Forever Summer (28 page)

Authors: Nigella Lawson

325g plain flour

half a teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon baking powder

5 tablespoons caster sugar

125g unsalted butter, frozen

1 large egg, beaten

125ml single cream

1 egg white, lightly beaten

for the filling:

250ml double cream

3 large passionfruit (or 6 small)

Preheat the oven to 200°C/gas mark 6.

Sift the flour, salt and baking powder into a large bowl and add 3 tablespoons of the sugar. Grate the butter into these dry ingredients, and use your fingertips to finish crumbling the butter into the flour. All you need to do is use the coarse holes of an ordinary grater, but if you prefer just cut the butter into pea-sized pieces and work it into the flour either by hand or with the paddle attachment of a free-standing mixer.

Whisk the egg into the single cream, and pour into the flour mixture a little at a time, using a fork to mix. You may not need all of the eggy cream to make the dough come together, so go cautiously.

Turn the dough out on to a lightly floured surface, and roll lightly to a thickness of about 2cm. Using a 6.5cm round scone or biscuit cutter, dipped in flour, cut out as many rounds as you can. Work the scraps back into a dough and re-roll if necessary to form six rounds in all.

Place the shortcakes about 2.5cm apart on a baking sheet, brush the tops with the egg white, and sprinkle them with the remaining 2 tablespoons of caster sugar. (If it

helps with the rest of your cooking, or life in general, you can cover and refrigerate them now for up to 2 hours.) Bake for 10-15 minutes, until golden brown, and let them cool for a short while on a wire rack. The shortcakes should be eaten while still warm, so this stage doesn’t take that long. But don’t panic if they aren’t warm when you eat them; the one thing you don’t want to be doing is hovering nervously about the oven when you’ve got friends over.

Either before you sit down to eat or as you go to assemble the shortcakes, whichever suits you best, whip the double cream until floppily thick. Just before you want to bring them out, split each shortcake across the middle, dollop some of the softly whipped double cream on to the bottom piece, cover with the scooped-out half (or whole if using smaller ones) of a passionfruit then set the top back on. Don’t squish it down: you’re after a jaunty, rakish angle. Proceed with the remaining five and set all six on a large plate, and let people help themselves as they want.

Serves 6.

RED ROAST QUINCES

When the two great Australian food writers, Stephanie Alexander and Maggie Beer, came to London some years back, I went to a dinner cooked by them; this was the pudding and I remain, all this time later, transfixed by it. Maggie Beer vaguely told me how she’d cooked them and I’ve hugged this information since then, longing to pass it on; this seemed the perfect opportunity.

It used to be that you could never lay your hands on a quince unless you had a tree, and so it was that the first thing I did when I bought a house with a garden was plant one, but now you can find them in Middle-Eastern stores pretty well off and on all year around, and in supermarkets for a few weeks from mid-August. Nothing matches their almost fantastically perfumed fragrance; and after this long, slow way of cooking them, their acid flesh turns to grainy, intense honeyedness, set to coral jelly at their centre, around the shiny black pips, the whole as darkly sticky as toffee apples. Serve these warm-to-room temperature, with a dollop of cold mascarpone on the side. Since cooking them takes almost 4 hours (though you are hardly involved) you’re really going to have to start the dinner’s pudding not long after you’ve cleared away lunch.

1kg caster sugar

5 quinces

1 litre water

mascarpone or crème fraîche, to serve

Put the sugar into a large, wide saucepan, cover with water, swirl to help the sugar start dissolving and add one of the quinces, cut up roughly. This is about the hardest thing you’ll be doing here: it’s a very simple recipe, but quinces are pretty well as solid as rock. Use a heavy, sharp knife and proceed with caution.

Bring quince, sugar and water to the boil and let boil away until you have a thick viscous syrup; this could take up to an hour.

Preheat the oven to 200°C/gas mark 6 and get out a roasting tin. Cut each of the remaining quinces in half, much as you would halve an avocado and put each one, cut side down in the tin. Pour over the syrup to come about 1cm deep and put the quinces into the oven for an hour. Turn the oven down to 160°C/gas mark 3 and cook for another 2–3 hours, basting (with the addition of more syrup if they’re drying out) and turning regularly so that they caramelise and colour on both sides.

Remove from the oven and set aside, cut side up, so that the oven-scorched, red-glazed quinces stand in their sticky, ever-solidifying syrup as they cool. Set each half on a small plate, along with the mascarpone or crème fraîche, as you serve and eat with a teaspoon, dipping first into jellied, grainy flesh and then into the sharp, coolly contrasting cream on the side.

Serves 8.

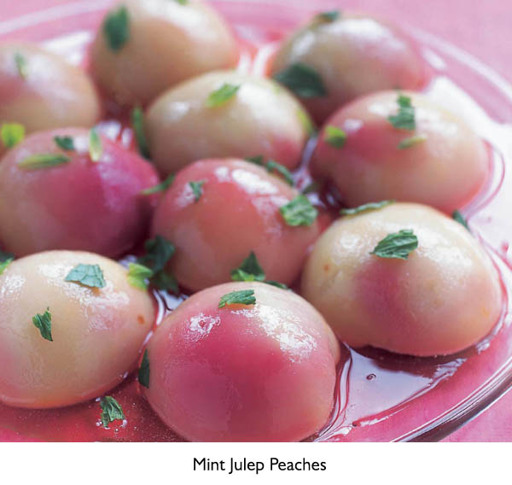

MINT JULEP PEACHES

There’s something about mint juleps that I associate with the deep heat of midsummer. I have to say this association is an entirely literary one: I’ve never sat in the wilting sun drinking a mint julep in my life; the most I can muster is a few in cold college rooms in my cocktail-drinking student years (which certainly dates me). But there is, I always remember, I hope not erroneously, from

The Great Gatsby

, that pivotal scene, when they’re all sitting around in the airless heat, deranged, before everything happens, drinking mint juleps. Anyway, there is something intensely summery – leafy, fresh, spicily aromatic – about these peaches, poached in sugar-syrup and bourbon and sprinkled with mint. Scotch whisky doesn’t seem to have the mellow, rounded spiciness of bourbon, but if that’s all you’ve got in the house…

700ml water

700g caster sugar

250ml bourbon

8 white-fleshed peaches

small bunch fresh mint

Put the water, sugar and 200ml of the bourbon in a wide-bottomed saucepan, swirl about to help the sugar start dissolving a bit, and then put on the hob over medium heat and bring to the boil. Let it boil away for 5 minutes or so and then turn the heat down so that the syrup simmers; you want pronounced but not fierce bubbles. Cut the peaches in half and remove the stones and then lower these halves, so that they fit snugly, cut side down, in the pan (I find I get four to six halves at a time, depending on the pan I’m using) and poach for a couple of minutes before turning them over and poaching for another 2–3 minutes cut side up; obviously, the ripeness of the peaches will determine exactly how long they need cooking. (And if the peaches are very unripe, it will be much easier to remove the stones after cooking.) The best way of testing the peaches is to prod the cut sides with a fork; you’ll be serving the fruit hump side up later and don’t want any fork marks to mar the pink-cheeked beauty of these pale-fleshed peaches.

When they feel tender but not flabbily soft, remove with a slotted spoon to a dish and continue till you’ve cooked all the peaches. Pour the juices that have collected in the plate – pink from the colour of the skins – back into the poaching liquid, itself blush-deepened from cooking the fruit, then measure 200ml of the liquid into a small saucepan. Add the remaining 50ml of bourbon to this pan, put on the heat and boil till reduced by about half.

While this is happening, carefully peel off the skins; this should be easy enough. And on cooking, you’ll see that the rosy fuzz leaves behind its markings on the white fruit, so that each peach half is tenderly coloured with an uneven pink.

You can leave the peach halves, cut side down, covered with clingfilm, on a plate till you need them. Should the peaches start turning brown on standing, just spritz with lime and their unsullied beauty will be restored.

Let the reduced syrup cool in a jug somewhere nearby; you can freeze the remaining poaching liquid to use the next time you want to make these (just top up with water and a dash or two of bourbon when you reheat). Before serving, pour some of the thick, pink-bronze syrup over the peaches and scatter the torn-off mint leaves, some left whole, some roughly chopped, on top.

Serves 6–8.

WHITE CHOCOLATE ALMOND CAKE

This is one of those dense, pudding-suitable cakes, known in America as tortes, in which ground nuts are used in place of flour. I’m not sure that you would, unless told, detect the presence of the white chocolate, but its vanilla-scent butteriness lends itself beautifully to the delicate nuttiness of the ground almonds. This is a cake that looks plain, but its rich, eggy, marzipan texture makes it anything but. To taste this at its summery best, serve a roughly thrown together salad of mangoes, spritzed with lime, and maybe even dotted with raspberries, along with.

175g white chocolate

150g soft unsalted butter

100g caster sugar

6 large eggs, separated

150g ground almonds

drop almond extract

to serve:

2 mangoes

juice of 1 lime

150g raspberries (optional)

Preheat the oven to 180°C/gas mark 4. Grease and line a 23cm Springform tin; if you’ve got some almond oil to hand, use that, otherwise butter is of course fine.

Chop the chocolate and melt it in a bowl over a pan of simmering water or for a couple of minutes or so on medium in the microwave. Don’t expect white chocolate ever to melt quite into the molten smoothness of dark: once it’s lost its shape, it’s melted enough; any more and it will start to seize. Put to one side while you get on with the cake.

Beat the butter until very soft, then add 50g of the sugar and cream again. Still beating, add the egg yolks one at a time, waiting till each one is incorporated before adding the next, then slowly scrape in the cooled, melted chocolate, beating firmly as you do so. Once the chocolate’s smoothly incorporated, add the ground almonds and the almond extract, beating again to mix.

Whisk the egg whites till peaks begin to form, then slowly add the remaining 50g sugar until gleaming, glossy and firm.

Add a big dollop to the cake batter and stir well to lighten the mixture, then fold in the rest, gently, in three to four parts.

Pour into the prepared tin, and bake for 45–50 minutes or until cooked through. You shouldn’t expect a plunged-in cake tester to come out exactly clean – this is, after all, a dense, damp sort of a cake – but no uncooked batter should be clinging to it. Anyway, when the cake’s ready it should be beginning to come away from the sides of the tin. You should check the cake after about 30 minutes, though, as at this stage of cooking you’ll probably need to cover the cake loosely with foil to stop it burning. Don’t worry if it’s caught slightly though: some bronzing at the top is a good thing.

Remove from the oven and sit the cake in its tin on a wire rack for about 20 minutes, before unspringing and inverting it, and letting it cool completely, though you can just as easily leave the cake in its tin, on the rack, to cool completely. This makes life much easier if you’re transporting it, which – if you’re picnic-bound, say – you might well want to.

Just before eating the cake, peel and chop up the mangoes roughly, wring out the mango skins over the fruit and add any mango juice that’s collected while chopping. Add the raspberries if using, and squeeze in the juice of half the lime. Taste to see if you want the remaining half squeezed over, too. Toss well, but gently, to combine and serve alongside the richly contrasting cake.

Serves 8.

ARABIAN PANCAKES WITH ORANGE-FLOWER SYRUP