Fools' Gold (21 page)

Authors: Philippa Gregory

‘She means me,’ Ishraq intervened. ‘He asked her to bring me to him.’

Lady Carintha put her hands on her hips and looked at the two younger women. ‘Well, what are we to do? For I won’t share him. And we can’t all go in together and let him choose. That would be to spoil him, and besides, I don’t take gambles like that. I’m not lining up against you two little lovelies.’

‘But you like to gamble,’ Ishraq pointed out. ‘Why don’t we gamble for him?’

Lady Carintha gave a delighted laugh. ‘My dear, you are wilder than you appear. But I have no dice.’

‘We have nobles,’ Ishraq pointed out. ‘We could toss for him.’

‘How very appropriate,’ she said drily. ‘Who wins?’

‘We each toss a noble until there is an odd one out. That woman wins. She goes into the garden. She has time with Luca – whatever she does nobody ever knows – and we never speak of it,’ Ishraq ruled. ‘Do you agree?’

‘I agree,’ Isolde whispered.

‘Amen,’ Lady Carintha said blasphemously. ‘Why not?’

Ishraq took the borrowed nobles from her pocket and gave Isolde one, and took another for herself. Lady Carintha already had hers in her hand.

‘Good luck!’ Lady Carintha said, smiling. ‘One, two three!’

The three golden coins flicked into the air all together, turned and shone in the moonlight, then each woman caught her own as it fell, and slapped it on the back of her hand. They stretched out their hands each holding a hidden coin under the palm of the other hand. Slowly, one at a time, one after the other, they uncovered them.

‘Ship,’ said one, showing the engraved portrait of the king in his ship on one side of the coin.

‘Ship,’ said another, uncovering her coin.

The two of them turned to the third as she raised her fingers and showed them the shining face of her coin.

‘Rose,’ she said, and without another word, turned to the door in the high wall, turned the heavy ring of the latch, and went quietly in.

The light of the moon suddenly dimmed as a cloud crossed its broad yellow face. In the garden, Luca rose to his feet as very, very quietly, the garden gate opened and a masked figure stood underneath the arch. Luca stared, as if she were a vision, summoned up by his own whispered desire. ‘Is that you?’ he asked. ‘Is it really you?’

Silently, she stretched out her hand to him. Silently, he stepped towards her. Luca drew her into the shade of the tree, pushing the door shut behind them. Gently he put his hand around her waist and held her to him, she turned up her face to him in the darkness, and he kissed her on the lips.

She made no protest as he led her under the roof of the portico and they sat on the bench in the alcove. Willingly, she sat on his knee and wound her arms around his neck, rested her head on his shoulder and inhaled the warm male scent. Luca drew her closer, heard his own heart beating faster as he unlaced the back of her gown and found her skin, as smooth as a peach beneath the dark coloured silk. Only once did she resist him, when he went to untie her mask and put back the hood of her robe, and then she captured his hand to prevent him from unmasking her, and put it to her lips, which made him kiss her again, on her mouth, on her throat, on the warm hollow of her collar bones until he had spent the whole night in kissing her, the whole night in loving her, in learning every curve of her body, until the first light of dawn made the canal as dark as pewter, and the garden as pale as silver, and the birds started to sing and she rose up, gathered her shadowy cloak around her, pulled the hood to hide her hair, shading her face when he would have kept her and kissed her again, stepped silently out of the garden gate and disappeared into the Venice dawn.

Next morning the five of them met for a late breakfast. Luca jumped to his feet to pull out a chair for Isolde and she thanked him with a small smile. He passed her the warm rolls, straight from the kitchen, and she took the bread basket with quiet thanks. Luca was like a man who had been staring at the sun, utterly dazzled, hardly knowing himself. Isolde was very quiet.

Freize raised his eyebrows to Ishraq as if to ask her what was going on, but serenely she ignored him, her eyes turned down to her plate, smiling as if she had a secret joy. Finally, he could contain himself no longer. ‘So how was your party, last night?’ he asked cheerfully. ‘Did it go merrily?’

Isolde answered smoothly. ‘We went upstairs to meet Lady Carintha, and we borrowed some gold nobles from her to gamble. I suppose we’ll have to return them. The women were a vain, vapid lot. They spoke of nothing but clothes and lovers. Brother Peter is quite right, it is a city empty of anything but sin. We came home about ten o’clock and strolled about for a few minutes and then went to bed.’

Luca was staring at his plate, but he looked up just once, as she spoke. He stared at her, as if he could not understand the simple words. She did not glance at him, as he pushed back his chair from the table and went to the window.

‘So what are we to do today?’ Freize asked.

‘As soon as Luca and Ishraq have completed work on the manuscript and returned it to the alchemist and his daughter then we must report them to the authorities,’ Brother Peter said firmly. ‘If you could return it today, we could report them today. I would prefer that. I don’t want them coming to our house again. They are criminals and perhaps dabbling in dark arts. They should not visit us. We should not be known as their friends.’

‘How do we report them?’ Ishraq asked. ‘Who do we tell?’

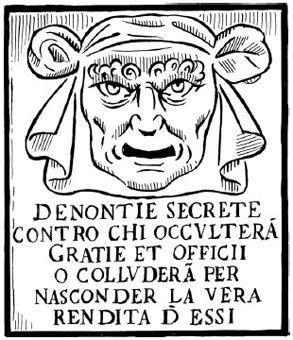

‘We’ll denounce them,’ Brother Peter said. ‘All around the city and in the walls of the palace of the Doge there are big stone letter boxes with gaping mouths. They call them the

Bocca di Leone,

the mouth of the lion. Venice is the city of the lion: that’s the symbol of the apostle, St Mark. Anyone can write anything about anybody and post it into the

Bocca.

All Luca has to do is to name the pair of them as alchemists, Freize and I will sign as witnesses, and they will be arrested as soon as the Council reads the letter.’

Isolde blinked at the Venetian way of justice. ‘When will the Council read the letters of denunciation?’

‘The very same day,’ Brother Peter said grimly. ‘The boxes are constantly checked and the Council of Ten reads all the letters at once. This is the safest city in Christendom. Every man denounces his neighbour at the first sign of ill-doing.’

‘But what will happen to Drago and Jacinta?’ Freize asked. ‘When this council reads your accusation?’

Brother Peter looked uncomfortable. ‘They will be arrested, I suppose,’ he said. ‘Then tried, then punished. That’s up to the authorities. They’ll get a fair trial. This is a city of lawyers.’

‘But surely alchemy isn’t illegal?’ Isolde objected. ‘There are dozens of alchemists working in the university here, and even more at Padua. People admire their scholarship, how else will anything ever be understood?’

‘Alchemy isn’t illegal if you have a licence, but some applications of alchemy are illegal. And forgery is a most serious crime, of course,’ Brother Peter explained. ‘Anyone making gold English noble coins anywhere outside an official mint is a forger, and that is a crime, that is very heavily punished.’

‘Punished how?’ Freize interrupted, thinking of the pretty girl and her bright smile.

‘The Council will hear the evidence, make a judgement and then decide the punishment,’ Brother Peter said awkwardly. ‘But for coining, it would usually be death. They take their currency very seriously, here.’

Freize was shocked. ‘But the lass – the bonny lass—’

‘I don’t think the Doge of Venice makes much exception for how pretty a criminal is,’ Brother Peter said heavily. ‘Since the city is filled with beautiful sinners, I doubt that it makes much difference to him.’

Freize glanced at Luca, who was still gazing out of the window. ‘Seems too harsh,’ he said. ‘Seems wrong. I know they’re forgers, but it seems too great a punishment for the crime. I wouldn’t want to turn them in to their deaths.’

Luca, hardly listening, glanced up from his silent survey of the canal. ‘They would be aware of the punishment before they did the crime,’ he said. ‘And they will have made a fortune. Didn’t Ishraq say they had six sacks of gold on the quayside? And didn’t you see the moulds for making the gold yourself, and their furnace?’

‘I don’t say they’re innocent, I just think they shouldn’t die for it,’ Freize persisted.

Luca shook his head as if it were a puzzle too great for him. ‘It’s not for us to decide,’ he ruled. ‘I just inquire. It’s my job to find signs for the end of days, and if I find sin or wrongdoing I report it to the Church if it is sin, or to the authorities if it is a crime. This, clearly, is a crime. Clearly it has to be reported. However pretty the girl. And these are Milord’s orders.’

‘They’re not just forgers,’ Freize pressed on. ‘They’re inquirers, like you. They study things. They’re scholars. They know things.’

He reached into the deep pocket of his coat and brought out a little piece of glass. ‘Look,’ he said. ‘They’re interested in light, just like you are. I stole this for you. Off Jacinta’s writing table.’

‘Stole!’ Brother Peter exclaimed.

‘Stole from a forger! Stole from a thief!’ Freize retorted. ‘So hardly stealing at all. But isn’t it the sort of thing you’re interested in? And she’s studying it too. She’s an inquirer like you, she’s not a common criminal. She might know things you want to know. She shouldn’t be arrested.’

He put it on the table and uncurled his fingers so slowly, that they could see the little miracle that he had brought from the forger’s house. It was a long, triangular-shaped piece of perfectly clear glass. And as Freize put it on the breakfast table between Isolde and Ishraq, the sun, shining through the slats of the shutters, struck its sharp spine and surrounded the piece of glass in a perfect fan of rainbow colours, springing from the point of the glass.

Luca sighed in intense pleasure, like a man seeing a miracle. ‘The glass turns the sunlight into a rainbow,’ he said. ‘Just like in the mausoleum. How does it do that?’

He reached into his pocket and brought out the chipped piece of glass from Ravenna. Both of them, side by side, spread a fan of rainbow colours over the table. Ishraq reached forward and put her finger into the rainbow light. At once they could see the shadow of her finger, and the remnants of rainbow on her hand. She turned her hand over so that the colours spread from her fingers to her palm. ‘I am holding a rainbow,’ she said, her voice hushed with wonder. ‘I am holding a rainbow.’

‘How can such a thing be?’ Luca demanded, coming close and taking the glass piece to the window, looking through it to see it was quite clear. ‘How can a piece of glass turn sunshine into a rainbow arc? And why do the colours bend from the glass? Why don’t they come out straight?’

‘Why don’t you ask them?’ Freize suggested.

‘What?’

‘Why don’t you ask them to show you their work, or tell you about rainbows?’ Freize repeated. ‘He’s known as an alchemist, he’ll be used to people coming to him with questions. Why don’t you ask him about the rainbow in the tomb of Galla Placidia? See what we can learn from them before we report them? Surely we should know more about them. Surely you want to know why she has a glass that makes a rainbow?’