Finest Years (65 page)

In truth, however, the British people were much shaken by the

V1 offensive. They were almost four years older, and incomparably more tired, than they had been during the blitz of 1940. The monstrous impersonality of the doodlebugs, striking at all hours of day and night, seemed a refinement of cruelty. Mrs Lylie Eldergill, an East Londoner, wrote to a friend in America: â

I do hope it will soon

be ended. My nerves can't take much more.' Brooke was disgusted by the emotionalism of Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary: â

He kept on repeating

that the population of London could not be asked to stand this strain after 5 years of warâ¦It was a pathetic performance.' The bombardment severely affected industrial production in target areas. In the first week, 526 civilians were killed, and thereafter the toll mounted. It was a godsend to morale that Rome's fall and D-Day had taken place before the V1 offensive began. Hitler made an important mistake by wasting massive resources on his secret weapons programme. The V1s and subsequent V2 rockets were marvels of technology by the standards of the day, but their guidance was too imprecise, their warheads too small, to alter strategic outcomes. The V-weapons empowered the Nazis merely to cause distress in Britain. They might have inflicted more serious damage by targeting the Allied beachhead in Normandy.

Macmillan described Churchill one evening at Chequers, around this time: âSitting in the drawing-room about six o'clock [he] said: “I am an old and weary man.

I feel exhausted

.” Mrs Churchill said, “But think what Hitler and Mussolini feel like!” To which Winston replied, “Ah, but at least Mussolini has had the satisfaction of murdering his son-in-law [Count Ciano].” This repartee so pleased him that he went for a walk and appeared to revive.' One of Brooke's most notorious diary entries about the prime minister was written on 15 August:

We have now reached

the stage that for the good of the nation and for the good of his own reputation it would be a godsend if he could disappear out of public life. He has probably done more for this country than any other human being has ever done, his reputation has reached its climax, it would be a tragedy to blemish such a past

by foolish actions during an inevitable decline which has set in during the past year. Personally I have found him almost impossible to work with of late, and I am filled with apprehension as to where he may lead us next.

Yet if Churchill was indeed old, exhausted and often wrong-headed, he was unchallengeable as Britain's war leader, and Brooke diminished himself by revealing such impatience with him. The prime minister possessed a stature which lifted the global prestige of his country far beyond that conferred by its shrinking military contribution. Jock Colville wrote: â

Whatever the PM's shortcomings

may be, there is no doubt that he does provide guidance and purpose for the Chiefs of Staff and the F.O. on matters which, without him, would often be lost in the maze of inter-departmentalism or frittered away by caution and compromise. Moreover he has two qualities, imagination and resolution, which are conspicuously lacking among other Ministers and among the Chiefs of Staff. I hear him much criticised, often by people in close contact with him, but I think much of the criticism is due to the inability to see people and their actions in the right perspective when one examines them at quarters too close.' All this was profoundly true.

Even in the last phase of the war, when American dominance became painfully explicit, Churchill fulfilled a critical role in sustaining the momentum of his nation. After D-Day, but for the prime minister's personal contribution, Britain would have become a backwater, a supply centre and aircraft-carrier for the American-led armies in Europe. On the battlefield there was considerable evidence that the British Army was once more displaying its limitations. The war correspondent Alan Moorehead, who served through the desert, Italy and into Normandy, enjoyed a close relationship with Montgomery. His view was noted after the war in terse notes made by Forrest Pogue: âBy July, the American soldier better than the British soldier. Original Englishâ¦came from divisions which had been much bled. In first few days [I] went with Br. tanks. They stopped at every bridge because there might be an 88 around.' These strictures might be a little harsh,

but the Americans were not wrong in thinking the British, after five years of war, more casualty-averse than themselves.

In 1944-45 Churchill exercised much less influence upon events than in 1940-43. But without him, his country would have seemed a mere exhausted victim of the conflict, rather than the protagonist which he was determined that Britain should be seen to remain, until the end. âSo far as it has gone,' Churchill told the Commons, âthis is certainly a glorious story, not only liberating the fields of France after atrocious enslavement but also uniting in bonds of true comradeship the great democracies of the West and the English-speaking peoples of the worldâ¦Let us go on, then, to battle on every frontâ¦Drive on through the storm, now that it reaches its fury, with the same singleness of purpose and inflexibility of resolve as we showed to the world when we were alone.' And so he himself sought to do.

Bargaining with an Empty Wallet

For Churchill, the weeks that followed D-Day were dominated by further fruitless wrangles with the Americans.

Roosevelt sent him

a headmasterly rebuke, drafted by Cordell Hull, for appearing to concede to the Russians a lead role in Romanian affairs, in return for Soviet acquiescence in British dominance of Greece. To the Americans, this attitude reflected the deplorable British enthusiasm for bilaterally agreed spheres of influence. Churchill replied irritably next day: âIt would be quite easy for me, on the general principle of slithering to the left, which is so popular in foreign policy, to let things rip, when the King of Greece would probably be forced to abdicate and [the communists of] EAM would work a reign of terrorâ¦I cannot admit that I have done anything wrong in this matter.' If Roosevelt proposed to take umbrage about British failure to inform the White House about every cable to Stalin about Greece and Romania, then what of US messages to Moscow concerning Poland, which the British were not made party to? Churchill ended sadly: â

I cannot think of

any moment when the burden of the war has lain more heavily upon me or when I have felt so unequal to its ever-more entangled problems.'

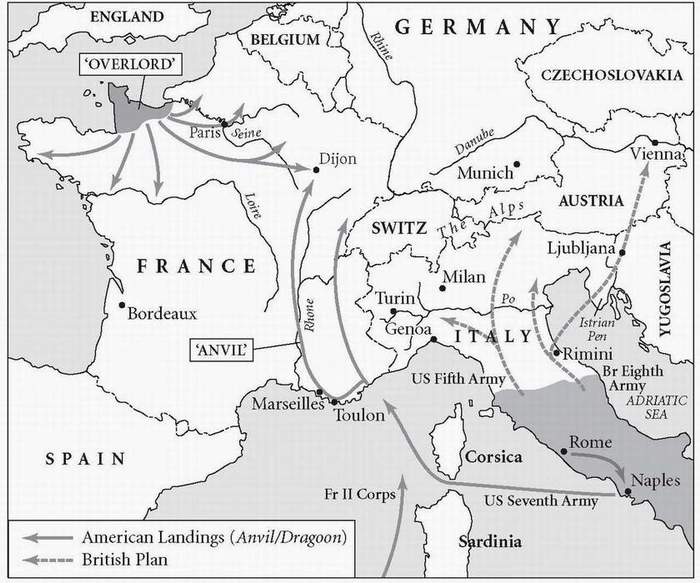

The prime minister still favoured landings on the Atlantic coast of France instead of

Anvil

and, even more dramatically, a major assault on Istria, the north-east Italian coast beyond Trieste, to take place in September. Brooke was cautious about this, warning that the terrain might favour the defence, and could precipitate a winter campaign in the Alps. But the chiefs and their master were

galvanised by an intercepted 17 June German signal. In this Hitler declared his determination to hold Apennine positions as âthe final blocking line' to prevent the Allies from breaking into the north Italian plain of the Po. Here, in British eyes, was compelling evidence of the German commitment to Italy, and thus of the value of contesting mastery there. The Americansâboth Eisenhower and the US chiefsâwere unimpressed. There followed one of the most acrimonious Anglo-American exchanges of the war.

The British chiefs insisted that it was âunacceptable' for more Allied forces to be withdrawn from Italy. Eisenhower, as supreme commander, reasserted his commitment to the landings in southern France, and even more strongly rejected British notions, propounded in a plan drawn up by Maitland-Wilson as Mediterranean C-in-C, for a drive from north-east Italy to the so-called âLjubljana gap'. On 20 June, Ike wrote to Marshall that Maitland-Wilson's plan âseems to discount the fact that Combined Chiefs of Staff have long ago decided to make Western Europe the base from which to conduct decisive operations against Germany. To authorise any departure from this sound decision seems to me ill-advised and potentially dangerousâ¦In my opinion to contemplate wandering off overland via Trieste to Ljubljana repeat Ljubljana is to indulge in conjecture to an unwarrantable degreeâ¦I am unable to repeat unable to see how over-riding necessity for exploiting the early success of

Overlord

is thereby assisted.' The American chiefs signalled on 24 June that Maitland-Wilson's Trieste plan was âunacceptable'. They confirmed their insistence that the planned three US and seven French divisions earmarked for

Anvil

should be withdrawn from Italian operations.

Ill-advisedly, Churchill appealed against this decision to Roosevelt, while on 26 June the British chiefs of staff reaffirmed in a signal to their counterparts in Washington the âunacceptability' of the redeployment. Marshall remained immovable. On the 28th, Churchill dispatched a note to the president in which he wrote: â

Whether we should ruin

all hopes of a major victory in Italy and all its fronts

and condemn ourselves to a passive role in that theatre, after having broken up the fine Allied army which is advancing so rapidly through the peninsula, for the sake of “

Anvil

”with all its limitations, is indeed a grave question for His Majesty's Government and the President, with the Combined Chiefs of Staff, to decide.' He himself, he said, was entirely hostile to

Anvil

. Next day, Roosevelt rejected Churchill's message: âMy interests and hopes,' he said, âcentre on defeating the Germans in front of Eisenhower and driving on into Germany, rather than on limiting this action for the purpose of staging a full major effort in Italy.' Roosevelt added, in the midst of his own re-election campaign, that there were also political implications: â

I should never survive

even a slight setback in “

Overlord

” if it were known that fairly large forces had been diverted to the Balkans.'

Amazingly, Churchill returned to the charge. In a message to Roosevelt on 1 July, after a long exposition of the futility of

Anvil

ââThe splitting up of the campaign in the Mediterranean into two operations neither of which can do anything decisive, is, in my humble and respectful opinion, the first major strategic and political error for which we two have to be responsible'âhe concluded: â

What can I do

Mr President, when your Chiefs of Staff insist on casting aside our Italian offensive campaign, with all its dazzling possibilitiesâ¦when we are to see the integral life of this campaign drained off into the Rhone Valley?â¦I am sure that if we could have met, as I so frequently proposed, we should have reached a happy agreement.' This was woeful stuff. It was supremely tactless for the prime minister to suggest to the president that, if he had been able to browbeat him face to face, he might have persuaded him to override his own chiefs of staff. To the British chiefs he expressed contempt for their American counterparts: â

The Arnold-King-Marshall combination

is one of the stupidest strategic teams ever seen. They are good fellows and there is no need to tell them this.'

The Americans were unmoved by the barrage of cables from London. The British, with icy formality, acceded to the launch of

Anvil

ânow renamed

Dragoon

âon 15 August. This was the moment at which

Churchill perceived his own flagging influence upon the US president, and thus upon his country. â

Up till

Overlord

,' wrote Jock Colville later, âhe saw himself as the supreme authority to whom all military decisions were referred.' Thereafter, he became, âby force of circumstances, little more than a spectator'. The prime minister afterwards told Moran: â

Up to July 1944 England

had a considerable say in things; after that I was conscious that it was America who made the big decisions.'

The British adopted a stubbornly proprietorial attitude to the Italian campaign long after it had turned sour, and even after the dazzling success of

Overlord

. Marshall had made his share of mistakes in the course of the warâbut so had Brooke and Churchill. Nothing in the summer exchanges between London and Washington justified the prime minister's condescension towards the US chiefs. Eisenhower is often, and sometimes justly, criticised for lack of strategic imagination, though he and Marshall were assuredly right to insist upon the concentration of force in France.

Yet it was hard for Churchill to bow to the relegation of himself and his country from the big decisions. An American political scientist, William Fox, coined the word âsuperpower' in 1944. He took it for granted that Britain could be counted as one. The true measure of superpowerdom, however, is a capability to act unilaterally. This, Churchill's nation had lost. Dismay and frustration showed in his temper. Eden wrote on 6 July: â

After dinner a really ghastly

defence committee nominally on Far Eastern strategy. We opened with a reference from W. to American criticism of Monty for over-caution, which W. appeared to endorse. This brought explosion from CIGS.' Brooke wrote in his own diary:

A frightful meeting

with Winston which lasted until 2am!! It was quite the worst we have had with him. He was very tired as a result of his speech in the House concerning the flying bombs, he had tried to recuperate with drink. As a result he was in a maudlin, bad-tempered, drunken mood, ready to take offence at anything, suspicious of everybody, and in a highly vindictive mood against the Americans. In fact so vindictive that his whole outlook on strategy was warped. I began by having a bad row with him. He began to abuse Monty because operations were not going fasterâ¦I flared up and asked him if he could not trust his generals for 5 minutes instead of continuously abusing them and belittling themâ¦He then put forward a series of puerile proposals, such as raising a Home Guard in Egypt to provide a force to deal with disturbances in the Middle East. It was not until midnight that we got onto the subject we had to come to discuss, the war in the Far East!â¦He finished by falling out with Attlee and having a real good row with him concerning the future of India! We withdrew under cover of this smokescreen just on 2am, having accomplished nothing beyond losing our tempers and valuable sleep!!

Eden commented later: â

I called this “a deplorable evening”

, which it certainly was. Nor could it have happened a year earlier; we were all marked by the iron of five years of war.' Accounts like that of Brooke, describing such passages of arms with Churchill, dismayed

those who loved the prime minister, both his personal staff and family, when they were published in the next decade. The prime minister's former intimates took special exception to criticisms that his conduct of office was adversely affected by alcohol. The CIGS was coupled with Lord Moran, whose diary appeared in 1966, not only as a betrayer of the Churchillian legend, but also as a false witness about his conduct. Yet the two men's views were widely shared. After listening to the prime minister for a time at a committee meeting, Woolton leaned over and whispered to Dalton like a naughty schoolboy: â

He is very tight

.' Exhaustion and frustration probably influenced Churchill's outbursts more than brandy. But the evidence is plain that in 1944-45 he suffered increasingly from loss of intellectual discipline, sometimes even of coherence.

The pugnacity that had served his country so wonderfully well in earlier years became distressing when directed against his own colleagues, men of ability and dedication who knew that they did not deserve to be so brutally handled. Churchill could rouse his extraordinary powers on great occasions, of which some still lay ahead. There would be many more flashes of wit and brilliance. But key figures in Britain's war leadership, instead of looking directly to him as the fount of all decisions, were now peering over his shoulder towards a future from which they assumed that he would be absent. Eden, craving the succession, chafed terribly when the prime minister seemed unwilling to acknowledge his own political mortality. â

Lunched alone with W

,' he wrote on 17 July. âHe was in pretty good spirits. My face fell when he said that when coalition broke up we should have two or three years of opposition and then come back together to clear up the mess!'

Yet there were still many moments when Churchill won hearts, including that of the Foreign Secretary, by displays of whimsy and sweetness.

On 4 August, when Eden

called in at Downing Street with his son Nicholas, on holiday from Harrow school, the prime minister surreptitiously slipped into the boy's hand two pound notes, more than a fortnight's pay for an army private, with a muttered and of course vain injunction not to tell â

him

'. Churchill's companions became bored

when he recited long extracts from

Marmion

and

The Lays of Ancient Rome

across the dinner table at Chequers, but how many other national leaders in history could have matched such performances? He was moved to ecstasies by a screening of Laurence Olivier's new film of

Henry V

, not least because he was in no doubt about who was playing the king's part in England's comparable mid-twentieth-century epic. His impatience remained undiminished. Driving with Brooke from Downing Street to Northolt, their convoy encountered a diversion for road repairs. Churchill insisted on lifting the barriers and urging the cars along a footpath. The King himself would never do such a thing, the miscreant declared gleefully, for â

he was

far

more law-abiding

'.

As for the war, by late summer 1944 the apprehension which dogged Churchill and his service chiefs through the spring was now supplanted by assurance that Germany's doom was approaching. But when? On this, the prime minister displayed better judgement than the generals. Until the end of September, they envisaged a final Nazi collapse by the turn of the year. Churchill, by contrast, told a staff conference on 14 July: â

Of course it was true

that the Germans were now faced with grave difficulties and they might give up the struggle. On the other hand, such evidence as there was seemed to show that they intended to continue that struggle, and he believed that if they tried to do so, they should be able to carry on well into next year.' His view remained unchanged even after the drama of the failed bomb plot against Hitler on 20 July. This highlighted German internal opposition to Hitlerâand its weakness.