Read Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation Online

Authors: Elissa Stein,Susan Kim

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #History, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Personal Health, #Social History, #Women in History, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Basic Science, #Physiology

Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation (8 page)

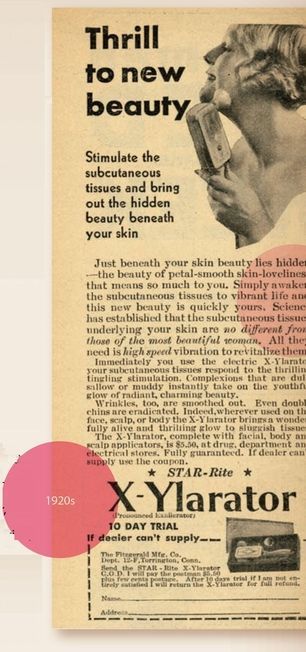

What a boon! The vibrator quickly became a staple in doctors’ offices, and as treatments sped up, revenue streams (ahem) shot through the roof. According to Rachel Maines in her 2001 book, The Technology of Orgasm, the eventual variety of vibrators offered in the late nineteenth century rivaled and possibly surpassed the inventory of today, even in the best-stocked sex shop: “musical vibrators, counterweighted vibrators, vibratory forks, undulating wire coils called vibratiles, vibrators that hung from the ceiling, vibrators attached to tables, floor models on rollers and portable devices … powered by electric current, battery, foot pedal, water turbine, gas engine or air pressure … at speeds ranging from 1,000 to 7,000 pulses per minute.”

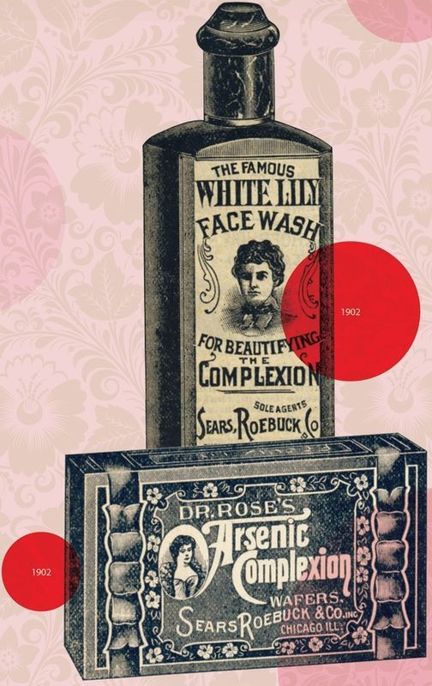

And with the first public utilities bringing electricity directly into the home, special vibrators were quickly developed and sold through catalogs for use in the privacy of one’s own boudoir. The “electrotherapeutic industry” became wildly successful; vibrator ads began to jockey for dominance, discreetly, against ads for hair pomade, ribbons, and lavender soap in women’s magazines like Needle Craft, Modern Women, and Women’s Home Companion. One brand, the Moon Massage Vibrator, was advertised as “the little home doctor.” Even the supremely square Sears Roebuck catalog carried, in a 1918 ad called “Aids That Every Woman Appreciates,” a blurb for a portable vibrator that came with ominous-sounding attachments, like the “buffer” and “grinder.” The vibrator was electrified nine years before the vacuum cleaner and beat electric frying pans by almost ten.

To say that there has always been an obvious need for genuine, clitoral-based sexual gratification for women—provided either by doctor, midwife, or mechanical/electrical device—seems to be quite the understatement. And yet, what’s so odd about the need for female pleasure? Certainly, men have been availing themselves of the services of prostitutes from the moment those early hominids stood upright and certain women could say, “Hey there, sailor”; it’s not called the world’s oldest profession for nothing.

But what intrigues us is the fact that women’s sexuality—both its repression and expression—has been perceived in such doggedly detached, clinical, and deliberately nonerotic terms, for thousands of years, whether consciously or unconsciously, as both the source of and solution to a concocted medical problem. Men have admittedly come up with some wacky notions before, but to us, this one really takes the cake.

So how did this all come about? And why?

And what is hysteria, anyway?

Hysteria was perhaps the greatest false diagnosis ever made in the history of Western medicine: a phony medical condition dating back to even before ancient Greece and only bowing out as an official disease when the American Psychiatric Association finally dropped the term in 1952. It included such an extraordinary range of symptoms, it’s hard to imagine anyone reaching a diagnosis with a straight face. A partial list includes: nervousness, insomnia, faintness, chills, fluid retention, heaviness in the abdomen, depression, headache, upset stomach, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, irritability, unexplained laughter or crying, anxiety, a choking sensation, muscle spasms, convulsions, fatigue, loss of appetite, cold hands, cold feet, loss of sexual interest, heaving of the chest, a sudden throwing back of the head and body, “the tendency to cause trouble,” and on, and on, and on, ad infinitum. Symptoms allegedly ran one Victorian doctor seventy-five pages in an unfinished list. And as one scans the seemingly bottomless inventory, one cannot help but notice the distinctly sexual nature of many of the symptoms: anxiety, sleeplessness, irritability, nervousness, erotic fantasy, sensations of heaviness in the abdomen, lower pelvic swelling, vaginal lubrication.

From the very beginning, hysteria was believed to be caused by the uterus and was even named after that pear-shaped pelvic pouch. And what we find especially telling is that the uterus, funnily enough, is the only female organ for which there is no male counterpart.

Think about it: men have breasts, the ovaries and testicles are both gonads, and one can go on and on throughout both male and female bodies, finding reasonable equivalents. But a male uterus? Nothing even comes close, unless one is generous and counts a beer belly. And thus due to its inherently and exclusively female essence, not to mention its seemingly magical ability to make babies, the innocent womb has since time immemorial been both whipping boy and Rorschach inkblot to men, the object of far too much masculine speculation and fantasy, as well as the brunt of their frequently cruel medical attentions.

In an ancient Egyptian papyrus from around 1900 B.C. (one of the earliest records in medical history, we’d like to point out), aberrant behavior in women was already being commented on and the theory put forth that a wandering uterus was the root of their problems. As a result, Egyptian doctors routinely fed noxious substances to their female patients, hoping to drive the uterus away from the lungs and throat. Alternately, they placed sweet-smelling substances on the vulva, trying to coax it back into place. The ancient Greeks (who otherwise made huge strides in medical knowledge and conceivably should have known better) agreed wholeheartedly that the uterus was in fact rampaging through the body, in a frantic search for babies.

And so what was the cure for a cranky womb? The Greeks decided that the only way to both cheer it up and promptly relieve the symptoms of hysteria was marriage—or to put it more bluntly, lots and lots of sex. Marital relations would satisfy the uterus’s need for moisture (from semen, if we need to draw you a picture), as well as give it those babies it was seeking so desperately.

Prescribing marital sex for hysteria was popular until the Middle Ages, when fundamentalist religious fervor replaced rational thought. Not that using sex to placate an angry organ was exactly what one would normally call rational; yet it was better than the Catholic Church’s position on hysteria, which was that it was caused by possession by evil spirits.

During the Middle Ages, which lasted from the fifth century to the sixteenth, things previously taken for granted, like science, medicine, democracy, and philosophy, were flung out the window like so much offal as the Church tightened its already mighty grip on society itself. Any undiagnosable illnesses or instances of bizarre behavior were now diagnosed, conveniently if not constructively, as having been brought on by the devil himself. So instead of being summarily married off, women unfortunate enough to merit the diagnosis of hysteria were instead tried in Church courts and often prosecuted as witches.

To be honest, the Church during the Middle Ages seemed to be particularly down on all women, and not just hysterical ones. Midwives in particular seemed to merit an especially hairy eyeball, what with all that spooky healing knowledge, those eerily effective herbal remedies, and that life-saving familiarity with childbirth, contraception, and other gynecological matters. Clearly in league with You-Know-Who, they too were frequently prosecuted by the Church as witches.

Fortunately, there were still intrepid individuals who bucked the oppressive religious trend and furtively continued to explore science. Not swallowing the idea that demonic possession was responsible for any kind of pathology, these men began once again to question how the body actually worked, theorizing about its many systems.

It’s important to keep in mind that throughout virtually all of history, even in supposedly enlightened times, a woman’s body and mind were considered significantly inferior to and less evolved than a man’s: designed for bearing children, but still weaker, feebler, and more poorly made. An 1848 obstetrics text wrote that “she (woman) has a head almost too small for intellect, but just big enough for love.” What’s more, her body was a total mystery, as well, both intimidating and scary: periodically bleeding, producing children, and so on. Until the 1700s, female genitalia was considered to be all lumped together, without distinct vocabulary to distinguish its different parts.

In the nineteenth century, however, Jean-Martin Charcot, one of the earliest modern neurologists, put forth the first scientific argument against the centuries-old wandering-womb theory and suggested that hysteria was instead a brain-based phenomenon, with physical manifestations. Two of his students, Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud, went on to posit that hysteria was psychological in origin, with symptoms arising from the subconscious. In other words, unresolved conflict manifested itself symbolically as physical symptoms. This theory was a huge step forward in many ways, as well as a disturbing step back.

Freud himself, who once wrote that “women oppose change, receive passively, and add nothing of their own,” clearly had issues of his own when it came to unresolved conflict, especially with regard to women. He freely projected his own sexual insecurities while attributing possible causes of hysteria: he suggested penis envy, the Oedipal complex, and castration anxiety, all of which indicate, to us at least, a certain infantile phallocentrism. But he ultimately came closest to the mark when he concluded that hysteria represented unresolved sexual conflict. To his mind, many women, if not most, were sexually frigid.

These weren’t quite the fightin’ words then that they are now. The Victorian era was almost cartoonishly repressed and repressive, especially for middle- and upper-class women, and it was the rare female who could actually get jiggy in the bedroom. The ideal woman of Freud’s day was passive, modest, restricted with heavy clothing, and uninterested in sex. In fact, hygiene manuals actually warned against “spasmodic convulsion” in the woman during sex, lest it interfere with all-important conception. With that as the wifely role model, is it any surprise that prostitution became such a boom business during the Victorian era?

Perhaps not coincidentally, hysteria experienced its heyday in the mid- to late nineteenth century, sweeping through the middle and upper-middle echelons of British and American society like a forest fire run amok, afflicting an untold number of women. In 1871, women’s rights educator Catherine Beecher wrote despairingly of “hopeless invalidism,” “the mysterious epidemic,” and “a terrible decay of female health all over the land, which was increasing in a most alarming ratio.” Wealthy women took to the supine position in record numbers, and as a direct result, a morbid sickliness became le dernier cri, the latest romanticized aesthetic ideal. Artists and poets lovingly described pasty, tremblingly frail women languishing on their chaises, smelling salts in hand. Ghastly white pallor was also deemed a fashion “do,” as it bespoke the refinement of one who didn’t labor in the fields (a robust tan being a definite fashion “don’t”). To achieve this rarefied, Bozo the Clown look, women routinely painted their skin with white lead, zinc oxide, mercury, lead, or nitrate of silver … which led to other, far more serious medical problems.

Speaking of fashion, it was the hellishly restrictive clothing styles of the day that also created severe health problems, many of which would have certainly contributed to a diagnosis of hysteria. As Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English noted in their 1989 book, For Her Own Good: “Corsets exerted, on the average, 21 pounds of pressure on a woman’s organs, and extremes up to 88 pounds had been measured … . Some of the results of tight lacing were shortness of breath, constipation, weakness, indigestion. Among the long-term effects were bent or broken ribs, displacement of the liver, uterine prolapse. In some cases the uterus would be gradually forced by the pressure of the corset down through the vagina.”

Another possible cause of hysteria was dietary—namely too much sugar enjoyed by middle- and upper-class women, which led not only to tooth decay, but also infections, digestive problems, and low energy. In 1898, Dr. Lyman Sperry, the author of Confidential Talks with Young Women, blamed excessive sweet eating as the undiagnosed cause of many mental and physical problems of the day.

To be fair, not everyone bought into the whole idea of hysteria; in fact, many skeptics believed women were fabricating such attacks in a Victorian manifestation of the Drama Queen just to get attention. Several pointed out that hysterics never had fits when they were alone. Plus, the mysterious ailment only seemed to affect the women who could actually afford to be terminally bedridden; you sure didn’t catch the working class falling prey to hysteria. To deal with an outburst, doctors suggested suffocating the woman until her fits stopped, or beating her with a wet towel or otherwise humiliating her in front of family and friends until she finally quit.