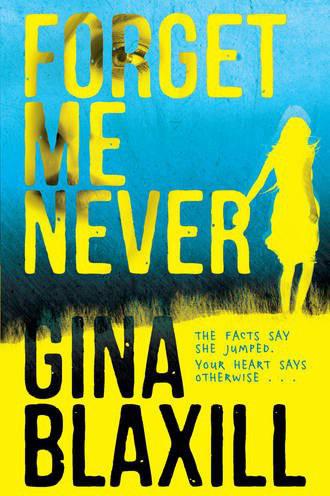

Forget Me Never

Authors: Gina Blaxill

To my brother Luke

Contents

My cousin Danielle was twenty-six when she died. According to the police she jumped from the balcony of her flat, which, in the words of my foster-mother, wasn’t a very

nice way to go. What a stupid thing to say. Is death ever ‘nice’?

My best friend Reece and I were the last people to see Dani alive. We’d been staying the weekend in her Bournemouth flat. I say her flat, but it actually belonged to Danielle’s

friend Fay, who was backpacking around South America and had said Dani was welcome to use it.

‘Come over! It’ll be brilliant.’ Danielle had sounded so enthusiastic when she rang to invite me. ‘Stay for a week, two weeks – I’m right next to the beach.

Loads to do. You’ll love it.’

‘I’ve got school,’ I said. ‘They probably wouldn’t approve of me taking a week out to splash about in the sea.’

‘Oh, yeah, school. Bummer. Well, whatever. Let’s make it a weekend.’

Timewise it wasn’t ideal – it was just after Easter, and GCSE exams were breathing down my neck – but I went anyway. My foster-mum, Julie, was fine with me going – she

said I deserved a break. I hadn’t heard from Danielle in ages, even though until recently she’d been working in north London, where I was living.

So after school on Friday afternoon Reece and I got the train from Waterloo and Danielle met us on the platform at the other end, all smiles and carrying an enormous bag of rum-and-raisin fudge.

She started chattering about the flat and the beach and her new job, which was a temporary one at an IT consultancy. We had fish and chips in town and then went for a walk along the seafront and

tried out the fairground rides on the pier. Danielle knew the people running the air-rifle stand and they let us have a couple of free shots, which they probably regretted when Reece started

arguing about the game’s rules. Reece had always liked the sound of his own voice – Danielle and I found the whole thing terribly funny and couldn’t stop laughing. It’s not

that remarkable, but I’ll always hold on to that moment: a summer night when the light was starting to fade, a warm breeze ruffling my hair, sharing a joke with my cousin.

On Sunday afternoon Reece and I were getting ready to leave when the flat’s doorbell buzzed. Danielle went to answer. I was in the other room at the time, so I don’t know if she said

anything to the caller over the intercom, but the next thing I knew, I could hear footsteps running downstairs.

‘Does she always rush about like that?’ Reece asked.

I shrugged. ‘Pretty much.’

Reece went to the window, pressing his palms to it. ‘She’s talking to some bloke.’

‘He’s probably just selling something,’ I said. ‘Give me a hand with my case, will you? The zip’s stuck.’

Half an hour later Danielle still hadn’t come back. She wasn’t outside the flat or picking up her mobile, so we had no choice but to head to the station. We’d booked two cheap

seats on the 4.37 and I couldn’t see Julie being happy about forking out for a later train.

‘Bit off, Danielle not coming to say goodbye,’ Reece said as we left. ‘She’s a bit of a skitz, your cousin.’

I felt a little disappointed that Danielle hadn’t returned, but it wasn’t as though it was the first time she’d let me down. She’d probably ring that evening, full of

apologies.

Later Reece and I worked out that Danielle must have jumped from the balcony roughly around the time we were changing trains at Southampton. When I got back Julie told me what

had happened.

I didn’t believe it at first. The idea that Danielle could be gone seemed impossible. But when I began to take it all in – well, it was pretty tough. The next few days were terrible

ones I’d give anything to forget. Over the years I’d become very good at blanking out feelings, but I couldn’t ignore this. Dani had been the only person in the world who was

mine, someone who knew exactly what I’d been through. She never judged me. She

understood

. That was something I could never replace.

The coroner was satisfied it was suicide. Danielle had never been that stable, I knew. She’d threatened to hurt herself before, and depression and mood swings ran in the family. Maybe it

had been one of those freak decisions you’d never make if you could go back in time. In the words of the police officer who’d come to tell me the verdict, it was ‘terribly sad,

but it all made sense’.

The whole thing left me reeling, but very slowly I began to accept that there was nothing left for me to do but try to get on with my life – without Dani.

And maybe that’s the way things would have gone if, four months later, I hadn’t found the memory stick.

Summer. Weeks and weeks off school. Sunshine, Cornettos and flip-flops. Holidays abroad for the lucky ones. Muggy days that feel endless, hanging out with friends in the park.

Fun. That’s what summer should be, but this year it just wasn’t working for me.

As well as coping with my grief I felt like I was at a crossroads, that everything was in flux. Everyone was waiting for their GCSE results. The exams had gone better than expected in the end,

but I still couldn’t see myself doing that well – English in particular had been a nightmare.

Half of my year at Broom Hill High were leaving to go to colleges rather than staying on for the sixth form, which didn’t have a great reputation. Lots of the teachers had gone on about

how A levels and BTECs were a huge stepping stone and how the subjects we chose now could determine the rest of our lives. I wasn’t sure I bought the idea that we were taking control;

everyone still treated us like kids. Especially me – as a foster-kid I wasn’t allowed to make my own decisions. I’d had to sit down with my social worker and come up with a

‘Pathway Plan’, supposedly to help me prepare for independent life when I turned eighteen and left care. Lorraine had strong opinions about what was best for me, and after a frustrated

hour of trying to explain I had no idea where I wanted to be in two years, I gave up and let her take over. Biology, geography and law A levels would be as good as anything else.

Apart from helping out in the Save the Animals charity shop, something I’d been doing on-off ever since I’d come to live with Julie almost a year and a half ago, I had very little to

do. I’d seen my old classmates down the high street. They’d invited me to join them, but after a couple of long afternoons sunbathing in the park I got restless. I’d rather be

doing

something. Hanging out is kind of empty when the people aren’t really your friends; nothing gets said that you remember, and time seems to drag. It was easier for them if I

wasn’t around, anyway; putting up with someone who’d had a family member die was a real downer. It would have been easier if Dani had been knocked down by a car or had some kind of

accident. That it had been suicide seemed to reflect on me somehow – especially as I had a reputation for being a bit crazy myself. The girls were clearly trying to treat me sensitively, but

that just smacked home how different I was from them. It made me feel I would never be a normal teenager again.

I kept wondering how the summer break would have been different if Danielle was still here. Maybe we could have spent the summer in Bournemouth, just us – hanging out in town, clothes

shopping, watching DVDs, the relaxed kind of stuff we didn’t always fit into the weekends and evenings we spent together. Dani could be very inconsistent, sometimes going into moods that

meant I wouldn’t see her for weeks. But the absent patches had been worth it for the good ones, when she would be incredibly sweet, showering me with gifts and affection.

Instead I had my classmates and lots of school gossip I didn’t want to hear. It just reminded me that I’d have to go back to Broom Hill, making me dread the end of the holidays even

more than I was already. It was times like these that made me wish Reece hadn’t left halfway through Year 10. Paloma, a girl who’d been in my class, had asked after him when I’d

joined her gang in the park recently. Everyone still remembered Reece. His run-ins with teachers were legendary. One particular highlight was the time he calmly walked out of a history lesson and

returned with an Internet printout that disproved what the teacher had just said about the causes of World War One. Reece had been excluded for that little stunt.

‘So,’ Paloma said, ‘you still talk? You and Reece used to be totally buddy-buddy.’

‘Yeah, well, that was before he buggered off to posh school,’ I said. I knew I was being a little unfair – Reece had kicked up a huge fuss about being moved to Berkeley School

for Boys, threatening his mother with a hunger strike and other ridiculous things. We’d stayed friends for a while, even arranging that Bournemouth trip so we could spend some proper time

together. ‘I’m fed up with him and his stupid new friends,’ I added.

‘Didn’t seem like he’d changed last time I saw him, a couple of weeks before my party,’ Paloma said. ‘You were matey enough then.’

I started to make a daisy chain, not meeting her eyes. There was more to our falling-out, but I wasn’t confiding in Paloma. I liked her best out of the girls from school because she stuck

up for me – Paloma was sometimes teased about her weight, so she knew a thing or two about fighting back – but she did have a big mouth. Eventually she got the message and changed the

subject, but I knew she’d try to get the full story later. When she invited me to the cinema the next day, I passed. Julie would have bugged me about that if she’d known. She was

worried I didn’t seem to have many friends. It wasn’t true – there were always people for me to hang out with if I wanted – but I just wasn’t close to anyone. Not like

I had been to Dani, or to Reece.

I think maybe the reason I don’t have many friends is that people are always so curious about my life. In the old days kids wanted to know what it was like to be in care, especially as I

sometimes exaggerated the less pleasant bits. More recently I guess people just noticed me because I was different. Once I skived off school and went to Hampstead Heath instead, but I didn’t

get into trouble. Broom Hill’s head teacher thought I was ‘troubled’, so he just sent me to have a long talk with the school counsellor. The other kids really resented that and

said I’d got off easy. I used not to care about gossip, because people said stuff about Reece as well, but it’s not so easy putting on a front on your own. Especially as since

Paloma’s party everyone really did have gossip about me. Horrible, embarrassing, true gossip.

Hendon, in north London, was where I lived. Reece used to say that if there was ever a nuclear war, the two things to survive would be Hendon and cockroaches, which tells you

quite a bit about Hendon. I didn’t think it was so bad – miles better than Hackney, where I used to live when I was being fostered by Mr and Mrs Ten Paces (whenever they went out she

always walked about ten paces behind him. I didn’t blame her – he was a bit weird, very picky about what she cooked for dinner, and he shouted at the telly a lot). Sure, Hendon had it’s

share of fried-chicken shops and launderettes and depressing, poky newsagents, but there was Brent Cross shopping centre nearby, some quite decent parks and a big aeroplane museum.

My latest foster-mum, Julie, lived on an ordinary back road in a terraced house. It was OK – always noisy, as the two other foster-kids were primary-school age, but I could go out if it

got too much. I’d miss it when it was time to move on. Julie had been very kind to me, especially since Dani died. When I’d mentioned I felt bad for not realizing how depressed Dani

must have been, something Julie said had really stuck with me.