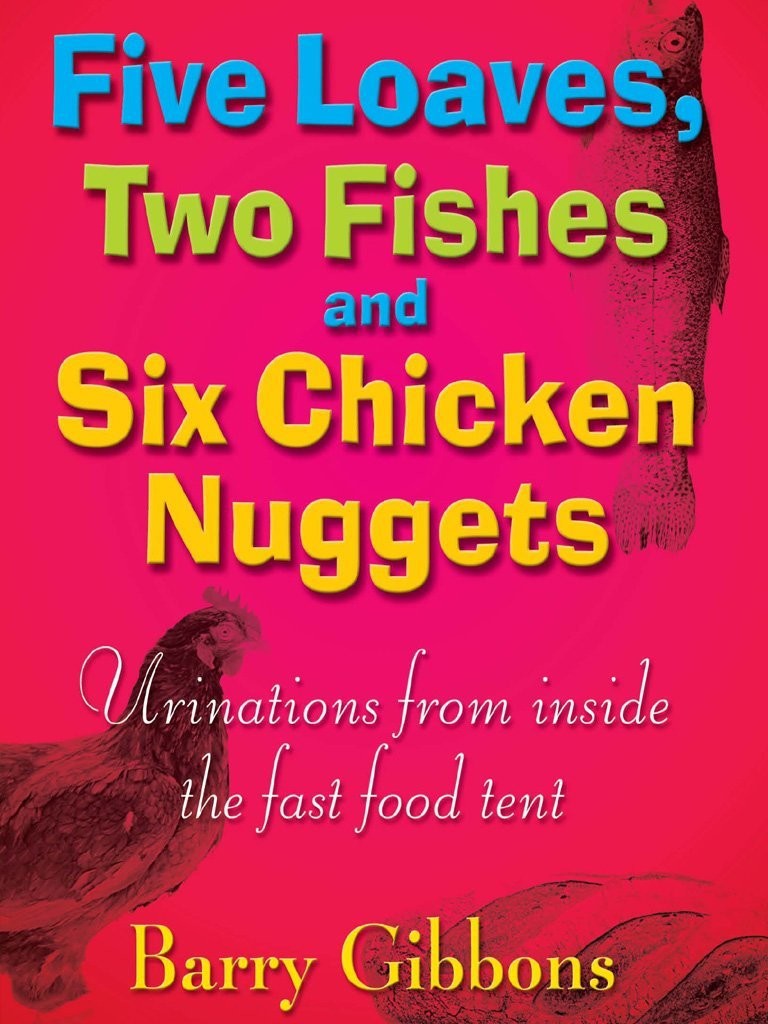

Five Loaves, Two Fishes and Six Chicken Nuggets: Urinations From Inside the Fast Food Tent

Authors: Barry Gibbons

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General

Contents

Five loaves, two fishes and six chicken nuggets

8. Even the big cheese must budget

10. No wonder we are living longer

12. ‘I say, would you mind … ?’

13. First, finish your chicken

18. Go on, surprise me: make my day

20. And now for something completely different

21. Mediocre, sad and cheating: the ascent of man

23. Trattorias, osterias and big quick-serves

24. What I know; what I don’t know

33. McD’s and the perfect storm

34. The enemy is inside the gates

39. Feeding people? What’s the problem?

40. Next time you post a letter …

54. India on 10,000 calories a day

Five loaves, two fishes and six chicken nuggets

Urinations from inside the fast food tent

Barry Gibbons

Introduction

M

y interest in the combination of the words ‘food’ and ‘quick’ started at an early age. And I mean a very early age – probably within a few seconds of me taking my first breath. Let me explain.

I arrived on this planet dangerously ahead of schedule – many weeks premature. I’ve never seen any documentary evidence to confirm it, but apparently I weighed in at less than four pounds. Such was my condition, and the state of medical science at the time (1946), that I was not expected to see the night through. My response was not untypical of many I have given since when faced with one of life’s minefields, namely to utter a rude word and then find something to eat. I slurped heartily during the night and, come the dawn, set off on my life’s goal of putting on another 185 pounds.

My journey has, at times, represented a sort of demented hopscotch. As a student, I had a variety of jobs to help with the funding. I worked in a pie factory, and saw things put in a pastry case that Saddam Hussein would have been reluctant to drop on the Kurds. I drove an ice-cream van, through Liverpool in the industrial north of England, with the external loudspeaker chime set at 78 rpm when it should have been 45 rpm. The locals reminisced that they had neither seen nor heard anything like it since the Keystone Kops. Later, I headed Bernie Inns, the UK’s famous steakhouse chain. In one memorable evening, between 6.00 p.m. and 10.45 p.m., I personally supervised one restaurant serving 385 meals on 100 covers. Most customers enjoyed their meal, but some complained of dizziness.

This particular pilgrim’s progress peaked when I was handed responsibility for every Burger King on planet earth. We were based on the coast in Florida, at the

exact

point where some god had decreed that Hurricane Andrew would come ashore in 1992, just three years after my arrival. I was an Englishman running an American icon brand – and you can imagine how the American franchisees took to me. To this day, some of them celebrate my memory by sacrificing a goat on my birthday.

I decided to quit ‘big business’ before my fiftieth birthday. It was my choice, and one not wholly celebrated by my bank manager. I set off on a very different journey, splashing about in life’s shallow end. My only goal was to forget one person every day, so that when Alzheimer’s eventually arrived I would be ahead of the game.

Of course, it didn’t work out like that. I ended up giving speeches all over the world to vaguely interested business audiences and writing books that consistently missed the best-seller lists. I invested in businesses that had less going for them than the pie inserts of the previous page.

And then, somehow or other, amidst all that, I agreed to write some essays for a US magazine that is the clearing house for all things to do with the quick-serve restaurant business. This is an industry with which I was obviously familiar, which popularly goes under the name of ‘fast food’ and/or ‘food service’. I repeated my successful formula from previous years, which was to take a brief, study it diligently – and then ignore it all together. Quick-serve food is not just about five global US brands and not just about today. In one form or another, it is worldwide and has been throughout history. If you step back from it, and look at it through a different pair of eyeglasses, you can conjure up some weird thoughts. Did the model for modern franchising (so loved in the quick-serve business) first see the light of day in the way Victorian England handed out chunks of India to loosely agreeing and agreeable princes? When, in history, was the first sandwich made – and of what and by whom? Can it be true that the world quick-serve’s epicentre,

Place Jemaa el Fna

, in Marrakech, assembles itself from nothing, and then de-assembles itself again, all within the space of a few hours every evening? Is it possible to drive the few miles from the ruins of Pompeii to Sorrento, sit in the town square, and eat a quick-serve that is essentially the same as was being eaten by some poor guy when he was rudely interrupted by his own sudden death?

I am a man of iron discipline. My essays (nearly) always contained the words ‘quick’ and ‘serve’, but they increasingly reflected that particular business in the context of my fascination with history, geography and the issues facing a broader business church. And then something else happened.

The early 2000s saw a geometric increase in the number of people taking pot shots at the food industry in general, and quick-serves in particular. Some of them have been deserved because, on occasion, the industry seems to have a monopoly of daft people, ideas and practices. But it is also, in its widest sense, an enormous positive for the planet. It employs, creates wealth for, and feeds millions (and probably billions if you push the definition a bit) every day. It is hard to think of what the realistic alternative(s) might be.

So, while I was theorising about pre-neolithic flatbreads and business models from Crete, I also sought to provide some balance for the debate. Some famous military leader, whose name escapes me, was once asked why he sought a rather dubious party as an ally. His reply was succinct: ‘I’d rather have him in my tent pissing out, than outside my tent pissing in.’ These essays are posted from inside the industry tent.

It all resulted in approaching sixty essays, all of which have been rewritten for this book. They have been updated and (in some cases) embarrassingly rewritten as the passage of time occasionally threw doubts on my claim to have a monopoly of forecasting wisdom.

Welcome to this collection of

urinations from inside the fast-food tent

.

Barry Gibbons

Bedford, England, 2006

1. In the beginning

T

he idea came at a rather inconvenient time, as most of mine do. Nowadays, I split my time between my UK home, which is near London, and Miami (which is near the United States), and my life is spent advising heads of state, Presidential candidates, and Chinese gangs. I was having a quiet one-on-one with Queen Elizabeth in a KFC in London – she likes food served in a cardboard bucket – and we were discussing my plan to grow Prince Charles’s hair over the tops of his ears to stop him looking like a demented elephant calf, when her cellular phone rang out. It was for me. She was not amused.

It was the editor of a refined US journal, suggesting I write a series of essays on the quick-serve food business – ‘fast food’ to the uninitiated. As this is a subject that has fascinated me for nearly thirty years, I accepted on the spot. I was so happy I knocked over Her Majesty’s bucket.

Serving food for a living is now one of the toughest challenges there is. Success in business is about achieving real distinction and generating widespread awareness in increasingly cluttered and competitive markets. Using that definition, quick-serve restaurants can make the case to be in the most cluttered and competitive market on the planet.

The good news is that the industry suffers less competition from the World Wide Web than most businesses involving a product or service sold to a customer. It’s easy to sell a CD or book on the web, but tough to deliver a turkey sandwich in three minutes. The bad news is that that’s really the end of the good news, because the industry goes about its difficult task with an almost Neanderthal mindset.

This is an industry that loves statistics – usually the wrong ones. During the five years of the First World War, about ten million people died untimely, awful deaths as a direct result of the conflict. About a million books have been written on the subject, and I bow to no one in the depth of my horror at the thought of it all. Immediately after the war, however, more than twice that many people died untimely and awful deaths from a new form of influenza – Spanish or Septic flu. Not as emotive, but in terms of the impact on the human race, profoundly more important. Even so, you’ll have a job finding a book on it. In the same way, the foodservice industry loves statistics on ‘cost of product’ and ‘same-store sales revenues’. I have never put either of those in the bank. The only thing that matters is sustainable cash flow. But that’s like Spanish flu – you never hear about it.