Finest Years (46 page)

he summoned his country he has borne a leader's share.' Dalton wrote on 12 November: â

The self-respect of the British Army

is on the way to being re-established. Last weekâ¦a British general was seen to rush in front of a waiting queue at a bus stop and to leap upon the moving vehicle. One onlooker said he would not have dared to do this a week before.'

Alexander and Montgomery became Britain's military heroes of the hour, and indeed of the rest of the war. The former was especially fortunate to find laurels conferred upon him, for his talents were limited. Hereafter, Alexander basked in Churchill's favour. He conformed to the prime minister's

beau idéal

of the gentleman warrior. While forces under his command would endure many

setbacks, they never suffered absolute defeat. Montgomery was a much more impressive personality, a superb manager and trainer of troops, the first important British commander to display the steel necessary to fight the Germans with success. Churchill famously observed of him: â

Pity our 1st victorious general

should be a bounder of the 1st water.' Montgomery's conceit was notorious. In one of his proclamations in the wake of a victory, he asserted that it had been achieved âwith the help of God'. In the âRag', an officer observed sardonically that â

It was nice Monty

had at last mentioned the Almighty in dispatches.' Yet Churchill and Brooke knew that diffidence and modesty are seldom found in successful commanders. Montgomery had few, if any, of the attributes of a gentleman. This was all to the good, even if it rendered him less socially congenial to the prime minister than Alexander. Gentlemen had presided over too many British disasters.

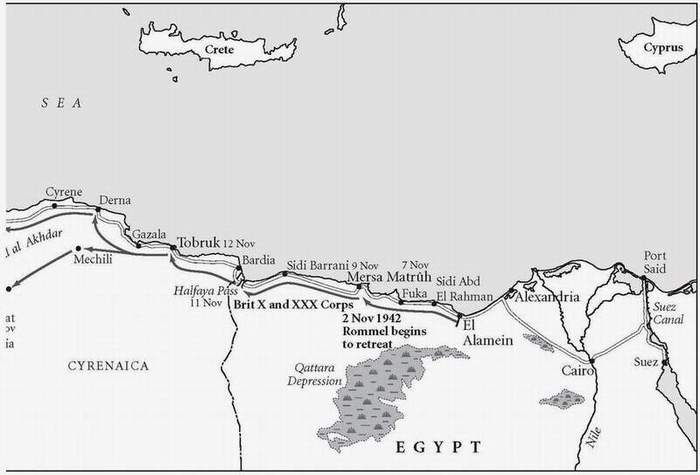

âMonty's' cold professionalism was allied to a shrewd understanding of what could, and could not, be demanded of a British citizen army in whose ranks there were many men willing to do their duty, but few who sought to become heroes. He does not deserve to rank among history's great captains, but he was a notable improvement upon the generals who had led Britain's forces in the first half of the Second World War. A carapace of vanity armoured him against prime ministerial harrowing of the kind that so wounded Wavell and Auchinleck. In the autumn and winter of 1942 it was the newcomers' good fortune to display adequacy at a time when the British achieved a formidable superiority of men, tanks, aircraft.

â

We are winning victories!

' exulted London charity worker Vere Hodgson on 29 November. âIt is difficult to get used to this state of things. Defeats we don't mindâwe have all developed a stoical calm over such things in England. But actually to be advancing! To be taking places! One has an uneasy sense of enjoying a forbidden luxury.' Aneurin Bevan said nastily that the prime minister âalways refers to a defeat or a disaster as though it came from God, but to a victory as though it came from himself'. Throughout the war, Bevan upheld

Britain's democratic tradition by sustaining unflagging criticism of the government. To those resistant to Welsh oratory, however, his personality was curiously repellent. A dogged class warrior, he harried Churchill across the floor of the Commons as relentlessly when successes were being celebrated as when defeats were lamented. Bevan drew attention to the small size of the forces engaged at Alamein, and to the dominance of Commonwealth troops in Montgomery's army. His figures were accurate, but his scorn was at odds with the spirit of the momentâfull of gratitude, as was the prime minister. At a cabinet meeting on 9 November, Churchill offered the govern-ment's congratulations to the CIGS and Secretary of State for the army's performance. This was, wrote Brooke sourly later, â

the only occasion on which

he expressed publicly any appreciation or thanks for work I had done during the whole of the period I worked for him'.

For a generation after the Second World War, when British perceptions of the experience were overwhelmingly nationalistic, Alamein was seen as the turning point of the conflict. In truth, of course, Stalingradâwhich reached its climax a few weeks laterâwas vastly more important. Montgomery took 30,000 German and Italian prisoners in his battle, the Russians 90,000 in theirs, which inflicted a quarter of a million losses on Hitler's Sixth Army. But Alamein was indeed decisive for Britain's prime minister. On 22 November he felt strong enough to allow Stafford Cripps to resign from the war cabinet, relegating him to the ministry of aircraft production. Churchill said of Cripps to Stalin: âHis chest is a cage, in which two squirrels are at war, his conscience and his career.' Cripps had pressed proposals for removing the direction of the war from the prime minister's hands. Now these could safely be dismissed, their author sidelined. His brief imposture as a rival national leader was over. In the ensuing thirty months of the German war, though the British people often grew jaded and impatient, never again was Churchill's mastery seriously questioned.

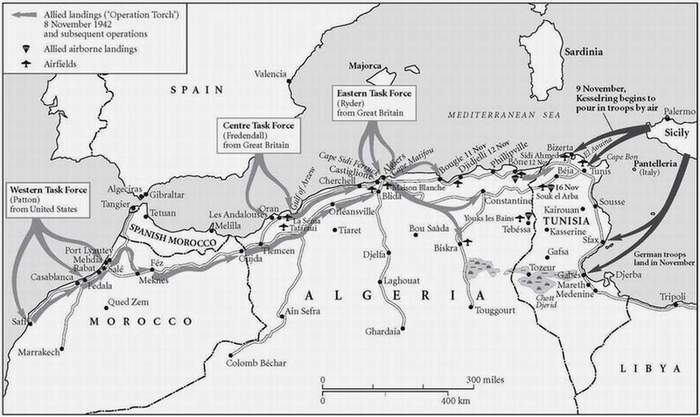

As Montgomery's forces continued to drive west across Libya, the prime minister looked ahead. Fortified by Ultra-based intelligence, he felt confident that the combination of Eighth Army's victory at

Alamein and the

Torch

landings ensured the Germans' expulsion from North Africa. No more than anyone else did he anticipate Hitler's sudden decision to reinforce failure, and the consequent prolongation of the campaign. In November 1942 it seemed plausible that the entire North African littoral would be cleared of the enemy by early new year. What, then, for 1943? The chiefs of staff suggested Sicily and Sardinia. This prompted a contemptuous sally from Downing Street: â

Is it really to be supposed

that the Russians will be content with our lying down like this during the whole of 1943, while Hitler has a third crack at them?' Churchill talked instead of possible landings in Italy or southern France, perhaps even north-west Europe. Though he soon changed his mind, in November he still shared American hopes for

Roundup

, a major invasion of the Continent in 1943. He also remained mindful of his commitments to Stalin, and was acutely anxious not to be seen again to break faith. He told the War Office on 23 November: â

I never meant the Anglo-American

Army to be stuck in North Africa. It is a springboard and not a sofa.'

The Americans were often unjust in supposing that Churchill shared the extreme caution of his generals. On the contrary, the prime minister was foremost among those urging commanders to act more boldly. As he told the House of Commons on 11 November, âI am certainly not one of those who need to be prodded. In fact, if anything, I am a prod. My difficulties rather lie in finding the patience and self-restraint through many anxious weeks for the results to be achieved.' For most of the Second World War, Churchill was obliged to struggle against his military advisers' fear of battlefield failure, which in 1942 had become almost obsessive. Alan Brooke was a superbly gifted officer, who forged a remarkable partnership with Churchill. But if Allied operations had advanced at a pace dictated by the War Office, or indeed by Brooke himself, the conflict's ending would have come much later than it did. The British had grown so accustomed to poverty of resources, shortcomings of battlefield performance, that it had become second nature for them to fear the worst. Churchill himself, by contrast, shared with the Americans a

desire to hasten forward Britain's creaky military machine. It was not that Britain's top soldiers were unwilling to fightâlack of courage was never the issue. It was that they deemed it prudent to fight slowly. Oliver Harvey noted on 14 November, with a cynicism that would have confirmed Stalin in all his convictions: â

The Russian army having played

the allotted role of killing Germans, our Chiefs of Staff think by 1944 they could stage a general onslaught on the exhausted animal.'

This was an important and piercing insight upon British wartime strategy from 1942 onwards. There was a complacency, here explicitly avowed by Harvey, about the bloodbath on the eastern front. Neither Churchill nor Brooke ever openly endorsed the expressed desire of colleagues to see the Germans and Soviets destroy each other. But they certainly wanted the vast attritional struggle in the east to spare the Western Allies from anything similar. Most nations in most wars have no option save to engage an adversary confronting them in the field. The Anglo-Americans, by contrast, were quarantined from their enemies by eminently serviceable expanses of water, which conferred freedom of choice about where and when to join battle. This privilege was exercised wisely, from the viewpoint of the two nations. The lives of their young men were diligently husbanded. But such self-interested behaviour, almost as ruthless as Moscow's own, was bound to incur Russian anger.

The Allied invasion of French colonial Africa provoked a political crisis. By chance Admiral Jean Darlan, Vichy vice-president and foreign minister, was in Algiers when the Americans arrived. He assumed command of French forces which, to the surprise and dismay of US commanders, resisted their would-be liberators with considerable energy, killing some 1,400 Americans. There was then a negotiation, however, which caused Darlan to order his troops to lay down their arms, saving many more American lives. He was rewarded by Eisenhower, Allied supreme commander of

Torch

, with recognition as France's high commissioner,

de facto

ruler of North Africa. The British, unconsulted, were stunned. Darlan had collaborated enthusiastically with the Germans since 1940. It had seemed plausible that he might lead the French navy against BritainâDe Gaulle thought

so. â

La France ne marchera pas

,

' he told Churchill, â

mais la flotteâpeut-être

';

â

France will not march [on Britain]. But the fleetâperhaps.' Now, Darlan's betrayal of Vichy demonstrated his moral bankruptcy. In his new role he rejected requests for the liberation of Free French prisoners in North African jails, and indeed treated such captives with considerable brutality. Many exiled Frenchmen missed a great opportunity in November 1942 to sink their differences and throw themselves wholeheartedly into the struggle against the Axis. A British senior officer wrote aggrievedly: â

Although the French

hate the Germans, they hate us more.' De Gaulle, Britain's anointed representative of âFighting France', was of course outraged by the Darlan appointment, as was Eden. The Foreign Office had supported its lofty French standard-bearer through many outbursts of Churchillian exasperation, and in the face of implacable American hostility.

Throughout Churchill's life he displayed a fierce commitment to France. He cherished a belief in its greatness which contrasted with American contempt. Roosevelt perceived France as a decadent imperial power which had lacked British resolution in 1940. Entirely mistakenly, given the stormy relationship between De Gaulle and Churchill, the president thought the general a British puppet. He was determined to frustrate any attempt to elevate De Gaulle to power when the Allies liberated France. The Americans had none of the visceral hatred for Vichy that prevailed in London. Since 1940 they had sustained diplomatic relations with Pétain's regime, which in their eyes retained significant legitimacy. Here was a further manifestation of British sensitivities born of suffering and proximity, while the US displayed a detachment rooted in comfortable inviolability.

In November 1942, British political and public opinion reacted violently to Darlan's appointment. Just as the country was denied knowledge of Stalin's excesses, so it had been told nothing of De Gaulle's intransigence. British people knew only that the general was a patriot who had chosen honourable exile in London, while Darlan was a notorious anglophobe and lackey of the Nazis. When Churchill addressed a secret session of the Commons about the North African crisis on 10 December, the mood of MPs was angry

and uncomprehending. In private, since Darlan's appointment on 8 November Churchill had wavered. He disliked the admiral intensely. But he was also weary of De Gaulle's tantrums. He deemed the solidarity of the Anglo-American alliance to transcend all other considerations. He spoke to the House with remarkable franknessâsuch frankness, indeed, that after the war much of what he said was omitted from the published record of his speeches to the Commons' secret sessions.