Fire and Rain (29 page)

Authors: David Browne

John, Yoko and British anti-war leader Michael X auction off the Lennons' cut hair (and a pair of Muhammad Ali's bloodied boxing shorts) at one of the Lennons' many media events throughout 1970. (Bettmann/Corbis)

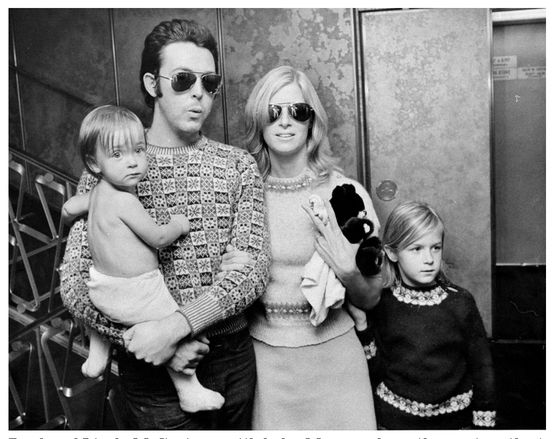

Paul and Linda McCartney with baby Mary and Heather out on the town in New York, October 8. (James Garrett/New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

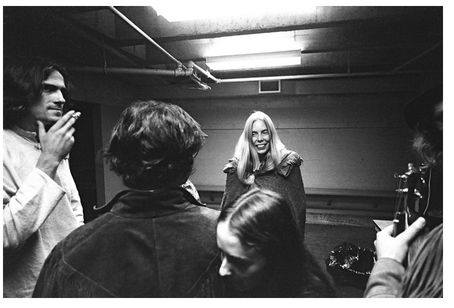

James Taylor keeps tabs on Joni Mitchell and her fans, backstage at the first Greenpeace benefit, October 16. (© Alan Katowitz 2011, all rights reserved)

Â

But since they'd been rehearsing the song all day at the soundstage, the recording was remarkably efficient. In two takes with no overdubbing, they had a finished track; even Crosby's improvised finale, pained screams of “Four, how many more,” was live. The recording, particularly the interplay between Young's twisty opening guitar figure and Stills' coiled-up leads, had a crackling energy and group dynamic rarely heard on

Déjà vu

. When it was done, they gathered around four microphones and recorded a B-side, Stills' “Find the Cost of Freedom,” written but rejected for the

Easy Rider

soundtrack. In contrast to “Ohio,” “Find the Cost of Freedom” was quiet, almost elegiac: a simple, dramatic showcase for their voices and Stills' acoustic lead. Young had the A-side, with Stills' song on the flip, but for once the old Springfield wars failed to materialize. “They were on a musical mission to get this done and out,” Halverson recalled. “It was, âWe've got to get on the same page and make this right.'”

Déjà vu

. When it was done, they gathered around four microphones and recorded a B-side, Stills' “Find the Cost of Freedom,” written but rejected for the

Easy Rider

soundtrack. In contrast to “Ohio,” “Find the Cost of Freedom” was quiet, almost elegiac: a simple, dramatic showcase for their voices and Stills' acoustic lead. Young had the A-side, with Stills' song on the flip, but for once the old Springfield wars failed to materialize. “They were on a musical mission to get this done and out,” Halverson recalled. “It was, âWe've got to get on the same page and make this right.'”

The tape was flown to Atlantic's offices in New York. For financial rather than political reasons, some at the company weren't thrilled: The label was in the midst of pressing up 45s of “Teach Your Children,” the next single from

Déjà vu

. But “Ohio” felt like the right move at the right moment.

Déjà vu

. But “Ohio” felt like the right move at the right moment.

The afternoon following the session, Crosby, Nash, and Young went to their friend Alan Pariser's house in Hollywood. Pariser, who managed bands like Delaney and Bonnie and was a well-known scene-maker, had massive speakers in his living room, and CSNY would often light up joints and listen to their new music there. Another guest at Pariser's home that evening, Albert Grossman, wound up in a heated discussion

with Crosby about politics in music. The times were so combustible that the man who had signed Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary had mixed feelings about releasing a song about Kent State. In a remarkably fast turnaround, “Ohio” was on the radio days later, even before it was in stores.

with Crosby about politics in music. The times were so combustible that the man who had signed Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary had mixed feelings about releasing a song about Kent State. In a remarkably fast turnaround, “Ohio” was on the radio days later, even before it was in stores.

In the meantime, the rehearsing continued on the Warner backlot. One day, a girl walked onto the soundstage, and Crosby grabbed her and planted a kiss on her. When Barbata asked who she was, Crosby said he didn't know; it was just someone hanging around. They were still a band and still rock stars, and their tour would finally resume in a little less than a week.

PART THREE

SUMMER INTO FALL Away, I'd Rather Sail Away

CHAPTER 9

Three days into summer, Garfunkel was no longer Art. On June 24, eighteen months after its protracted and expensive shoot began in Mexico,

Catch-22

premiered at New York's Ziegfeld Theater, just north of Times Square. In the opening credits, the name “Arthur Garfunkel” appeared onscreen. He'd first used his birth name on the back cover of

Bridge Over Troubled Water

, but its appearance here now befit both his role in a prestige film and the new, distinctive role Garfunkel saw for himself, beyond pop music and his partner.

Catch-22

premiered at New York's Ziegfeld Theater, just north of Times Square. In the opening credits, the name “Arthur Garfunkel” appeared onscreen. He'd first used his birth name on the back cover of

Bridge Over Troubled Water

, but its appearance here now befit both his role in a prestige film and the new, distinctive role Garfunkel saw for himself, beyond pop music and his partner.

It didn't take an industry insider to see that Garfunkel's warm-glow harmonies were a huge factor in making Simon's songs palatable to radio and the masses. But whether they wanted to or not, everyone around Garfunkel made him feel like the less vital and valuable half of the duo. In early 1968, Simon and Garfunkel were booked into New York's Carnegie Hall, one of the most prestigious venues they'd yet played. The demand for tickets was so great that the promoter asked Mort Lewis to add a second show. To convince his act to perform twice in one night, Lewis knew the best strategy: Call Simon first and get his consent (after telling him there wouldn't be enough freebies to give to family members if they only did one show). If he were willing, then Garfunkel would surely go along with the decisionâwhich was precisely what happened. Lewis always started with Simon.

Backstage at shows, fans would approach Garfunkel and ask, “Do you write the words or the music?” With noticeable discomfort, he'd always have to say neither. Garfunkel had taken a few cracks at songwriting

during and soon after the Tom and Jerry days, coauthoring “Hey, Schoolgirl” with Simon. Under the culturally assimilated moniker Artie Garr, he'd cut a few singles on his own during that period, including the head-in-the-clouds ballad “Dream Alone” and the peppy whitebread doo-wop “Beat Love,” the latter pushed along by a mild skiffle beat. Both were showcases for his sweet, virtuous voice and his wise-beyond-his-years views on puppy love. (“Maybe I love you and maybe I don't,” he pondered to his girlfriend in the latter.)

during and soon after the Tom and Jerry days, coauthoring “Hey, Schoolgirl” with Simon. Under the culturally assimilated moniker Artie Garr, he'd cut a few singles on his own during that period, including the head-in-the-clouds ballad “Dream Alone” and the peppy whitebread doo-wop “Beat Love,” the latter pushed along by a mild skiffle beat. Both were showcases for his sweet, virtuous voice and his wise-beyond-his-years views on puppy love. (“Maybe I love you and maybe I don't,” he pondered to his girlfriend in the latter.)

Garfunkel had had a small hand in Simon and Garfunkel compositionsâsuggesting chord changes in “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” for instanceâbut the credit, and all the publishing income, always went to Simon alone. To help smooth over any uneasy feelings, Simon began telling interviewers that Garfunkel arranged the material, although everyone knew that was merely an honorary title designed to placate Garfunkel.

Jetting down to Mexico on a plane filled with fellow

Catch-22

cast members in 1969, Garfunkel had an immediate taste of a different, more welcoming community. On the flight, Bob Balaban, then twenty-four, was so in awe of Garfunkel he didn't dare speak with him, only humming “The Sound of Silence” as a way to express his fandom. During the long, grueling hours between takes, Garfunkel and some of his costarsâAlan Arkin, Tony Perkins, and Balabanâplayed tennis on a dilapidated court near the set, and Garfunkel and Perkins would often sing together during downtime. At Simon's rental home on Blue Jay Way in Los Angeles, visitors included another

Catch-22

actor, Charles Grodin, and Jack Nicholson. One day in the summer of 1969, Garfunkel showed Grodin an envelope with Simon's handwritten lyrics to “Bridge Over Troubled Water” scrawled on the back. “Too simple,” Grodin cracked, although Garfunkel told him it would sound better with music around it. With or without Grodin's curmudgeonly jab, this alternate community was instantly intoxicating to Garfunkel; in it, he was a certified star whether or not he wrote songs.

Catch-22

cast members in 1969, Garfunkel had an immediate taste of a different, more welcoming community. On the flight, Bob Balaban, then twenty-four, was so in awe of Garfunkel he didn't dare speak with him, only humming “The Sound of Silence” as a way to express his fandom. During the long, grueling hours between takes, Garfunkel and some of his costarsâAlan Arkin, Tony Perkins, and Balabanâplayed tennis on a dilapidated court near the set, and Garfunkel and Perkins would often sing together during downtime. At Simon's rental home on Blue Jay Way in Los Angeles, visitors included another

Catch-22

actor, Charles Grodin, and Jack Nicholson. One day in the summer of 1969, Garfunkel showed Grodin an envelope with Simon's handwritten lyrics to “Bridge Over Troubled Water” scrawled on the back. “Too simple,” Grodin cracked, although Garfunkel told him it would sound better with music around it. With or without Grodin's curmudgeonly jab, this alternate community was instantly intoxicating to Garfunkel; in it, he was a certified star whether or not he wrote songs.

Even if Simon was irked by Garfunkel's participation,

Catch-22

was hard to turn down. Starting with

The Green Berets

in 1968 and extending to

Patton

, which had opened in April, pro-war films hadn't vanished, even during Vietnam; part of the country wanted to see America kick some degree of butt. But by the summer of 1970, Hollywood was eager to tap intoâand profit fromâcampus turbulence.

Getting Straight,

in theaters that May, featured Elliot Gould as a young professor navigating his way through the antiwar movement on a campus;

The Strawberry Statement,

which opened the week before

Catch-22,

found a student (played by Bruce Davison) juggling a love life and police tear-gas attacks at another fictional school. A month after

Catch-22,

Jon Voight would play a troubled student of his own in

The Revolutionary

. Each film contorted itself to appeal to ticket buyers under the age of twenty-five: “America's children lay it on the line,” read the ads for

Getting Straight,

while

The Strawberry Statement

used Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's “Ohio” and “Our House” and John Lennon's “Give Peace a Chance” on its soundtrack.

Catch-22

was hard to turn down. Starting with

The Green Berets

in 1968 and extending to

Patton

, which had opened in April, pro-war films hadn't vanished, even during Vietnam; part of the country wanted to see America kick some degree of butt. But by the summer of 1970, Hollywood was eager to tap intoâand profit fromâcampus turbulence.

Getting Straight,

in theaters that May, featured Elliot Gould as a young professor navigating his way through the antiwar movement on a campus;

The Strawberry Statement,

which opened the week before

Catch-22,

found a student (played by Bruce Davison) juggling a love life and police tear-gas attacks at another fictional school. A month after

Catch-22,

Jon Voight would play a troubled student of his own in

The Revolutionary

. Each film contorted itself to appeal to ticket buyers under the age of twenty-five: “America's children lay it on the line,” read the ads for

Getting Straight,

while

The Strawberry Statement

used Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's “Ohio” and “Our House” and John Lennon's “Give Peace a Chance” on its soundtrack.

Like

M*A*S*H,

which preceded it in the spring,

Catch-22

used a different war as a metaphor for the Vietnam conflict. It was also less sensational and felt less exploitive than any of the “hip” screw-the-establishment summer movies. But Nichols' film received a far rockier reception than

M*A*S*H

. In Heller's hands, the tale of Yossarian, an American bombardier flying missions off the coast of Italy during World War II while attempting to prove his insanity to his superiors, steadily balanced sobriety and absurdity. The film version couldn't find a unifying tone between cartoonish and somber. In

Life,

critic Richard Schickel noted that Nichols and screenwriter Buck Henry had “mislaid every bit of the humor that made the novel emotionally bearable and aesthetically memorable.” Less stinging but equally dismissive,

Newsweek

noted that “the cumulative effect is disjointedness instead of the coherence of craziness.”

M*A*S*H

purloined much of the movie's thunder, and its karma wasn't

helped when, three months before, a charred copy of

Catch-22

was found in the rubble of the West 11th Street brownstone accidentally destroyed by the Weathermen.

M*A*S*H,

which preceded it in the spring,

Catch-22

used a different war as a metaphor for the Vietnam conflict. It was also less sensational and felt less exploitive than any of the “hip” screw-the-establishment summer movies. But Nichols' film received a far rockier reception than

M*A*S*H

. In Heller's hands, the tale of Yossarian, an American bombardier flying missions off the coast of Italy during World War II while attempting to prove his insanity to his superiors, steadily balanced sobriety and absurdity. The film version couldn't find a unifying tone between cartoonish and somber. In

Life,

critic Richard Schickel noted that Nichols and screenwriter Buck Henry had “mislaid every bit of the humor that made the novel emotionally bearable and aesthetically memorable.” Less stinging but equally dismissive,

Newsweek

noted that “the cumulative effect is disjointedness instead of the coherence of craziness.”

M*A*S*H

purloined much of the movie's thunder, and its karma wasn't

helped when, three months before, a charred copy of

Catch-22

was found in the rubble of the West 11th Street brownstone accidentally destroyed by the Weathermen.

Nichols had been smart to cast Garfunkel as Nately; in Garfunkel's and Nichols' hands, Nately was a baby-faced nineteen-year-old and a logical extension of the vestal-virgin aspects of Garfunkel's voice and image. In his minor role, Garfunkel didn't have many opportunities to show his potential, although a scene in which Nately angrily confronted a cynical old Italian, played by veteran Marcel Dalio, showed promise. (“What are you talking aboutâAmerica's not going to be

destroyed

!” he barked, condemning the old man as a “shameful opportunist.”)

destroyed

!” he barked, condemning the old man as a “shameful opportunist.”)

Not everyone agreed about Garfunkel's future in film. “He has an appealing face but sounds as if he is reading his lines from a blackboard,” noted the New York

Daily News

, while the nearby

Newark Evening News

in New Jersey noted dryly that Garfunkel “has a nice face for movies but no apparent acting skills.” In what amounted to a compliment,

Variety

found Garfunkel's screen presence “winsomely effeminate.” Still, Nichols was impressed. Even before the première, he recruited Garfunkel for his next project, an adaptation of cartoonist and playwright Jules Feiffer's unproduced play

True Confessions

.

Daily News

, while the nearby

Newark Evening News

in New Jersey noted dryly that Garfunkel “has a nice face for movies but no apparent acting skills.” In what amounted to a compliment,

Variety

found Garfunkel's screen presence “winsomely effeminate.” Still, Nichols was impressed. Even before the première, he recruited Garfunkel for his next project, an adaptation of cartoonist and playwright Jules Feiffer's unproduced play

True Confessions

.

Simon and Lewis had no choice but to go along; at least this time, there were no album sessions scheduled for the fall, when the next film would begin shooting. “Paul felt, âWhy's he doing that?'” Lewis recalled. “âWe have this successful thing we're doing.'” For those who worked with them, it wasn't hard to grasp Garfunkel's rationale. Over many years, he'd had to take a backseat to Simon in the music world, and he was still stung by Simon's early attempt to fly solo during the Tom and Jerry period. With movie roles, Garfunkel could achieve parity in their relationship. If all went well, he stood the chance of becoming an even bigger nameâa movie star name. Simon may have been the primary creative force in the duo, the writer of the songs on which they harmonized

so tenderly, but Garfunkel would be a man of all media. If it bothered his partner of most of the previous fifteen years, so be it.

so tenderly, but Garfunkel would be a man of all media. If it bothered his partner of most of the previous fifteen years, so be it.

Other books

My Boyfriend is a Monster by Coates, J.H.

Dare to Love (Young Adult Romance) by Naramore, Rosemarie

Pursuit of a Parcel by Patricia Wentworth

A Woman Scorned by Liz Carlyle

Naked Truth by Delphine Dryden

Dark Demands 01: Taken for His Captive by Nell Henderson

Ciudad piloto by Jesús Mate

Death Takes a Gander by Goff, Christine

Ex-Factor (Diamond Girls) by Dane, Elisa