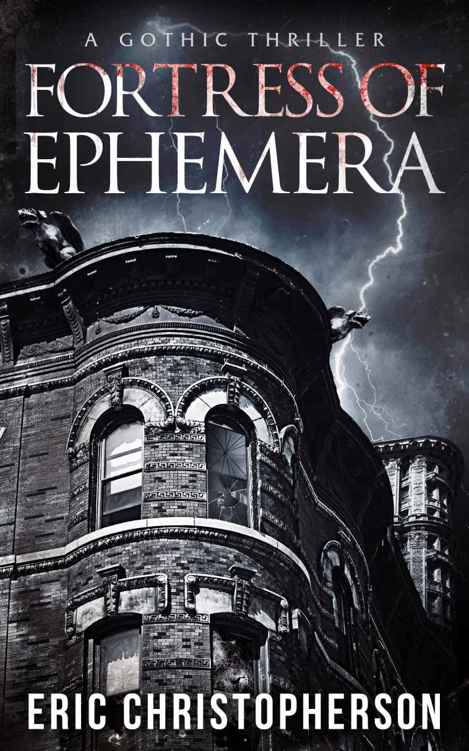

Fortress of Ephemera: A Gothic Thriller

Read Fortress of Ephemera: A Gothic Thriller Online

Authors: Eric Christopherson

FORTRESS OF EPHEMERA

by

Eric Christopherson

Also by Eric Christopherson:

CRACK-UP: A Psychological Thriller (4.5 stars, 47 reviews at Amazon US)

THE PROPHET MOTIVE: A Cult Thriller (4.2 stars, 62 reviews at Amazon US)

Bellevue Hospital

462 First Avenue

New York, New York

I, Miles Trenowyth, write down this record at the goading of Dr. Horace Dunn, practitioner in the newfangled black art of psychiatry. Robbed by an injury of my ability to speak (at least at this time), I have been induced to recount my story across these pages, to recall in detail that which I would smoke an opium pipe to forget—Hell, every pipe in Chinatown!—given the chance. I insist, as the price of my cooperation, that this account of my night in the Langley mansion on December the 12

th

never be copied, although the original manuscript may be shared with Detectives Brian McDonough and Christian Walcott of the New York City Police Department to help put an end to their murder investigation and spare me further official visits.

I demand, moreover, that this document be destroyed upon the conclusion of my treatment in a cleansing conflagration. I am to burn it myself on the day of my discharge from this cursed asylum, when entrusted again with the simple pleasure of striking my own match.

Miles Trenowyth, Esq.

December 22, 1919

Of the Inciting Incident of November 28

th

, 1919

Law Offices of Gaines, Trenowyth, and Fenno

I am by profession a civil attorney, specializing in litigation. Or at least I was until very recently. I am—was—a partner in the above-named Upper East Side law firm. One morning late last month, while still suffering from the previous night's intemperance, I staggered into the firm's outer foyer to borrow some aspirin powder from the receptionist, a Miss Althea Pimm.

Our offices are located on the ground floor, facing Park Avenue, and when the street door opened, it ushered in a blast of city noise along with a scrawny little man of advanced years, oddly appareled. With every step he jingled, as if his pockets were full of coins, though the source of his music proved otherwise.

“I wish to speak with Alfred Trenowyth,” he said without introduction or preamble. “I have urgent business.”

The bowler on his head was thirty years out of fashion, and he'd spoken as if

mon père

were still alive. I tottered across the floor at him, not entirely convinced of his materiality.

“I am Miles Trenowyth, Alfred's son. My father was a partner here, but he has been dead these past fifteen years.”

As the stranger contemplated this news, I peeked at his aforementioned

chapeau

, at his gray coat, buttoned high with a tiny collar, at his floppy black bow tie and billowy peg-top trousers. All products of a bygone era. As bygone as an old tart's innocence. And the condition of his attire—Let's just say Chaplin's tramp would not have swapped outfits with him.

“Dead?” he repeated. “How inconvenient.” The proper thing to say, I would soon learn, was not this man's

forté

.

“I suppose I feel the same way, Sir, concerning Father's unavailability. Is there something

I

could help you with?”

“Why, yes. I do hope so.”

I estimated his age at seventy-five, but he proved to be just sixty-three. His hair was the color of a dirty snow bank and fell all the way to his shoulders, by God. His un-waxed mustache and foot-long whiskers were of the same brown and white mottling. He reeked of something foul and musty and ancient. I fought the urge to wince, to backpedal.

“I presume you have a name, sir?”

He extended his hand. “Yes, of course. It's 'Noah Langley.' ”

It had been more than a decade, I am fairly sure, since I had even so much as heard the name Langley spoken aloud. So perhaps it is understandable—especially considering my sore, woozy head at the time—that Noah's surname meant nothing to me initially. But once he shared his home address in Harlem, recognition shone in my face with the speed of a maiden's blush.

“Why then you must be related to Colonel Langley?”

“His son,” Noah said with a slight bow.

“Then,” I said, admittedly flummoxed, “you are the grandson of Piers Langley?”

“Naturally.”

The colonel, a veteran of the Civil War, had been an amateur archaeologist of some renown—at least in his own time—and an inveterate traveler and collector of antiquities. His father, Piers, you'll likely recognize as the famous shipbuilder, among the first of America's great industrialists. So naturally my next thought was: Whatever on Earth could have befallen

this

Langley, this Noah, that he would be standing here before me under such reduced circumstances?

But the truth, I would soon discover, was that his circumstances hadn't reduced at all!

Why, you may ask, would a man of considerable—nay, vast—wealth keep himself, or present himself, in such a shabby state? Or why would he, as soon became evident, lead an impoverished, hardscrabble existence?

The answers await. But I am racing ahead in my story and must now backtrack to Noah Langley's urgent business. He summarized it as we continued to stand in the outer foyer. He had failed to pay his federal income taxes—since the very inception of the tax, imposed by constitutional amendment, you must recall, in 1913.

By this point, half a decade in arrears, he had ignored a steady blizzard of statements, warnings, legal notifications, and threatening letters and telegrams from the Bureau of Internal Revenue as well as official notices posted to his front door, the most recent proclaiming that his ancestral home had been decreed confiscated by the U.S. government to pay the back taxes and that the home's occupants—Noah, a bachelor, and his twin sister, Elizabeth, a spinster—were slated for eviction on November the 28th, or this very day. It had taken the arrival of two U.S. marshals and a passel of agents from the Bureau banging on his front door at seven-thirty in the morning to nudge Noah into action. Instead of greeting the eviction party, he had slipped through a rear door, which he described as “the old servants's entrance” because he no longer employed any staff, and set off to consult my long-deceased father, the first and last civil litigator he had ever dealt with.

“Am I to understand,” I said, “that these gentlemen stand now outside your home?”

“Or inside, given one of the marshals carried an axe.” Nasty weather swirled in Noah's eyes. “They've no right. You must put a stop to them.”

“Have you assets sufficient to meet your debt?”

“That is neither here nor there,” he said. “My first aim—should I find your fee reasonable—is for you to file some motion that will turn back the marshals and these Internal Revenue people, and the second is to have you argue my case in the courts—that I should be exempted from paying income taxes, as I don't work for a living.”

“Work doesn't play into it.” At times, I would find, speaking to Noah was like speaking to a wrinkly, hirsute child. “If you earn income—”

“I don't earn anything, it just accrues.”

“Nonetheless, you owe the federal government a portion of it. No other lawyer will tell you differently.” He stared off behind me, or nowhere. I tracked the storm in his eyes.

It died out suddenly at the sound of clock chimes announcing the start of a new hour. They came from a seven-foot tall antique oak grandfather clock a few feet behind Noah against the wall. He turned to it. “Beautiful piece. And what a lovely tone. Is that . . . is that a Willard?”

“A what?”

“A Willard? I refer to the Willard brothers of Massachusetts. Famous clockmakers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.”

“I'm uh, not sure.”

While he jingled over to examine the clock, I exchanged bemused looks with Miss Pimm. He stuck his nose up against the glass shielding the clock hands, peering inside for some clue, I suppose, that the instrument was indeed a Willard.

I cleared my throat to regain his attention: “So what is it you own then? Stocks, bonds, treasury bills, gold, silver, real estate?”

He shrugged. “I've a bit of each, I suppose.”

“Enough, I repeat, to meet your debt?”

He eyed me suspiciously. “It's possible.” Before I could ask why he had waited until the moment of eviction drew nigh before seeking legal advice and representation, he related that his sister, an invalid, was alone in the house and that “it would be most unsettling for her to be found by strangers and whisked out into the yard.”

“We should be off then at once.” I spun toward the receptionist—“Miss Pimm, my coat!”—then back to my wondrously weird new client. “Have you a buggy or carriage outside?” It was possible, of course, that he'd arrived by more modern conveyance, but given his outmoded attire, I assumed horse.

“No, I walked.”

“Walked? All the way from Harlem? From Fifth and One Twenty-Eighth?” A three-mile trek at least. “Why, man? When there are street cars and cabs at every turn?”

“A waste of money. I have two legs, don't I?”

“But then—” I recall sputtering for a tick and a tock, and when I found coherent speech again it was higher pitched and louder. “Why not simply telephone instead?”

“I haven't one. Not anymore. We rarely have the need for it, Elizabeth and I.”

Even you should be forgiven,

Herr

Doctor, if by this point you've leapt to the conclusion that Noah Langley was fabulously stingy like Ebenezer Scrooge, a rich old skinflint. Unlike the famous Dickens character, Noah's incessant appeals to the virtue of thriftiness were completely disingenuous. The object of thrift was—and he obliquely confessed this to me—an excuse for his true obsession (or compulsion), a sham justification that often satisfied the curiosity of strangers who found his behavior odd.

What then was his problem?

To stamp an understatement on it, Noah was a hoarder. To put it mildly, he maintained a series of collections, and his interests extended to all that is tangible on Earth, or so it seemed.

If it were possible to somehow collect the intangible—pretty thoughts, shades of gratitude, all the myriad forms of love, and so on—I do believe he would have proceeded.

Why? As best I can understand it, each new collectible satisfied some psychic itch that would nonetheless soon itch again. Conversely, it pained Noah no end to part with anything he owned, and this pain extended to collections animal, mineral and vegetable in nature.

Consider the repercussions a moment!

Now, perhaps, his extreme reticence towards spending becomes clear. For it wasn't merely the market value of money Noah loathed to part with—as it is for most of us—but the physicality of the cash or coin itself, its texture, weight, being, its membership in one of his collections, its idiosyncrasies. Hence, his utter frugality, the Victorian era clothing, the infrequent haircuts and poor, water-skimping hygiene, his slightness, his long walks and his tax rebellion and nearly everything there was to know about the man—or so I believed until December 12th, until that night of hell fourteen days later inside his ungodly house.

If only I hadn't interfered, but simply let the eviction stand. Good lives would not have been lost, nor such horrific memories gained. (To say nothing of this unwarranted incarceration.)