Free Lunch (28 page)

Authors: David Cay Johnston

On the other hand, the lucky few who have positioned

themselves to take advantage of the government rules are becoming fabulously wealthy under government policies that result in

taking from the many to benefit the few. Government policy has replaced legal limits on pay with sky's-the-limit pay plans that have

produced billion-dollar fortunes for the lucky few. It has made plundering public assets immensely profitable.

The idea of health care as a tax-free fringe benefit began with Roosevelt and the economic controls of World

War II. But the drive to make health care into a part of corporate America through government giveaways began with the Nixon era.

Those subsidies have grown from little weeds into a mighty forest of government giveaways to the few. Next, how health care

started down the road to high costs, frustration, and riches for the few by taking from the many.

22

LESS FOR MORE

F

RED W. WASSERMAN WAS MAKING A PRETTY GOOD LIVING

PROSPERING

in a career of his own design. He used what he had learned in public

health graduate school at the University of California at Los Angeles to show doctors and dentists on the affluent Westside of that

city how to make their practices more profitable. As he drove between their lavish offices overlooking the Pacific and their stunning

homes in the hills, he knew he would always do well, but it would take more to become fabulously wealthy. Then the federal

government dropped a golden opportunity into his lap.

Wasserman is a good place to start to

tell the story of the reasons Americans today find health care so expensive and so frustrating. He was at the cutting edge of

changes that transformed much of health care, which had been dominated by nonprofit hospitals and individual doctors, into a

for-profit industry whose largest customer is the government.

Over the past three decades our

elected representatives created, through a hodgepodge of laws, a health care system whose costs grow faster than the overall

economy every year. Greed goes unchecked. Theft remains largely unpunished. While supposedly promoting competition,

government rules encourage behavior that contradicts market forces. Wasserman grew rich playing by the rules the government

set and then managing successfully for more than two decades what government made possible for him. But those rules set in

motion a series of changes that now cost us dearly in both money and access to health care.

Just as Wasserman was getting going in 1972, President Nixon told Congress the country faced a health care

crisis. Too many Americans lacked quality health care and prices were rising too fast, he said. He pledged that his administration's

“highest priority” would be the “reform of our health care systemâso that every citizen will be able to get quality health care at

reasonable cost regardless of income and regardless of area of residence.”

Nixon said

publicly that competition provided by prepaid group health care plans would lower costs. This allowed him to sidestep calls for the

kind of universal health care every other modern nation was taxing its citizens to provide. In private, the Oval Office tapes show, he

said something quite different.

In a prepaid group health care plan, employers pay a fixed fee in

advance for all the health care their workers need. This was thought to explain why these prepaid plans had lower costs. Because

every dollar spent on care that could have been avoided through preventative care was wasted, doctors supposedly had an

incentive to keep people healthy. Dr. Paul Elwood, a Nixon administration official, coined the marketing term

health maintenance organization

to sell this idea to Congress.

Critics said the plans had low costs because they creamed the market, letting in mostly healthy people,

especially young workers with small children, and avoiding employers with older, sicker workers.

Prepaid plans went back decades. The best known was started by Henry J. Kaiser, the multitalented

businessman who made one of his fortunes during World War II welding together cargo ships in as little as a month at Marinship in

Sausalito, Calif. Kaiser realized he could efficiently provide health care to his workers by hiring doctors on salary to give his

workers any care they needed, charging the government a fixed price per worker.

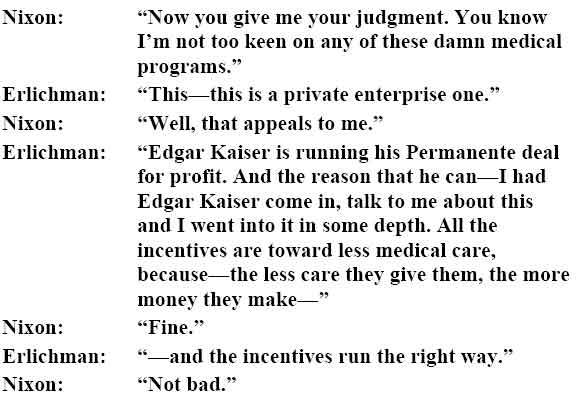

John

Erlichman, Nixon's domestic policy adviser, told the president in February 1971 that everyone on the staff except Vice President

Spiro Agnew agreed that the administration should tilt toward health maintenance organizations. Erlichman had just discussed

with Kaiser how the Kaiser Permanente system worked. Ignoring the “ums” and false starts, for the sake of clarity, here is how the

conversation recorded on the Oval Office tapes went:

The following year Nixon signed into law a requirement that large

employers offer a prepaid group health care plan, a health maintenance organization, or HMO, to their workers if they offered any

health plan.

Nixon's law to use HMOs to induce competition guaranteed loans and grants to

HMOs so they would have the capital to grow quickly. The market could not do this because by law HMOs had to be nonprofit and,

in some states, charities. In all, the federal government would put hundreds of millions of dollars into developing

HMOs.

Seeing subsidies move into a new health care market created by the government,

Wasserman decided to start an HMO. He took on a partner, Pamela K. Anderson. She had been his classmate in graduate school

and soon became his wife. It did not take much capital to get started. They put together $27,000 in savings and a $10,000 loan. Most

of their capital came from a $169,000 federal grant. They called their nonprofit health maintenance organization

Maxicare.

Wasserman recruited his clients to work as Maxicare doctors. To generate

subscribers, he approached two of the biggest employers in Los Angeles, the warplane makers Lockheed and Northrop. Both

companies were defense contractors, which meant Maxicare was really relying on the taxpayers for subscriber fees. It also meant a

generous flow of fees because no one spends, or wastes, money like the Pentagon. Under Wasserman's able hands Maxicare

prospered, quickly signing up hundreds of thousands of subscribers and earning solid and growing surpluses, the nonprofit term

for profits.

As a nonprofit, Maxicare was subject to supervision by the state attorney general in

his role as California's guardian of charitable assets. Any money left over once Maxicare paid its bills was held in trust for the

beneficiaries of the nonprofit and, ultimately, the public. The Wassermans earned big salaries as health care administrators, but

they could not get seriously rich. Then, eight years after Maxicare's founding, a new opportunity presented itself. Once again it

came from Washington.

President Reagan, declaring government needed to be tamped down

so markets could work their magic, signed a law in 1981 that phased out the government loans and loan guarantees for nonprofit

HMOs. Ever the entrepreneurs, Wasserman and Anderson decided to convert Maxicare into a for-profit business.

Back in 1981 few people thought they could make money converting a nonprofit into a business. Since then

the markets-are-the-solution crowd has changed our concept of what is nonprofit, even what is public service, pushing more and

more of our economy toward business. We now have a plethora of businesses whose revenue comes from the taxpayers, who

typically collect much more than they did when the work was done by nonprofits and the motive was not profit, but public

service.

Part of this trend that began in health care can be seen in the war in Iraq. From time

immemorial soldiers did KP (kitchen patrol) duty and washed their own clothes, putting idle hands to work. Today we pay

Halliburton and others, often under costly no-bid contracts, to feed soldiers. A Halliburton subsidiary was even paid $100 for each

laundry load it ran for soldiers in Iraq; soldiers were refused permission to do their own laundry or even to pay Iraqis, who

desperately needed the income. Likewise, in some cities sheltering the homeless has been turned into a profit-making business at

horrendously greater expense than having this work done by volunteer organizations, including churches and religious

charities.

The sale of nonprofit assets was not new, however. Under a legal principle in

common law for four centuries, anyone can buy any or all of the assets of a nonprofit organization, including those of a charity.

The rule was that the trustees had to agree to sell and that the buyer pay full value, in effect replacing the assets being purchased

with cash or something else of value. Nonprofits rely on this principle when they buy and sell stocks in an endowment or when

they sell their headquarters so they can move into another building. Say a buyer considered purchasing the Ford Foundation.

Virtually all of its assets are in stocks and bonds. If the Ford Foundation wanted to convert all of its assets into cash, anyone could

buy them. But it would make no sense to attempt to buy the Ford Foundation since it would be easier to buy the same portfolio of

securities in the market.

There was no market at that time to determine the value of an HMO's

assets, however. Despite this there were many ways that could have been used to establish the value of the HMO. Surplus (what a

business calls profits), cash flow, or return on assets could have been analyzed to set a price. There were other reasonable

considerations in setting the price, as well. What about the value of Maxicare's brand name? Its long-term contracts to serve

subscribers? Or could its price be determined by something as simple as how much cash the nonprofit had in the bank

overnight?

Wasserman and Anderson offered to pay $238,000 for Maxicare, roughly the cash

on hand. The trustees accepted, even though the couple was not willing to pay even that tiny sum right away. Instead, they bought

the nonprofit's assets for an unsecured, interest-only balloon note due in 15 years. The 8 percent interest rate was a steal because

at that time big banks charged their best corporate customers a prime rate of more than 20 percent. And the loan was interest only

for 15 years, when a balloon payment would come due.

Once that note was signed Wasserman

and Anderson became seriously rich. Before long they made a deal with Fremont General, an investment bank, for $16.5 million,

almost 70 times the value of the note that Wasserman and Anderson signed. Just seven years later, and after several acquisitions,

the value of Maxicare shares had soared to nearly $700 million. Wasserman and Anderson had pulled off an amazing deal. With a

cash cost of just $19,000 per year in interest payments, which were tax deductible, they ran a business worth two-thirds of a billion

dollars.

No major newspaper or magazine wrote about the conversion deal at the time in any

depth. The deal was too small to be on the radar of business reporters, few of whom back then possessed much understanding of

the nonprofit world. But in health care management circles, the word spread fast. Others who ran nonprofit HMOs began

maneuvering to get in on the easy money.

Among them was Robert Gumbiner, a California

pediatrician and Korean War veteran. In the sixties, Gumbiner started an HMO called the Family Health Plan in suburban Orange

County. On contract from the government, Gumbiner's organization provided prepaid government-financed health care for the

poor at low cost. Over the years, Gumbiner expanded to serve retirees on Medicare. As his reputation for quality care and efficiency

spread, so did his clinics. In time he had subscribers from Utah to Guam.

The idea of flat fees

paid in advance offended many physicians in conservative Orange County, who believed in charging fees for services because

they felt it made them beholden to no one. Some doctors shunned Gumbiner. A few called him a pinko. In time, however, his

maneuvers would prove that Gumbiner was really a master capitalistâor at least a master at getting government to make him

rich.

When it was legally a charity, Gumbiner treated the Family Health Plan like a personal

cookie jar, engaging in deals that directed money to himself and close associates. Funneling money to yourself from a nonprofit or

a government agency that you control can be a crime. At a minimum is a civil offense called

self-dealing.

Gumbiner's conduct did not sit well with Evelle J. Younger, a former FBI agent

who was the California attorney general.

When Younger's staff uncovered Gumbiner's

self-dealing, they did not file criminal charges. Instead, they treated it as a civil matter. A settlement in 1977 required Gumbiner to

return some money, but that was it. Despite his demonstrated proclivity for treating taxpayer and charitable funds as his own, all

Gumbiner had to do to remain in charge of the millions of government dollars flowing through the Family Health Plan's accounts

was promise to inform the attorney general of any major developments and agree to no more self-dealing. Even that gentle restraint

did not last long.

About the time that Wasserman and Anderson acquired Maxicare, Gumbiner

started negotiating to buy FHP's assets. Gumbiner and 17 other employee-investors agreed with the Family Health Plan board,

which he controlled, on a price of under $14 million. The board also defined a charitable purpose for the money, a purpose that, at

first blush, looked like a kindness to the poor. It was, but it was also a way for Gumbiner, who owned more than half the stock in the

new for-profit company, and his fellow investors to further enrich themselves.