Fractions = Trouble! (3 page)

Read Fractions = Trouble! Online

Authors: Claudia Mills

Sit. Stay. Roll over. Shake paws.

Those were the tricks people taught their dogs. Wilson decided to start with shaking paws.

Those were the tricks people taught their dogs. Wilson decided to start with shaking paws.

He took Pip out of her cage and placed her on his bed.

“Pip,” he said. “Shake!”

Then he took her little paw and shook it.

He did it a few more times so she would get the idea and learn what the command sounded like. Each time, he said it slowly and clearly: “Sh-ake!”

He knew he was forgetting something. Oh, he needed to have treats, to reward her whenever she did it right.

Into her cage Pip went. Wilson ran down to the kitchen, grabbed a plastic bag of baby carrots, and ran back.

This time he offered Pip a nibble of a carrot right after he shook her paw.

“Shake!”

He shook her paw.

He gave her a nibble of carrot.

“Shake!”

He shook her paw again and gave her another nibble of carrot.

But Pip never offered him her paw, and that was what the trick was all about. The trick wasn't shaking hands with a hamster. The trick was getting the hamster to shake hands with you.

“Shake!”

Pip darted across Wilson's bed.

“Shake!” Wilson shouted after her.

Maybe two and a half weeks wasn't going to be enough time, after allâeither to train Pip or to learn fractions. Two and a half

years

wouldn't be enough time to learn fractions.

years

wouldn't be enough time to learn fractions.

Â

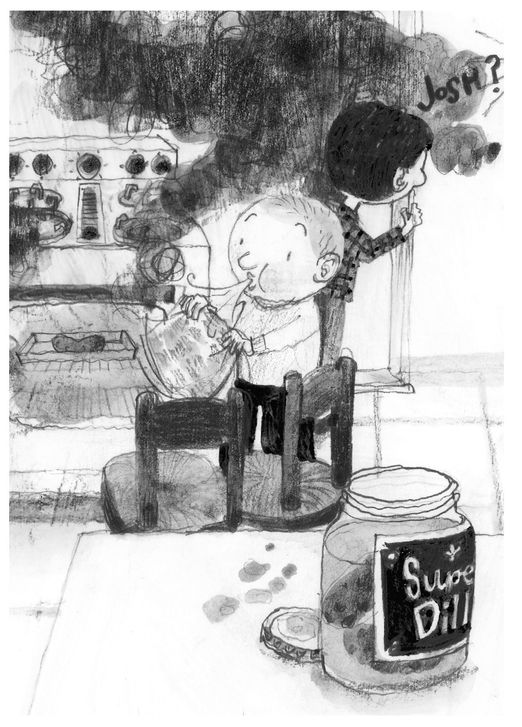

At Josh's house, after school on Thursday, Josh and Wilson selected the largest pickle from the jar of kosher dill pickles that Josh had made his mother buy. This was the pickle that was about to meet its doom.

“I still don't think this is a good idea,” Josh's mother said.

“That's what Einstein's mother said,” Josh told her. “Right before he discovered ⦠What did Einstein discover?”

“The theory of relativity,” Josh's mother answered automatically, as she gazed down at the pickle.

“Well,” Josh said, “your son is about to discover the theory of explosivity.”

Josh's father appeared in the doorway. Both of Josh's parents worked at home, doing something on their computers.

“Ramon, what if it does explode?” Josh's mother asked Josh's father.

“Well, it's just a pickle,” Josh's father said. “I don't think it will make a very big explosion.”

“The atom bomb was just an atom!” Josh's mom shot back. “And it made a very big explosion!”

Wilson was surprised that even as they kept telling Josh what a bad idea this was, they didn't tell him not to do it. His parents would have said, “No exploding pickles!” just as they said, “No video games! No TV on playdates! No fighting with Kipper!”

“Are you ready?” Josh asked his pickle.

The pickle didn't answer.

Josh apparently took that as a yes.

He put the pickle in a pan and slid the pan into the oven. Then he set the temperature to 350 degrees. That was the temperature for baking cookies, Josh had told Wilson. Since cookies didn't explode, that would be the temperature to start with.

Luckily, Josh's oven had a glass window in the door. Josh and Wilson pulled up two kitchen chairs and sat down in front of the oven to watch. His parents watched for a while, too, and then they drifted away.

When fifteen minutes had gone by, and the pickle hadn't exploded at 350 degrees, Josh turned up the oven to 400 degrees. He wrote down the temperatures and times in his science fair notebook.

Wilson saw Josh's title on the cover of

the book: “At what temperchur does a pickel explod?” Josh was as bad at spelling as Wilson was at math.

the book: “At what temperchur does a pickel explod?” Josh was as bad at spelling as Wilson was at math.

When the pickle didn't explode at 400 degrees, Josh turned the oven up to 425, and then to 450, and 500, and 550. Through the glass, the pickle was starting to look shriveled and shrunken in the middle, with brown patches all over it, as if it had a skin disease. But it still didn't look close to exploding.

“Maybe we should go play some video games in the basement,” Josh suggested. “If the pickle explodes, we'll hear it.”

“I think we should stay here,” Wilson said. “Besides, don't you think the pickle is starting to smell? Like it's burning, or something?”

The boys peered more closely at the pickle through the glass window. It was

definitely turning black. Smoke was pouring out from it, too.

definitely turning black. Smoke was pouring out from it, too.

Josh's mother ran into the kitchen, his father close behind her. The next thing Wilson knew, the oven had been turned off, the charred body of the pickle was in the sink under cold running water, and all the kitchen windows had been flung open to get rid of the smoke before the smoke alarm could go off.

“You could have set the house on fire!” Josh's mother said.

“That's what Einstein's mother said, too,” Josh said.

After his parents returned to their computers, Josh rescued the pickle from the sink. It was amazingly lightweight, a black pickle skeleton. He took a picture of it with his dad's digital camera.

“To put up on my science fair board,” he told Wilson. “I'll bring in the actual pickle, too. As evidence.”

“So I guess pickles don't explode,” Wilson said.

“Pickles don't explode in the oven,” Josh corrected him. “I'm going to give my parents a couple of days to get over this, and then I'll try it again in the microwave. Can you come over on Saturday morning?”

“Sure.” Then Wilson remembered. He had to go see Mrs. Tucker on Saturday morning. “I mean, no. I have something else I have to do.”

Josh looked suspicious. Wilson knew Josh knew that he didn't take piano lessons or play a spring sport, and he wouldn't have a dentist appointment on the weekend.

“What are you doing on Saturday?” Josh asked.

Wilson couldn't tell him.

“Just stuff.” Wilson gazed down at his feet. “Just some stuff my parents are making me do.”

Now Josh looked hurt.

“Okay,” Josh said stiffly, as he patted his burned, soaked pickle dry with a paper towel. “I guess I'll have to explode my pickle without you.”

By Saturday, Pip still hadn't learned how to shake paws or roll over.

At ten o'clock on Saturday morning, just as Josh's pickle was probably exploding in the microwave, Wilson presented himself at Mrs. Tucker's door. At least this time his mother and Kipper had stayed home to work on Kipper's science fair project, busy setting up all three tents in the backyard; the weather forecast was for a windy night.

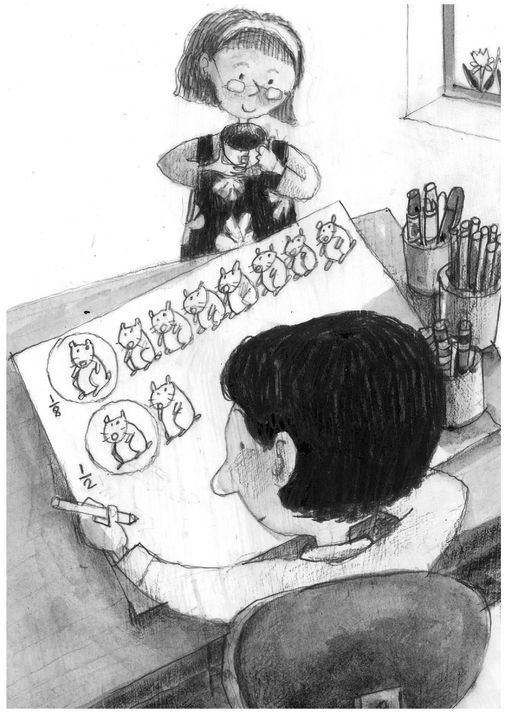

Wilson had wondered if Mrs. Tucker would ask him to draw hamsters again, and she did!

This time he drew a group of eight hamsters and a group of two hamsters. He could see that in the group of eight hamsters, one little hamster wasn't a very big part of the group. That was why

1/8

wasn't a very big fraction. But in the group of two hamsters, one hamster was half of the whole group. That was why ½ was a bigger fraction than

1/8

even though 8 was a bigger number than 2.

1/8

wasn't a very big fraction. But in the group of two hamsters, one hamster was half of the whole group. That was why ½ was a bigger fraction than

1/8

even though 8 was a bigger number than 2.

The bottom number in the fraction was for the size of the whole groupâhow many total hamsters. The top number told how many members, or parts, of the group you were talking about.

“Which one is the numerator?” Wilson asked.

“The numerator is the top,” Mrs. Tucker said. “The denominator is the bottom. Some people remember it this way. Since the numerator is on top of the denominator, this means that

N

for numerator comes before

D

for denominator. So you think of the words

Nice Dog

.”

N

for numerator comes before

D

for denominator. So you think of the words

Nice Dog

.”

“I wish it was

Nice Hamster

,” Wilson said.

Nice Hamster

,” Wilson said.

“Well, that could still be a good way to remember it, because

nice

comes first either way, and

nice

stands for

numerator

.”

nice

comes first either way, and

nice

stands for

numerator

.”

“I'm going to think that the Nice Numerator is on top, and the Dumb Denominator is on the bottom.”

“Wilson, that's wonderful!” Mrs. Tucker said.

As he was getting ready to go home, Wilson told Mrs. Tucker about the science fair. Pip was Nice, of course, but when it came to learning tricks, she was Dumb.

“What if instead of trying to teach her to do something, you just observed what she was doing naturally?” Mrs. Tucker suggested. “You could bring Squiggles home from school for the weekend and study both hamsters together. Try to find out what hamsters like and dislike. Are they affected by color? By sound?”

Wilson was impressed. “Do you tutor science, too?”

Mrs. Tucker laughed. “I tutor everything. The student who comes before you on Saturdays is coming for a few weeks for help with the science fair; the student who comes after you comes for help with writing. Just the way you like to watch Pip, I like watching the different ways that kids learn.”

Wilson felt better as he walked home. During his tutoring time he hadn't heard

any deafening explosions anywhere. Maybe he hadn't missed out on Josh's exploding pickle, after all.

any deafening explosions anywhere. Maybe he hadn't missed out on Josh's exploding pickle, after all.

Â

When Wilson got home, the backyard looked like a campground. Three tents were lined up in a row: the big, tall, family-sized tent; the medium-sized tent; and the small, low-to-the-ground tent moved from Kipper's bedroom. Wilson's mother was trying to explain to Kipper why he couldn't sleep in the tent now that it was set up outside.

“Tents are supposed to be outside!” Kipper said.

“At night little boys are supposed to be inside,” their mother said.

“But I have it all planned out. Snappy is going to sleep in the big tent, and Peck-Peck is going to sleep in the medium-sized

tent, and Pip and I are going to sleep in the little tent.”

tent, and Pip and I are going to sleep in the little tent.”

“Pip isn't sleeping in a tent!” Wilson interrupted.

“Pip isn't sleeping in a tent,” his mother agreed. “Pets like what is safe and familiar.”

Kipper pushed out his lower lip.

“Don't start that, Kipper,” his mother said. “Snappy may sleep in a tent. Peck-Peck may sleep in a tent. Pip is sleeping in her cage. You are sleeping in your bed.”

Then she turned to Wilson. “How was your time with Mrs. Tucker?”

“Okay.”

His mother had that hopeful look on her face again. “Do you think she's helping you start to understand fractions any better?”

Wilson shrugged. Mrs. Tucker

was

helping him. Now he knew that the nice numerator was on top and the dumb denominator

was on the bottom. And the big tent was

1/3

of the tents, while Snappy was ½ of Kipper's beanbag animals. And ½ was actually bigger than

1/3

, even though 2 was a smaller number than 3. But he didn't want to say any of this to his mom. What if she made him go see Mrs. Tucker three times a week?

was

helping him. Now he knew that the nice numerator was on top and the dumb denominator

was on the bottom. And the big tent was

1/3

of the tents, while Snappy was ½ of Kipper's beanbag animals. And ½ was actually bigger than

1/3

, even though 2 was a smaller number than 3. But he didn't want to say any of this to his mom. What if she made him go see Mrs. Tucker three times a week?

Â

That afternoon Kipper and his mom made sleeping bags for Peck-Peck and Snappy out of squares of felt. They folded the squares in half (fractions!) and then sewed up two of the open sides. Peck-Peck and Snappy got new pillows, too, also made of folded felt, stuffed with cotton balls. To cut out the pillows, Kipper's mom folded each square of felt in fourths (more fractions).

“You don't take pillows on a camping trip,” their dad scoffed. “On a camping trip you're supposed to rough it.”

Kipper ignored this remark.

Wilson had to admit that Peck-Peck and Snappy looked cute tucked into their matching sleeping bags with their little heads resting on their matching pillows. He almost made a sleeping bag himself for Pip, but she already had a cozy hamster “cave” just her size for sleeping.

At bedtime Kipper carried the two tiny sleeping bags outside and placed them tenderly in the tents, even though the wind was dying down. So

2/3

of the tents were now occupied.

2/3

of the tents were now occupied.

“I want to sleep in a tent,” Kipper begged one last time.

His mother refused to give in.

“You belong in your bed,” she repeated. “And you belong in it now.”

Wilson had hoped that Josh would call and tell him what had happened with the

pickle in the microwave, but he hadn't. Maybe Josh was still mad that Wilson had done his “stuff” instead, and hadn't even told him what the “stuff” was.

pickle in the microwave, but he hadn't. Maybe Josh was still mad that Wilson had done his “stuff” instead, and hadn't even told him what the “stuff” was.

Finally, just before his bedtime, he called Josh. He had to call him, anyway. It was Josh's weekend for Squiggles, and Wilson needed to ask Josh if he could borrow Squiggles on Sunday to work on the science fair.

“So?” Wilson asked, as soon as Josh picked up the phone. “What happened with the pickle? Did it explode this time?”

“Nah. This pickle got all wrinkled and weird-looking, and kind of brown and bumpy, but it didn't blow up.”

“So pickles don't explode.”

“Pickles don't explode in an oven, or in a microwave. Next I'm going to try

boiling

one.”

boiling

one.”

Wilson waited to see if Josh would invite

him to watch the thirdâand final?âattempt at a pickle explosion.

him to watch the thirdâand final?âattempt at a pickle explosion.

There was an awkward silence.

“What about you?” Josh asked. “Did you have fun doing your stuff this morning?”

“Not really,” Wilson said. “Oh, can I borrow Squiggles for a while tomorrow? I've decided I'm going to make my science fair project about seeing which color hamsters like best, and it would be better to do it with two hamsters instead of just one.”

“Sure,” Josh said. He didn't offer to come over to help with the testing.

Then, “Well, see ya,” Josh said.

“See ya,” Wilson replied.

Other books

Redzone by William C. Dietz

Poles Apart by Terry Fallis

Lucky Bastard by Charles McCarry

Officer Wolf (Sizzling Shifter BBW Romance) (With Bonus Book) by Sierra Burton

The Ties That Bind by Parks, Electa Rome

Die I Will Not by S K Rizzolo

Mistletoe & Hollywood by Natasha Boyd, Kate Roth

The Scent of Blood by Tanya Landman

The Cinema Girl (The Girls) by Vicente, S R

The Devil in Pew Number Seven by Rebecca Nichols Alonzo, Rebecca Nichols Alonzo