Fordlandia (5 page)

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

Manaus is famous for its hulking Amazonas Theater, an opera house built of Italian marble and surrounded by roads made of rubber so the carriage clatter of late arrivals wouldn’t interrupt the voices of Europe’s best tenors and sopranos. Finished in 1896, it reportedly cost more than two million dollars to construct. Money flowed freely during the boom, and Manaus’s better classes imported whatever they could at whatever price. American explorers found that they could sell their used khakis for five times what they paid for them at home, once they grew tired of parading around the city in their jungle gear.

*

With more movie theaters than Rio and more playhouses than Lisbon, Manaus was the second city in all of Brazil to be lighted by electricity, and visitors who came upon it from the river at night during the last years of the nineteenth century marveled at its brilliance in the midst of darkness, “pulsating with the feverish throb of the world.” But not just light made Manaus and Belém, also electrified early, modern. Their many dark spaces provided venues for quintessentially urban pleasures. Roger Casement, Britain’s consul in Rio, who later would become famous for his anti-imperialist and antislavery activities, wrote in his diary in 1911 about cruising Manaus’s docks, picking up young men for anonymous sex. Belém, for its part, wrote a

Los Angeles Times

correspondent in 1899, had an “amount of vice” that would shock the “reformers of New York,” most of which could be found in its many cafes and cabarets, as well as its best brothel, the High Life Hotel, which is “devoted to the life of the lowest order” and which Brazilians pronounced, according to the journalist, as “Higgy Liffey.”

12

A contemporary view of the opera house in Manaus, the tropical Paris

.

From start to finish, the production of rubber that made such affluence possible represented an extreme contrast to the industrial method pioneered by Henry Ford in Michigan.

Hevea brasiliensis

can grow as high as a hundred feet, standing straight with an average girth, at breast height, of about one meter in diameter. It’s an old species, and during its millennia-long history there likewise evolved an army of insects and fungi that feed off its leaves, as well as mammals that eat its seeds. In its native habitats of Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador, it best grows wild, just a few trees per acre, far enough apart to keep bugs and blight at bay; would-be planters soon learned that the cultivation of large numbers of rubber trees in close proximity greatly increased the population of rubber’s predators. The extraction and processing of latex, therefore, was based not on developing large plantations or investing in infrastructure but rather on a cumbersome and often violent system of peonage, in which tappers were compelled to spread out through the jungle and collect sap.

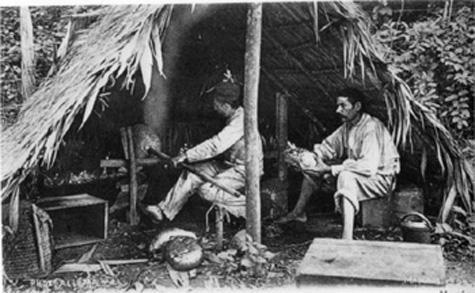

Tappers, known as

seringueiros

, lived scattered along the river, sometimes with their families but often alone, with their huts located at the head of one or two looped rubber trails that ran a few miles, connecting between a hundred and two hundred trees. In the morning, starting before sunrise, when the latex flowed freest through the thin vessels that run up the tree’s bark, the tapper would make his first round, slashing each

Hevea

with diagonal cuts and then placing tin cans or cups to catch the falling sap. After lunch, and a nap to escape the worst of the heat, the

seringueiro

made a second round to collect the latex. Back at his hut, he smoked it on a spit over an earthenware oven fired by dampened palm nuts, which produced a toxic smoke that took its toll on tapper lungs, until it formed a black ball of rubber, weighing between seventy and ninety pounds. He then brought the ball to a trading post, handing it over to a merchant either as rent for the trails or to pay off goods purchased on credit. The rubber then made its way downriver to Belém’s receivers and export houses. The excruciatingly unhurried drip, drip, drip of the sap into a battered cup, latched onto the tree with a piece of rope or leather, was about as far removed from the synchronized speed of Henry Ford’s assembly line as one could imagine. Back in Michigan, Ford was obsessed with rooting out “slack” from not just the workday but the work year—trying to find ways to combine agricultural and industrial seasonal labor that maximized the efficiency of both. But along the Amazon,

seringueiros

often spent the “grey and sad” months of the rainy season, when latex ran too slow to tap, “in his hammock without any profitable occupation,” accumulating more debt that they would never work off. Their thatched huts were often perched on poles, and as the water rose around them they passed the rainy days in isolation, as one traveler described, alone with “dogs, fowls, and a host of insects, all unable to move far owing to the water that surrounds them.”

13

Two tappers smoking latex under a thatched lean-to

.

It was a system that produced enormous riches when Brazil had a monopoly on the world’s rubber trade and therefore largely set the global market price. But the wealth it created was fleeting and unsustainable. The tapping system itself could quickly deplete man and tree. As the seasons passed, cuts on the bark would scab over to be bled again, successively yielding less and less latex. With care,

Hevea

can produce for up to three decades, starting in its fifth or sixth year of growth, but under pressure to deliver more latex,

seringueiros

cut too often, too deep, causing stunted growth and early exhaustion. And profit was generated by what was essentially an elaborate pyramid scheme: at the apex were foreign commercial and financial houses; in the middle stood Brazilian merchants, traders, and a few exporters; and the whole thing rested on the backs of indebted tappers, who, as one critic put it, received goods on credit charged at fifty but in reality worth ten, in exchange for latex that the local merchant assessed at ten but that was actually worth fifty. As another writer noted, the “potentates of the forest have no credit beyond that on their books—against peons who never pay (unless with their lives).” Euclides da Cunha, one of the Amazon’s great chroniclers, described the trade as the “most criminal employment organization ever spawned by unbridled selfishness.”

14

The first generation of early-nineteenth-century-boom rubber tappers came from the Amazon’s native population. Things were bad for many indigenous communities prior to the rubber trade; slave raiding had already devastated many groups. “Every manner of persuasion,” one anthropologist observed, “from torture to degeneration by cachaça”—a cheap rum distilled from sugar cane juice—was used to make natives collect wild jungle products. Prior to the expansion of the latex economy, these included nuts, feathers, snake skins, dyes, fibers, pelts, timber, spices, fruit, and medicinal herbs and barks, most notably from the cinchona tree, found in the higher reaches of the upper Amazon, which produced the antimalarial alkaloid quinine, indispensable in hastening the spread of European colonialism in Asia and Africa.

15

But the rubber trade was by far more extensive, and thus more disruptive, than anything that had come before it, organizing under its regime the whole of the Amazon wherever

Hevea

was found. The Apiaca, for instance, were just one of many groups practically wiped out as a distinct tribal society, their men pressed into service either as tappers or to paddle or pole trading boats, and their women as servants or concubines. After native sources of labor were exhausted, migrants, mostly from Brazil’s drought-prone northeast, made up subsequent generations of tappers. They arrived at Manaus and Belém by the boatful, withered, sunken-faced, and already bonded to pay for their transport. Between 1800 and 1900, the lower Amazon’s population increased tenfold, with desperately poor, eternally indebted families living in small, isolated clusters of huts along the river’s many waterways or in the sprawling shantytowns that spread out behind Manaus and Belém’s Belle Époque façade.

16

But by 1925, when Ford and Firestone were thinking of getting into the rubber business, this boom had long turned to bust, largely because of the actions of another Henry, who arrived in the Amazon over half a century earlier to commit what observers today call “bio-piracy,” which would eventually unravel Brazil’s latex monopoly.

Henry Wickham was a prime example of the kind of imperial rogue chronicled by Rudyard Kipling. Only Wickham didn’t travel east to make a name for himself in Britain’s formal colonies; instead he went west to Latin America, where London in the late nineteenth century was extending its commercial and financial reach. He landed first in Nicaragua, where he tried to turn a profit exporting colorful bird plumage back to his mother’s London millinery shop, located on a small street just off what is now Piccadilly Circus. He was a bad shot, though, and soon decided to better his luck in Brazil.

17

In 1871, Wickham and his wife settled in Santarém, where the Tapajós River flows into the Amazon. Attempting to establish himself as a rubber expert, he quickly fell into destitution, surviving only thanks to the kindness of a community of U.S. Confederate exiles who, moved by, as one of the Southern expatriates put it, Wickham’s “aristocratic appearance” and “lonesome, melancholy aspect,” took the couple in. A failure at most everything in life, Wickham enjoyed one reported success, the illegal spiriting of seventy thousand Amazonian seeds, gathered from a site not far from where Fordlandia would be founded, out of Brazil in 1876. These he turned over to London’s Royal Botanic Gardens, where they were nurtured into the seedlings used to develop Asia’s latex competition. Actually, Wickham’s real success was in gaining fame for stealing the seeds, for historians of rubber have subsequently questioned key aspects of his derring-do story. Whatever the case, Queen Victoria knighted Wickham, securing his place in history as a British imperial hero and a Brazilian imperialist villain, and the Amazon began its long descent into economic stupor.

18

The seeds Wickham collected and shipped to London provided the genetic stock of all subsequent rubber plantations in the British, French, and Dutch colonies.

Hevea

was able to grow closer together in Asia, and later Africa, because the insects and fungi that feed off rubber didn’t exist in that part of the world. And when the trees began to run sufficient amounts of cheap latex to meet the world’s demand, Brazil’s rubber pyramid came toppling down. No matter how exploited the Amazonian tapper, the price of producing rubber in large estates was considerably lower than what it cost to extract it from wild groves. Asian plantations were close to major ports, which cut down on transportation expense. They used low-wage labor, often imported from China, and by the early twentieth century had selected and crossbred trees, leading to much greater sap yields. In 1912, estates in Malaya and Sumatra were producing 8,500 tons of latex, compared with the Amazon’s 38,000 tons. Two years later, Asia was exporting over 71,000 tons. Less than nine years later, that number rose to 370,000 tons. Manaus fell into fast decline, its opera house ridiculed as an emblem of folly, of the excess wealth and European strivings of rubber barons who spent their money on gold leaf, red velvet, and murals of Greek and Roman gods cavorting in the jungle, rather than on developing a sustainable economy. Belém gave way to Singapore as the world’s premier rubber exporting port, and the Amazon languished, subject of any number of plans to restore the region to glory—until Ford tried to make one happen.

19

*

Unlike Brazilians, who upon returning from the jungle usually immediately bathed, shaved, and brought a new suit of clothes, Americans, one observer noted, had the “irritating habit of stalking through the streets, and calling on the highest officials” in their “ten-gallon hats, campaign boots, and cartridge-belts” (Earl Parker Hanson,

Journey to Manaos

, New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1938, p. 292).