Forgotten Voices of the Somme (36 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

We took prisoners, and we detached a lance corporal to take them back out of the line. I remember a young German prisoner, using a piece of wood as a crutch. I could speak a few words of German and I asked him how he felt, and I wasn't popular because I had him put on a stretcher and taken back behind the lines with the British wounded. It was probably the wrong thing to do, but he was a young fellow, not more than eighteen, badly wounded, and I suppose I felt sorry for him. There were a lot of British wounded, and others felt I was using up a valuable stretcher in looking after a German at the expense of a British man. Actually, I did hear stories of German prisoners being killed on the way back, so I don't know that he survived. I only know that I saw him set off from the trenches, to be taken back to the cages.

After the battle – I don't know why – I was made burial officer. The Newfoundland Regiment, all volunteers, had come to France and taken part in the attack of July 1. They had been chosen to attack Beaumont Hamel, which had been a fortress with its deep ravine and dugouts – and they were decimated. Some of them had been lying out here in no-man's-land since July 1, four and a half months previously, and I had the job of burying these dead, who were skeletons in uniform. The shape of the leg was quite round, with the shape of the puttee, until one stepped on it and one saw that the flesh was gone. A rat's nest was in the cage of each chest. The rats ran out as we shovelled them into shellholes. We took the pay books off them, but left their identity discs on, so that they could be identified later and given a decent burial. In the pay book, you might have the soldier's will, or pictures of his father, mother and sweetheart. We carefully put these pay books into sandbags, and shovelled the corpses into shell-holes, and covered them up as well as we could. We put up a bit of wood and made marks on it, to identify the place. The whole area had a sweet smell. The sweet smell of decaying flesh. I can still remember it.

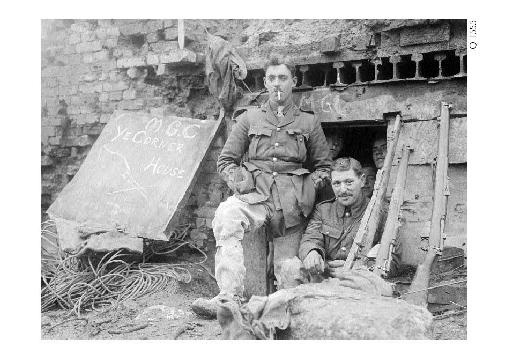

A machine-gun officer outside a German dugout captured in November.

After that, I went down the line with the sandbags full of pay books to Brigade Headquarters. There were two or three fellows carrying the bags, and we went down a communication trench to a very deep dugout, dug into the chalk. That was Brigade HQ, and it was very clean, and it was full of very smart staff officers with red tabs and well-polished Sam Browne belts. I was asked, very politely, to have a cup of tea, and they handed me some cakes which had come from Fortnum & Mason in Piccadilly. I was feeling a little under the weather, and it seemed strange that a short distance away the war was going on, but in this dugout you were back in London. They were all so clean, and I was dirty and lousy in my Tommy's uniform. I was treated very kindly by the supermen, but I wanted to get back. I handed over my pay books, said goodbye and went back up the communication trench with my little crew, and went back to the line.

I had two particular friends in the battalion, a lieutenant called

Smith and a lieutenant

called

MacLean. MacLean wa

s a divinity student – and what he was doing in the front line was anybody's guess. Smith was a dentist, who was going to go sick after the attack – if he survived – because he had a hernia that badly needed attention. He wouldn't go sick before the attack, because that would have been cowardly. Well, both men were killed in the attack. We buried the newly killed men from our battalion at a village called Mailly Wood. We buried them in one long trench, each one wrapped up in an army blanket, laid side by side. They were given a decent burial – we had the reverse arms, the bugle, the Last Post. I saw MacLean and Smith buried there, side by side. Later on,

Mailly Wood

cemetery was built, and they were all properly identified and properly laid to rest, with headstones.

Private Reginald Glenn

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

I used to play the organ for little religious services. One day, after our troops had gone forward and taken Serre village, the chaplain and another officer took me into what had been no-man's-land on July 1. We stood there, with all these skeletons lying around, and the officer said to the chaplain, 'Can we sing a little hymn over these bodies?' The three of us stood there and sang 'On the Resurrection Morning', and the next morning it snowed heavily and it covered all the bodies over. That was the start of the terrible winter.

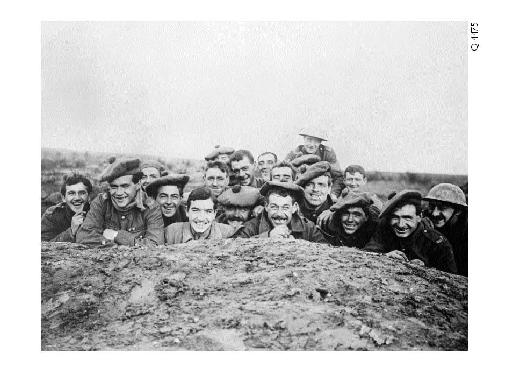

Gordon Highlanders

in a

reserve trench

at Bazentin-le-Petit in November.

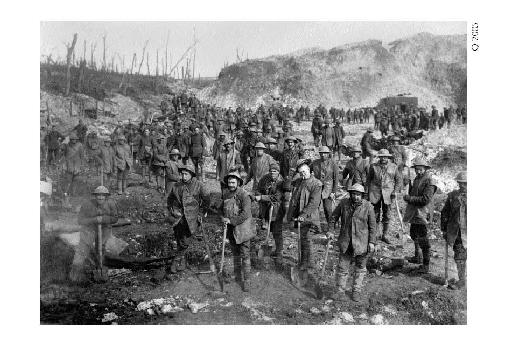

Working parties of British troops – photographed in November – inside one of the mine craters carved out by the explosions of July 1.

Major Alfred Irwin

8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment

On November 18, 1916, I was wounded in the assault on Desire Trench. In the morning, before it got light, I went up to look round this new ground we'd taken, and I went round with the company commander and was very pleased with the arrangements he'd made. Just as it was getting light, I started back to my battalion headquarters, and I hadn't gone more than a few yards when I was shot in the thigh. I fell into a shell-hole full of water and ice. It was freezing hard, and every time I raised my head the sniper had another go at me. So I had to lie in the water and wait for help, which came in the form of Canadian stretcher-bearers, later in the morning. When I was hit, I'd told my orderly to carry on back, but the unfortunate man was hit and died.

Corporal Jim Crow

110th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

We had a direct hit on a signalling dugout at Mouquet Farm. After that, the brigade medical officer said that every man in the division was unfit for service. That was at the end of November, and that's when I got out.

Looking Back

Half of the men, I'm sure, had no idea what they were fighting for.

By the end of the Battle of the Somme, 419,654 British and Dominion soldiers had become casualties, of whom 127,751 had been killed. There had been no Allied breakthrough, and 1917 would bring renewed bloody attritional struggles on the Western Front, at

Arras

and Passchendaele.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

The people at home did not understand the conditions under which we were fighting. I don't think they wanted to. Just as it's not fashionable now to talk about war – it wasn't then. It's a very strange thing. I've never told any of these stories to anybody before; people just don't want to know.

Major Murray Hill

5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

I've read the poems of Owen and

Sassoon

. I thought they wrote nonsense. Writing

poetry

about horrors. No point. It goes without saying. No need to write it up. Sassoon went off his head. He threw his medals into the sea. But he wrote a very good book about fox hunting.

Private Leonard Gordon Davies

22nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

I wasn't at all a brave man. I wasn't one of those who volunteered to go over the top, whenever there was a chance. It was an experience that you knew nothing about. You just jumped up on to the trench and hoped that you wouldn't meet a bullet. Actually going over, and seeing one man drop, and another man drop, and you'd wonder why you were still going. I always put it down to the prayers of my mother and father. But I didn't deserve to get through it all.

Private Donald Cameron

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

I wasn't frightened. I was bloody petrified.

Corporal Frederick Francis

11th Battalion, Border Regiment

A pal of mine was blown into a shell-hole and there was already a German in there. And they started to fight each other. To kill each other. But in the end, they gave it up and shook hands. They decided it was just a waste of life and they started talking to each other.

Corporal Wilfred Woods

1/4th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment

You didn't hate them as individuals, no, no, you felt sorry for them. I remember, on the Somme, in a German dugout there was this poor little drummer boy, about sixteen. He had been left behind in this dugout and he was scared stiff. We felt sorry for the poor little chap.

Private Harold Startin

1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment

There were no bitterness at all. There's many a German that helped our wounded people down the communication trenches, even carried them down. There were no hatred between the forces. Although we

were

shooting at one another.

Private Leonard Gordon Davies

22nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The trenches were very close together.

Vimy Ridge

was a very important vantage point, and both the Germans and us were at the top of it. The idea was to get the Germans off it. The fighting was extremely fierce, when it was on, but when it was off, it was very quiet. We were just fifteen yards from each other and we used to speak to them. They spoke quite good English. We agreed a ceasefire and we got out of the trenches and met each between the two trenches in no-man's-land. It wasn't very easy to get across, because there was wire in the way. I was smoking in those days, and they gave me some tobacco and we rolled it up into cigarettes. Then we got back into our trenches and we started to fight each other again. It had only lasted about five minutes. But we didn't shoot to kill, because we liked these people and they liked us as well.

It was a most extraordinary experience. It wasn't common. We must have been lucky to have particularly friendly opponents at that time. These were not military people by desire – one of them told me that he had been a waiter in London. The stupidity, the

absurdity of war

really struck me then, that this could happen, and the next moment you're trying to kill the man you've just been talking to. I began thinking it then, and I still think it. War is ridiculous.

Private William Holmes

12th Battalion, London Regiment

I look upon the war as an experience. I got just as much pleasure out of it as I did the bad times. I saw horrific things, but we were so disciplined that we took it all for granted, as though it was normal. When I came back, I was no different from when I went.

11th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment

I never regretted joining the army. We had some good times and we had some bad times, I remember every minute of it. Every night I go to bed and I think about it.

Private Fred Dixon

10th Battalion, Royal West Surrey Regiment

While I was on the Somme, life was absolutely miserable. After that, I was never the same man again. I was always looking to see how I could get away from the dangers. I wanted to live. I was never the same man again.