Friends Like These: My Worldwide Quest to Find My Best Childhood Friends, Knock on Their Doors, and Ask Them to Come Out and Play (3 page)

Authors: Danny Wallace

Tags: #General, #Personal Growth, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Essays, #Personal Memoirs, #Humor, #Form, #Anecdotes, #Essays & Travelogues, #Family & Relationships, #Friendship, #Wallace; Danny - Childhood and youth, #Life change events, #Wallace; Danny - Friends and associates

“WHO GAVE YOU THIS?”

It was loud and aggressive and instantly I knew—it was Owen’s dad.

“Oh Christ,” I said.

We looked over the crowd, to the French windows. Owen’s dad, with a copy of Stefan’s book and a glass of something that looked

rather strong, was leaning over his son, demanding more information.

“OWEN—WHO HAS DONE THIS TO YOU?”

“Shit,” said Lizzie. “What did you write?”

I was panicking now.

“It was a joke!” I said. “It wasn’t meant in a bad way! He was rubbing donkey sausage in my shoes!”

Owen was now looking out into the garden, into the crowd, trying to pick us out, while his father flung Stefan’s book to one

side and tried to do the same…

“What did you

write?

”

I tried to think. What had I written? My mind was racing.

“I think he really thinks Owen wrote that note!” I said, terrified. “Why would he believe Owen wrote that?”

“Wrote

what?

”

“He’s going to see us in a second!”

“What did you

write?

”

I had to come clean.

“I wrote, ‘Dear Daddy, they have been feeding me booze. I am pissed off my tiny tits.’”

Lizzie looked horrified. She went into crisis-management mode.

“Just keep still and don’t look over at him,” she said, and so consequently we both instantly turned and looked straight at

Owen. He locked eyes with us and his little arm shot forward to point us out. His dad’s face turned to one of thunderous fury.

There was rage in his eyes and violence on his mind. Stefan and Georgia had heard the bellowing and were now upon him, calming

him down and asking what the problem was. Owen broke free and ran towards us.

“This isn’t looking very good,” I said.

“No, it’s not looking too good at all,” said Lizzie.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

“I’m not really sure,” said Lizzie.

We looked back towards Owen’s dad, who was now pointing us out and whisper-shouting at Stefan.

“I think it’ll be okay,” said Lizzie. “Stefan will simply explain the situation and how we would never give a five-year-old

booze, and—”

We looked down at Owen. He was standing at the buffet with a glass of red wine in his hand.

“Whose wine is that?”

I cried.

“I think that’s

mine!

” said Lizzie, her face suddenly white with terror. “I only put it down when we all hugged!”

“OWEN! YOU PUT THAT DOWN! YOU PUT THAT DOWN RIGHT NOW!”

Owen looked at me and smiled. Although Lizzie would later claim he did not, I

swear

to you it looked like he mouthed the word “numbnut” at me.

Lizzie started to walk towards him, but I pulled her back.

“Leave it! Don’t go anywhere near him! It’ll look like you gave it to him!”

Stefan was calming Owen’s dad, but Georgia was quick off the mark, replacing the wine with orange juice. But his dad hadn’t

finished.

“WHO ARE THEY?” he demanded. Everyone looked round. “THOSE PEOPLE HAVE BEEN GIVING MY CHILD ALCOHOL!”

Lizzie and I suddenly found very interesting things in the garden to turn and point at.

“I think maybe we should go,” whispered Lizzie.

“Yes, I think maybe we should,” I whispered back.

“How do we get out?” she said.

“I think we should simply walk past them with our heads held high,” I said. “And try to convey a sense in our general demeanor

that as responsible adults we would never feed a child alcohol.”

And so we turned, and we passed them, and it was only when we were in the hallway on the final stretch that we heard, from

the garden, and in a tone of disbelief and anger that lives with me to this day, the words: “POPPY’S FUCKING

GODPARENTS??

”

One minute I had been welcomed into the adult world, the next I had proved beyond all doubt that I just wasn’t ready for it.

But I

had

to be ready for it. I had to at least

pretend.

I knew something was wrong. I knew something didn’t feel quite right. But I didn’t know what it was. And not knowing what

it was really didn’t help me understand how to make it better.

Lizzie let me buy a packet of Doritos on the way home and I ate them on the bus. I told myself I would be fine, so long as

I never stopped eating Doritos.

A week or two later, I got a text from Ian.

IN WHICH WE LEARN THAT

NOBODY

MOVES TO CHISLEHURST…

L

ike its sender, the text had been fairly simple.

I have important news. We must meet up.

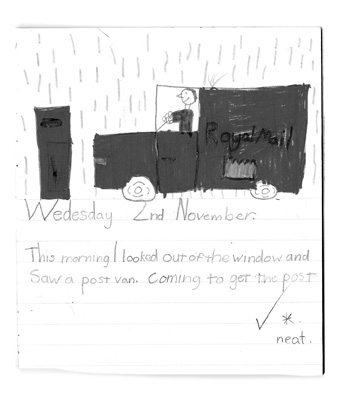

I had been in the queue at the post office when it came through. Someone had just coughed on the back of my neck and a large

woman was arguing with her dog. I’d texted back immediately.

All right then!

I began to wonder what Ian’s important news could be as I edged closer to the front of the queue. I like it when people tell

me they have important news. It makes me think they’re considering invading a country, or they’ve discovered the whereabouts

of an ancient scroll that will save all humanity. He texted back, mentioning neither scrolls nor invasions. Perhaps he was

being watched. We agreed to meet in an hour’s time at a pub near me.

“Next, please…” said the man behind the counter.

I handed him the slip of paper that had arrived through my postbox that morning. He disappeared for a few moments and came

back with a large and mysterious box.

The day just kept getting more exciting.

“Hello?”

“Mum?”

“Yes! Who’s that?”

“Your only son.”

A pause.

“Daniel?”

To be fair, I’d only given her one clue.

“Yes, it’s Daniel!”

“Hello, wee bean!”

My mum has a way of inventing names for me that have never before been said to anyone. Her strong Swiss accent somehow makes

them sound quite sensible, and she says them with such confidence you wouldn’t be surprised if heads of state used the same

terms when addressing each other at conventions. She doesn’t allow herself to be constrained by words that actually exist,

either, creating new ones out of the ether or inserting strange Swiss German nouns. In the past few weeks alone, I have been

greeted as Pomplesnicker, BimpleWicker and Bobbely. I got off lightly. My dad’s had thirty-five

years

of Minkeybips and Toodlebear. I’m not even sure if he knows his first name anymore. I’m not even sure if I do.

“Mum, did you just send me a massive box?”

“Oh

no!

” she said. “Was it

too

massive?”

She also has a knack of thinking everything is a potential disaster.

“No, it’s just the

right kind

of massive,” I reassured her. “But what’s in it?”

“Just some things we thought you might need. You know. We’re having a clearout at home, and we didn’t want to throw this stuff

out, and we thought it might be handy.”

“What kind of stuff?”

“Oh, you know. Old things we found in the loft.”

I’ll be honest—“old things we found in the loft” didn’t scream “handy.” Suddenly, opening a massive box—ordinarily a deeply

exciting moment—was something I didn’t mind putting off for now. So I thanked her, and promised I’d go through it all later,

and somehow managed to lug it all the way to the pub to meet Ian.

It had been a recent discovery, this pub. It had pot pourri in the toilets and a sausage of the week.

I liked it here. Everyone in it seemed to be very comfortable in their skin. They belonged here. And I wanted to belong, just

like them.

Once the shock of the events of Stefan and Georgia’s party had died down, I’d realized the only way to deal with what was

happening was to let it. To succumb to its inevitable, brutal force. To allow myself to be swept along on the crest of this

magnolia-colored, basil-scented wave. I’d just have to accept it. Stefan and Georgia thought I was ready. Lizzie thought I

was ready. Which meant: I was probably ready. And so, in the week or two before meeting up with Ian, I’d simply got on with

things.

Ian had looked suspicious when I finally saw him walk in. He didn’t recognize me at first because I was hidden slightly by

my copy of the

Guardian.

I called out his name, and three or four other men also reading the

Guardian

lowered their copies to look at him. They were all wearing similar glasses to me. Ian looked at them, and then at me, rolled

his eyes and sat himself down.

“So!” I said. “Important news!”

“Important news calls for important pints,” said Ian.

“They only do bottles here,” I said.

Ian shook his head, solemnly, and I went to get them.

When I got back, Ian was staring at my massive box.

“So what’s in it?” said Ian, poking at it with his finger, as if that would somehow tell him.

“Handy things,” I said.

“Gloves?” said Ian.

“Handy as in useful. I don’t know.

Maybe

gloves. My mum sent it.”

“How about the bag?”

He indicated the plastic bag next to it. This is Ian’s version of small talk. He’d be going through my pockets next. I opened

the bag and showed him.

“What in the name of

God

are

they?

” he said, peering in. “What in the name of

God

have you brought to the pub?”

“They’re coasters!” I said, delighted. “I just bought them!”

“Hide them!” he said. “Someone will

see

us. And please tell me they’re for Lizzie.”

“No. They’re mine. Well,

ours.

I bought them. They depict various different industrial scenes through the ages.”

“I can see that. Who are you? Your mum? Why’ve you bought coasters?”

“If we put them in the living room, they will offset the display cushions perfectly.”

“Right. You have

display

cushions?”

“We have two display cushions.”

“Do you sit on them?”

I put my finger in the air.

“They’re not for bottoms. They’re for display purposes only.”

Ian put his beer down and studied me carefully. He seemed a little annoyed with me. There was a silence. And then finally

he said, “So how are you, anyway?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “I’m fine. And you?”

“Very well.”

But he was still looking at me, suspiciously.

There was another silence. This was odd. Usually we never found it hard to talk.

I looked out of the windows, desperate for inspiration. Some children were kicking a cone. It reminded me of something I’d

just read in the paper.

“League tables!” I said.

“Football?” said Ian, confused.

“No, the schools one,” I said. “According to the latest schools league tables, the schools around here are well above average.

Although others are apparently

below

average. I think that means they average out.”

“So the schools around here are average?”

I nodded, eagerly.

“You are a deeply interesting man.”

I smiled a smile of gratitude. And then I realized he was being sarcastic and tried to subtly change it into a smile of annoyance,

but it just looked weird. Ian sat back in his chair and exhaled, heavily.

“Okay,” he said. “That’s it. My news can wait. Let’s deal with the matter at hand. What in the name of all that is right and

proper has happened to you?”

I blinked.

“How do you mean?”

“You’ve bought some coasters! You’ve got

display cushions!

You have made reference to an area’s

schooling!

”

“It doesn’t mean anything, Ian.” I shrugged, hiding the fact that I knew perfectly well it did. “And the cushions are just

a little cosmetic flourish.”

“

Cosmetic flourish?

What’s cosmetic flourish?”

I thought about it. What

was

cosmetic flourish? And what was I doing

talking

about cosmetic flourish?

“I don’t know,” I said. “I saw it on

Property Ladder.

”

Ian shook his head in disbelief.

“You’ve gone all old!”

“No, I haven’t!” I said, defensively. “And if I have, you have as well! We’re not getting any younger, Ian!”

I made a wise face and took a sip of my beer. I looked at the bottle and made a satisfied “Aah” sound. Ian put his head in

his hands.

“I have seen this happen before, my friend. I have seen this happen before and it’s dangerous.”

“Seen what happen? What’s dangerous?”

“This. You. Now. Approaching thirty. So-called ‘growing up.’ Buying things no normal man would ever want to buy. Making ‘Aah’

sounds. Using words like ‘flourish.’ It’s happening to you, Dan. You’re becoming one of Them.”

“One of

who?

”

“Them!”

“The New World Order?”

“No. The thirty-year-old married man who’s lost all sight of his sense of self! Look around you. Are we in the Royal Inn?”

“No.”

“No. We’re

not

in the Royal Inn, are we? We’re not in the same pub we’ve drunk in for the past who-knows-how-many years. We’re in some weird

gastropub in north London with ironic photographs on the wall, drinking Taiwanese lager. Look! Look at that sign! They have

a sausage of the week, for Christ’s sake! A sausage

of the week!

And it’s not even a

proper

sausage!”