Read Forensic Psychology For Dummies Online

Authors: David Canter

Forensic Psychology For Dummies (85 page)

Most legitimate organisations inform the market of their products by some form of advertising, which isn’t a good idea if you want to keep the police away! Word of mouth is the only way usually open to criminal networks, and it’s slow and prone to misunderstanding.

As criminal networks grow their problems become greater. Their lines of communication become stretched, making it more difficult for communications and contacts to be controlled, as well as giving increased opportunities for mistakes. Furthermore, a larger organisation is likely to have a higher proportion of individuals on the periphery of the network, and these people may have less commitment to it.

Larger networks demand more complex organisation. Those trying to lead these networks can be pushed beyond what they can cope with. Also, lieutenants and others in less powerful positions may want more of the action and so challenge the positions of the ‘bosses’.

All these above processes create difficulty in maintaining commitment to the illegal organisation, especially if it can’t deliver direct financial benefits. Therefore, a strong tendency exists for criminal groups to keep people involved through violence and coercion.

These challenges are the key to how the authorities can destroy or damage criminal networks.

One of the consequences of the difficulty in maintaining an illegal enterprise is that such criminals are rarely formed into neat organisational hierarchies, such as the police, the army or a major corporation. They’re more likely to be a loose network of contacts that constantly changes. In fact, even the Mafia in its heyday consisted of many different ‘families’ that were constantly in competition with each other, with defections from one group to another and no one able to trust anyone.

Understanding the reality of criminal networks helps to give pointers on how they can be undermined, which I describe in the next section.

Nobbling the leader

You may think that taking out the boss is the obvious way to undermine a criminal network. But organisational psychology analysis of these networks indicates this may not always be as effective as you might think.

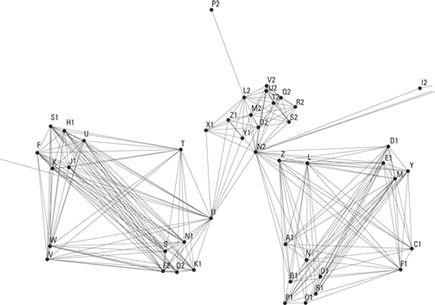

The network in Figure 8-1 illustrates why the popular idea that a criminal network can be destroyed by taking out ‘Mr Big’ may be a delusion. Many illegal networks, whether they be dealing in drugs or trafficking human beings, handling stolen goods or setting up fraudulent banking schemes, are constantly changing in a complex ad hoc arrangement of individuals. Even those involved directly in such team activities as bank robberies or hit-and-run crimes aren’t likely to keep the same group for every crime. The various members of the gang change depending on contacts and circumstances.

Figure 8-1:

A network of contacts between people involved in staging car accidents to fraudulently claim insurance.

Attacking communication links

The psychological understanding of how groups work (some of which I describe in the earlier section ‘Appreciating the difficulties facing illegal networks’) can be used to disrupt the activities of organised crime groups. One productive possibility is to gain access to their communication system and use its inherent vulnerability to identify key facts that can lead to investigative actions.

Al-Qaeda was very aware of this possibility and went to great pains to avoid electronic communication that may have given away the location of bin Laden. Nonetheless, to continue to influence his network he had to communicate with his followers. Eventually, one of them used a mobile phone carelessly, enabling the security services to locate the courier and follow him to bin Laden’s lair.

Organisational studies show that people on the edge of communication networks may have less commitment to the organisation and be more likely to become dissatisfied with it. Authorities can make use of this insight, because such people may be open to providing information, overtly or inadvertently, that can help law enforcement to undermine the criminals’ activities. In addition, criminals often keep people within the crime network through coercion, and so if members feel safe in giving evidence, that can be the key to unravelling the whole illegal organisation.

Getting to the root of the problem

Organised crime can flourish only when it has a home within a community and can’t survive without contact with clients or funders: it has to connect to and be part of a group of more or less law-abiding citizens. The psychology of these citizens therefore becomes important. Through fear or ignorance, or an inability to see things happening any other way, the community implicitly or explicitly colludes with the criminals. People in pubs may buy goods that ‘fell off the back of a truck’. Pop stars and their fans may buy illegal drugs. Famous footballers may think that forcing themselves sexually on female followers is acceptable, and the victims don’t feel able to report the rape. If the local culture accepts illegal activity such as this, it encourages the emergence of organised crime. Therefore, many aspects of organised crime prevention require tackling public awareness of what’s being supported by actions that may seem to be only minor violations of the law or not worthy of reporting – for example, making people aware of what’s involved in buying diamonds that were illegally obtained or that involved many abuses of human rights to acquire them.

Part III

Measuring the Criminal Mind

In this part . . .

Central to the day-to-day work of many forensic psychologists is the assessment of defendants and offenders. This may be, for example, to see if they are mentally fit enough to stand trial or to determine if there is a high risk of their re-offending if they are let out of prison. Deciding if a person is a psychopath is another example of such assessments. Over the years, a variety of standard procedures, often called psychological tests or instruments, have been developed to ensure the assessments are as objective as possible. To understand what forensic psychologists contribute to assessment, it is useful to understand something of how these measuring instruments are created. In this part, I describe the basics of building psychological assessments and give some examples of what they consist of and the ways in which they are used.

Chapter 9

Measuring, Testing and Assessing the Psychology of Offenders

In This Chapter

Finding out about psychological measurement

Seeing the different forms that assessment can take

Understanding the psychological areas assessed

Hearing how to evaluate psychological assessments

Hearing how to evaluate psychological assessments

As part of their job, forensic psychologists often need to form a view of someone’s psychology – usually a suspect or known offender – and guide that individual directly or advise others on how to deal with the person. Doing so, requires forensic psychologists to be able to assess that individual – for example, the person’s ability to understand the legal process well enough to participate effectively, or perhaps diagnosing particular mental or behavioural problems (with the associated implications for how the person should be dealt with and treated).

To accomplish this aim, forensic psychologists use measuring instruments (known generally as ‘psychological tests’) to assess clients. In this chapter I describe some general psychological test methods, what areas they measure and how to evaluate their effectiveness. The forms of assessment that I consider apply to the general population, but of course are relevant in forensic psychology because criminals are drawn from the general public. (For psychology assessment methods connected specifically to criminals, flip to Chapter 10.)

Introducing Psychological Measurement

People have been exploring ways of assessing psychological characteristics for over 150 years. These efforts produced a variety of psychological

measuring instruments

(assessment procedures, in other words); in essence, standardised processes that have been carefully developed and tested to ensure that they give some consistently useful information. The idea is that trained professionals can use these procedures to come up with more or less the same results. The procedures are hooked into an agreed set of ideas about what’s being measured, an agreed theory or set of defined concepts, and how the psychology of the individual is revealed through the use of the particular instruments.

When assessing clients, psychologists use psychological measuring instruments generally known as psychological tests, but more scientifically called

psychometric procedures

(that is, they deal with measurable features). The best known psychological tests are intelligence tests, which assess how a person’s intelligence compares with that of people of a similar age, resulting in an

Intelligence Quotient

(IQ). (See the later section ‘Standardising psychological tests’ for more.)

Loads of other psychological tests exist that can also be of value to legal proceedings, including assessment of various specific intellectual abilities, such as problem solving, educational attainment or particular cognitive skills such as pattern recognition. Some tests are specifically established to diagnose brain damage such as that associated with Alzheimer’s. Other tests measure various aspects of personality, such as styles of interpersonal interaction, extraversion or ways of coping with stress.

The central idea behind all psychological assessments is that the result they produce isn’t biased by the assessor’s particular way of seeing the world; in other words, the result of the assessment must be objective. This requirement is a huge task and not always fully achieved, but the processes of assessment are constructed to be as free from personal bias as possible. After all, if two psychologists assess the IQ or personality of the same individual and come up with totally different answers, no one would have faith that what they’re doing is scientific, objective and therefore useful in any way.

In this chapter, I consider general psychological tests because criminals are members of the overall population and understanding them requires knowing what sort of people they are, as it would for anyone else. Therefore, to help offenders and understand more fully their circumstances, it’s important to assess their general psychological characteristics. Intelligence level, personality and any indications of mental disorder can all be crucial for determining the nature of a person’s involvement in crime as well as how the law courts should treat them, as I discuss in more detail in Chapters 3 and 11.

Getting to Grips with Psychological Measurement Methods

Psychological tests take many different forms and aren’t restricted to ‘box-ticking’ questionnaires. The easiest way to think about the differences between different tests is in terms of what the respondents are asked to do. Are they just answering questions or being asked to complete a task? Is the psychologist listening to what they say or observing what they do? In this section, I describe just a few methods to give you more of an idea of what psychological assessment is like.

Thousands of psychological assessment possibilities exist and many major organisations are devoted to developing and selling them.

In Table 9-1, I give an overview of general psychological assessment procedures. (Procedures developed specifically for use with offenders are discussed in Chapter 10.)

Table 9-1 Summary of Personality Assessment Procedures

|

|

|

|

|

|