marshal Graziani, 200,000 strong and thus outnumbering local British forces by four to one, crossed the east Libyan frontier and drove fifty miles eastward into Egypt before being checked. Meanwhile in East Africa, Mussolini's troops seized the little colony of British Somaliland and advanced into Kenya and Sudan from their bases in Abyssinia. Wavell ordered Somaliland evacuated after only brief resistance. He remained impenitent in the face of Churchill's anger about another retreat.

This first of Britain's âdesert generals' was much beloved in the army. In World War I, Wavell won an MC and lost an eye at Ypres, then spent 1917-18 as a staff officer in Palestine under Allenby, whose biography he later wrote. A reader of poetry, and prone to introspection, among soldiers Wavell passed as an intellectual. His most conspicuous limitation was taciturnity, which crippled his relationship with Churchill. Many who met him, perhaps over-impressed by his enigmatic persona, perceived themselves in the presence of greatness. But uncertainty persisted about whether this extended to mastery of battlefields, where a commander's strength of will is of greater importance than his cultural accomplishments.

On 28 October 1940, the Italians invaded north-west Greece. Contrary to expectations, after fierce fighting they were evicted by the Greek army and thrown back into Albania, where the rival forces languished in considerable discomfort through five months that followed. British strategy during this period became dominated by Mediterranean dilemmas, among which aid to Greece and offensive action in Libya stood foremost. Churchill constantly incited his C-in-C to take the offensive against the Italians in the Western Desert, using the tanks shipped to him at such hazard during the summer. Wavell insisted that he needed more time. Now, however, overlaid upon this issue was that of Greece, about which Churchill repeatedly

changed his mind. On 27 October, the day before Italy invaded, he dealt brusquely with a proposal from Leo Amery and Lord Lloyd, respectively India and colonial secretaries, that more aid should be dispatched: âI do not agree with your suggestions that at the present time we should make any further promises to Greece and Turkey. It is very easy to write in a sweeping manner when one does not have to take account of resources, transport, time and distance.'

Yet as soon as Italy attacked Greece, the prime minister told Dill that âmaximum possible' aid must be sent. Neville Chamberlain in March 1939 had assured the Greeks of British support against aggression. Now, Churchill perceived that failure to act must make the worst possible impression upon the United States, where many people doubted Britain's ability to wage war effectively. At the outset he proposed sending planes and weapons to Greece, rather than British troops. Dill, Wavell and Edenâthen visiting Cairoâquestioned even this. Churchill sent Eden a sharp signal urging boldness, dictated to his typist under the eye of Jock Colville.

He lay there in his

four-post bed with its flowery chintz hangings, his bed-table by his side. Mrs Hill [his secretary] sat patiently opposite while he chewed his cigar, drank frequent sips of iced soda-water, fidgeted his toes beneath the bedclothes and muttered stertorously under his breath what he contemplated saying. To watch him compose some telegram or minute for dictation is to make one feel that one is present at the birth of a child, so tense is his expression, so restless his turnings from side to side, so curious the noises he emits under his breath. Then out comes some masterly sentence and finally with a âGimme' he takes the sheet of typewritten paper and initials it, or alters it with his fountain-pen, which he holds most awkwardly half way up the holder.

On 5 November Churchill addressed MPs, reporting grave shipping losses in the Atlantic and describing a conversation he had held on his way into the Commons with the armed and helmeted guards at its doors. One soldier offered a timeless British cliché to the prime

minister: âIt's a great life if you don't weaken.' This, Churchill told MPs, was Britain's watchword for the winter of 1940: âWe will think of something better by the winter of 1941.' Then he adjourned to the smoking room, where he devoted himself to an intent study of the

Evening News

, â

as if it were the only source

of information available to him'. Forget for a moment the art of his performance in the chamber. What more brilliant stagecraft could the leader of a democracy display than to read a newspaper in the common room of MPs of all parties, in the midst of a war and a blitz? â “How are you?” he calls gaily to the most obscure Memberâ¦His very presence gives us all gaiety and courage,' wrote an MP. âPeople gather round his table completely unawed.'

Despite Wavell's protests, Churchill insisted upon sending a British force to replace Greek troops garrisoning the island of Crete, who could thus be freed to fight on the mainland. The first consignment of material dispatched to Greece consisted of eight anti-tank guns, twelve Bofors, and 20,000 American rifles. To these were added, following renewed prime ministerial urgings, twenty-four field guns, twenty anti-tank rifles and ten light tanks. This poor stuff reflected the desperate shortage of arms for Britain's soldiers, never mind those of other nations. Some Gladiator fighters, capable of taking on the Italian air force but emphatically not the Luftwaffe, were also committed. Churchill was enraged by a cable from Sir Miles Lampson, British ambassador in Egypt, dismissing aid to Greece as âcompletely crazy'. The prime minister told the Foreign Office: âI expect to be protected from this kind of insolence.' He dispatched a stinging rebuke to Lampson: â

You should not telegraph

at Government expense such an expression as “completely crazy” when applied by you to grave decisions of policy taken by the Defence Committee and the War Cabinet after considering an altogether wider range of requirements and assets than you can possibly be aware of.'

On the evening of 8 November, however, the prospect changed again. Eden returned from Cairo to confide to the prime minister first tidings of an offensive Wavell proposed to launch in the Western Desert the following month. This was news Churchill craved: â

I purred like six cats

.'

Ismay found him ârapturously happy'. The prime minister exulted: â

At long last we are

going to throw off the intolerable shackles of the defensive. Wars are won by superior will-power. Now we will wrest the initiative from the enemy and impose our will on him.' Three days later, he cabled Wavell: âYou mayâ¦be assured that you will have my full support at all times in any offensive action you may be able to take against the enemy.' That same night of 11 November, twenty-one Swordfish biplane torpedo bombers, launched from the carrier

Illustrious

, delivered a brilliant attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto which sank or crippled three battleships. Britain was striking out.

Churchill accepted that the North African offensive must now assume priority over all else, that no troops could be spared for Greece. A victory in the desert might persuade Turkey to come into the war. His foremost concern was that Wavell, whose terse words and understated delivery failed to generate prime ministerial confidence, should go for broke. Dismayed to hear that Operation

Compass

was planned as a limited âraid', Churchill wrote to Dill on 7 December: â

If, with the situation as it is

, General Wavell is only playing small, and is not hurling in his whole available forces with furious energy, he will have failed to rise to the height of circumstancesâ¦I never “worry” about action, but only about inaction.'

He advanced a mad notion

, that Eden should supplant Wavell as Middle East C-in-C, citing the precedent of Lord Wellesley in India during the Napoleonic wars. Eden absolutely refused to consider himself for such an appointment.

On 9 December, at last came the moment for the âArmy of the Nile', as Churchill had christened it, to launch its assault. Wavell's 4th Indian and 7th Armoured Divisions, led by Lt.Gen. Sir Richard O'Connor, attacked the Italians in the Western Desert. Operation

Compass

achieved brilliant success. Mussolini's generals showed themselves epic bunglers. Some 38,000 prisoners were taken in the first three days, at a cost of just 624 Indian and British casualties. âIt all seems too good to be true,' wrote Eden on 11 December. Wavell decided to exploit this success, and gave O'Connor his head. The little

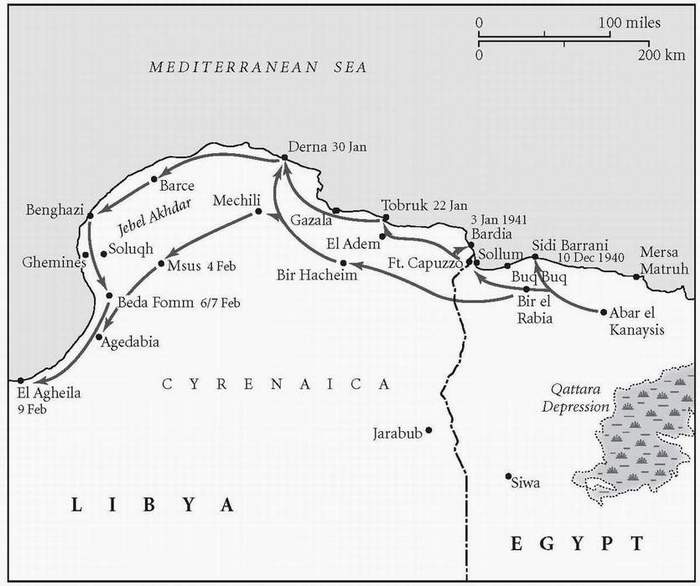

British army, by now reinforced by 6th Australian Division, stormed along the coast into Libya, taking Bardia on 5 January. At 0540 on 21 January 1941, red Verey lights arched into the sky to signal the start of O'Connor's attack on the port of Tobruk. Bangalore torpedoes blew gaps in the Italian wire. An Australian voice shouted: âGo on, you bastards!'

At 0645, British tanks lumbered forward. The Italians resisted fiercely, but by dawn next day the sky was lit by the flames of their blazing supply dumps, prisoners in thousands were streaming into British cages, and the defenders were ready to surrender. O'Connor dispatched his tanks on a dash across the desert to cut off the retreating Italians. The desert army was in a mood of wild excitement. â

Off we went across

the unknown country in full cry,' wrote Michael Creagh, one of O'Connor's division commanders. In a rare exhibition of emotion, O'Connor asked his chief of staff: âMy God,

do you think it's going to be all right?' It was indeed âall right'. The British reached Beda Fomm ahead of the Italians, who surrendered. In two months, the desert army had advanced 400 miles and taken 130,000 prisoners. On 11 February another of Wavell's contingents advanced from Kenya into Abyssinia and Somaliland. After hard fightingâmuch tougher than in Libyaâhere too the Italians were driven inexorably towards eventual surrender.

For a brief season, Wavell became a national hero. For the British people in the late winter and early spring of 1940-41, battered nightly by the Luftwaffe's bombardment, still fearful of invasion, conscious of the frailty of the Atlantic lifeline, success in Africa was precious. It was Churchill's delicate task to balance exultation about a victory with caution about future prospects. Again and again in his broadcasts and speeches he emphasised the long duration of the ordeal that must lie ahead, the need for unremitting exertion. To this purpose he continued to stress the danger of a German landing in Britain: in February 1941 he demanded a new evacuation of civilian residents from coastal areas in the danger zone.

Churchill knew how readily the nation could lapse into inertia. The army's home forces devoted much energy to anti-invasion exercises, such as

Victor

in March 1941.

Victor

assumed that five German divisions, two armoured and one motorised, had landed on the coast of East Anglia. On 30 March, presented with a report on the exercise, Churchill minuted mischievously, but with serious intent: âAll this data would be most valuable for our future offensive operations. I should be very glad if the same officers would work out a scheme for our landing an exactly similar force on the French coast.' Even if no descent on France was remotely practicable, Churchill was at his best in pressing Britain's generals again and again to forswear a fortress mentality.

But public fear and impatience remained constants. â

For the first time

the possibility that we may be defeated has come to many peopleâme among them,' wrote Oliver Harvey, Eden's private secretary, on 22 February 1941. â

Mr Churchill's speech

has rather sobered me,' wrote London charity worker Vere Hodgson after a prime minis

terial broadcast that month. âI was beginning to be a little optimistic. I even began to think there might be no Invasionâ¦but he thinks there will, it seems. Also I had a feeling the end might soon be in sight; he seems to be looking a few years ahead! So I don't know what is going to happen to us. We seem to be waitingâwaiting, for we know not what.'

Churchill had answers to Miss Hodgson's question. â

Here is the hand

that is going to win the war,' he told guests at Chequers, who included Duff Cooper and General Sikorski, one evening in February. He extended his fingers as if displaying a poker hand: âA Royal FlushâGreat Britain, the Sea, the Air, the Middle East, American aid.' Yet this was flummery. British successes in Africa promoted illusions that were swiftly shattered. Italian weakness and incompetence, rather than British strength and genius, had borne O'Connor's little force to Tobruk and beyond. Thereafter, Wavell's forces found themselves once more confronted with their own limitations, in the face of energetic German intervention.

In the autumn of 1940 Hitler had declared that ânot one man and not one pfennig' would he expend in Africa. His strategic attention was focused upon the East. Mussolini, with his ambition to make the Mediterranean âan Italian lake', was anyway eager to achieve his own conquests without German aid. But when the Italians suffered humiliation, Hitler was unwilling to see his ally defeated, and to risk losing Axis control of the Balkans. In April he launched the Wehrmacht into Yugoslavia and Greece. An Afrika Korps of two divisions under Erwin Rommel was dispatched to Libya. A new chapter of British misfortunes opened.