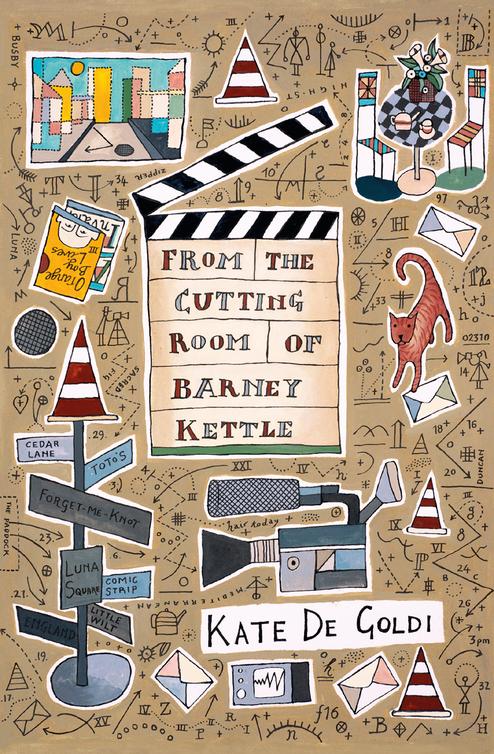

From the Cutting Room of Barney Kettle

Read From the Cutting Room of Barney Kettle Online

Authors: Kate de Goldi

B

arney Kettle knew he would be a very famous film director one day, he just didn’t know when that day would arrive. He was already an

actual

director – he’d made four fifteen-minute films – but so far only his schoolmates and the residents of the High Street had viewed them. Global fame was a little way off.

So begins the manuscript written from the hospital bed of an unnamed man.

He has written it over many months as he recovers from serious injuries sustained in a city-wide catastrophe.

He has written so he can remember the street where he lived, home to a cavalcade of interesting people, singular shops, and curious stories.

He has written so he can remember the summer before he was injured, the last days of a vanished world.

Above all, he has written so he can remember the inimitable Barney Kettle: filmmaker, part-time dictator, questing brain, theatrical friend; a boy who loved to invent stories but found a real one under his nose; a boy who explored his neighbourhood with camera in hand and stumbled on a mystery that changed everything…

A beautiful story: big-hearted, richly entertaining, powerful.

Kate De Goldi

For Rowan, who has always known thethrillingalchemy.

And in memory of Virginia, and the long-ago lost Christchurch days.

From the Cutting Room of Barney Kettle

(via the meticulously ordered files of DTS

*

)

To my dear Moo:

Happy Birthday.

Enclosed is my present to you, my best effort yet, I believe. Maybe this story will find a publisher. More importantly, it will find you. Of course, I will see you later today, but I wanted this to arrive in the mail. Always better to receive a parcel by post, don’t you think? Such a thrill.

It has not been easy writing from this prone position, and with fingers missing-in-action. But it is surprising what can be achieved with just two digits and a deal of determination. (Goodness me, an accidental alliterative outburst.)

As always, the nurses have been extremely kind. They have supervised the printing and postage. There are three copies: this one for you, one for the Kettle family, and a third for my files. My new files, that is. A foundation document.

I try not to think about the old files, Moo, but realism obliges me to conclude that they are now well and truly unreadable. They will be busily biodegrading, along with everything else. All the flowers and food and fabric in our apartment. (Oh dear, more alliteration.)

I hope there is not excessive alliteration in this story. I have tried to put into practice all the excellent tutoring and advice I have received over the years, and to follow the matchless example of

Mrs K. I have tried to write clearly and I have tried mostly to get to the point – but, I am who I am, and the affection for detail is hard to fight. Also, there were rather a lot of diversions along the way.

And sometimes the point is not clear until the end.

You will see I have put myself in the story, Moo, but how could I not? You are there, too, of course. And Mariko. And Albert Anderson and Sylvie and Izzy, Dick and Marie and Li Mai … well, you know the roll call.

And, of course, all the children.

Everyone

is there. All the animals, too, even the late-lamented Upside Down Catfish. Every shop front and potted plant on the Street is there, every brick chimney and weathered lamppost and arched window, every piece of carved stonework, every laneway …

Perhaps they are not all on the page, in black and white, but they are there nonetheless, behind the story, between the lines; they are there as clearly as they are in my poor old battered head.

Even the alarm clock is there. Ren was most insistent. Everything

there

and

then

, she said. Because this was a true story, she said. And, of course, it is.

In all the important respects.

So, dear Moo. Many happy returns, of one sort or another.

D

*

A little joke, Moo. This story is also my homage to the incomparable Mrs Konigsburg, RIP. It is proof that if you have read a beloved writer often enough they more or less take up residence inside you.

November: beginning with Barney

Barney Kettle knew he would be a very famous film director one day, he just didn’t know when that day would arrive. He was already an

actual

director – he’d made four fifteen-minute films – but so far only his schoolmates and the residents of the High Street had viewed them. Global fame was a little way off. It would come, though. Barney was certain about that.

Certainty was good. Certainty enabled you to make decisions and act swiftly. This was important if you wanted to be a famous film director.

Vision

was important too: that gave you a great sense of confidence and purpose. Then you could tell people what to do and how to do it. And finally – very tricky, this bit – finally you needed people to do exactly what you instructed,

immediately and without argument

.

These were the facts of film directing. Barney knew this

because he had read all the facts in

So, You Want to be a Filmmaker?

by Felix La Marche and Hal Nicholas.

So, You Want to be a Filmmaker?

was Barney’s filmmaking Bible. He had read it many times and for two years he had followed its instructions as if they were holy writ.

So, confidence and purpose and vision and action and instruction – they were all in the bag. (Barney thought of them as one long word,

confidenceandpurposeandvisionandactionandinstruction

). Unfortunately, the bit about people doing exactly what you instructed,

immediately and without argument

, was not at all sorted. Quite the reverse. More than once Barney’s cast and crew – aka, many of his friends on the High Street – had walked off his set saying, in their different ways, that he was rude and demanding and difficult to work with. Felix La Marche and Hal Nicholas had conspicuously failed to mention what a filmmaker did in these circumstances.

Barney’s sister, Ren, never walked off the set. She was a loyal and – you might say – a long-suffering assistant. But Ren certainly said what she thought. She was very forthright for an eleven-year-old.

‘You are a megalomaniac,’ said Ren, after the entire cast of

Feliz Navidad

had exited from the set. Edward, Henrietta, Jack, Benjamin, JohnLeo and Lovie all walked off down the Street together, a cross and plotting horde, heading to the Mediterranean Warehouse for gelato. It was very hot; they had been requesting a gelato break for more than an hour. It was Show Day, the first day of filming. Barney only had the three days of Show Weekend for filming because three-day shoots were what Felix La Marche and Hal Nicholas decreed. Time was of the essence. So, he had refused their requests.

‘Did you hear me?’ said Ren. She clenched her bulldog-clipboard and HB 5 pencil; she glowered at Barney through her thick-lensed glasses. Her eyeballs were globular and menacing like the Upside Down Catfish’s in the tank at Coralie’s Café. ‘You are a megalomaniac!’

Albert Anderson had said exactly this about Barney during his previous film shoot,

Silent Movie

. Everyone had walked off that set, too, when Barney had called them all lummoxes and lunkheads. Barney had retreated to Albert Anderson’s comic shop to discuss the persistent unreasonableness of his cast and crew. (There was just one crew member: JohnLeo. He hardly ever talked; he preferred to view the world from behind the scenes.)

‘You have many splendid qualities,’ said Albert Anderson. He was opening boxes of new issues, wielding his Stanley knife with unnerving vigour. The boxing tape sprang apart and waved in alarm. ‘But,’ said Albert, ‘you are also a bit of a megalomaniac.’

‘A

bit

of a megalomaniac?’ said Mum, later. ‘Albert’s far too generous.’ Mum had once described Barney as a budding dictator with delusional fantasies of omnipotence – which was another way of saying Barney liked to get his own way about everything. She could spot budding dictators, she said. The minute they started school. Mum was a teacher.

‘All great and famous film directors are megalomaniacs,’ said Barney to Ren as they stood in Little Wiltshire Park on that hot November Friday. The props of

Feliz Navidad

were strewn about them: a tandem bicycle; a 1950s perambulator; a baby’s mattress and pillow; a large hay bale.

Feliz Navidad

was a Nativity with a difference. Mary and Joseph had arrived at a cowshed on a 1920s bicycle made-for-two instead of a first-century donkey.

Unfortunately, on arrival they had got rather carried away and barged straight into the hay bale, semi-destroying it. At that, Mary and Joseph – aka Lovie and Jack – had tumbled from the tandem and rolled around on the ground laughing uproariously. Everyone else had rolled around too, quite out of control, bleating for gelato. This was when Barney had lowered his video camera and begun raging.

‘It’s the only way to get things done!’ said Barney to Ren. ‘It’s part of the job description!’

Felix La Marche and Hal Nicholas had affirmed this in

So, You Want to be a Filmmaker?

A good film director could not afford the luxury of pleasing people, they wrote. A good filmmaker had a job to do. If you wanted friends, wrote Felix La Marche and Hal Nicholas, try some other business. Cosmetic surgery, for instance. Stand-up comedy. Librarianship.

While his mutinous cast ate gelato Barney fled once again to Albert Anderson who was in Coralie’s Café at his corner table, playing chess with Shota, one of the Polytech jazz students. Albert was accustomed to Barney’s filming dramas. He was wonderfully tolerant and unflappable; he was always ready to listen.

‘Why couldn’t they be more serious?’ wailed Barney. ‘Why couldn’t they just cooperate?’ If things went smoothly then he, Barney, was so much better to work with. It was that simple. Couldn’t everyone see that? If he was getting film in the can he was happy. If he wasn’t doing that, he wasn’t

living

. Barney spat out the word

living

much like a stricken operatic tenor. Albert Anderson’s dog, Art, dozing beside his master, raised his head drowsily from his paws at the sound of Barney’s distress. Barney slumped in his chair and into the silence of Albert Anderson’s corner in Coralie’s Café, waiting for Albert to offer comfort.

‘But life isn’t always about

doing

,’ said Albert Anderson, after some time, long enough for Barney to become distracted by Shota’s shoes. They didn’t match. The left foot was brown leather with laces. The right was a black sneaker with a hole in the toe. Barney could see Shota’s big toe beating time to some inner chess-playing soundtrack. ‘Sometimes,’ said Albert Anderson, ‘you just have to be.’

‘Be what?’

‘Just

be

. Exist. Dawdle. Look and listen.’

Albert Anderson stared at the chessboard as he spoke, practising what he preached. He’d been studying the board the whole time, contemplating his next move. Shota was one of his better opponents.

‘I don’t have time to dawdle,’ said Barney, crossly. ‘Time waits for no man.’ He’d heard that somewhere.

Albert Anderson squinted at the board.

‘Time marches on!’ said Barney. He’d heard that somewhere, too.

‘Maybe,’ said Albert Anderson. He touched a black bishop’s mitre with the tip of his forefinger. ‘Sometimes time can be slowed down, though … by just sitting still.’

Albert Anderson said these last four words slowly and silkily and at the same time he slid his bishop towards its prey. Shota’s smooth brow furrowed minutely.

‘

Or

,’ said Albert Anderson, bestowing a crocodile smile on Shota. ‘You can, how shall we say,

capture

time. As in novels. Or paintings. Or comics, of course – comics are very good with time. And let’s not forget film, Maestro!’

He grinned at Barney and Barney almost grinned back. He

did

like it when Albert Anderson called him Maestro. But.

‘Films

eat

time!’ said Barney. ‘That’s my whole point. I need all the time I can get. And when you make films you absolutely need everything to go your way. I mean everything. Otherwise it

wastes

time.’

‘Then you’ve got a good old paradox on your hands,’ said Albert Anderson, serenely. He studied the board again. ‘Takes time to preserve time. Minus and plus. How

interesting

.’

Not really, thought Barney. He glared at Albert Anderson’s bent head. Albert was no use at all when he waxed philosophical.

‘Go for a walk, Maestro,’ said Albert Anderson, watching Shota decisively move his knight, a dog’s leg to the left. ‘Take some deep breaths. Then go and apologise to your cast.’ He always said this.

‘A director shouldn’t have to apologise,’ said Barney. He always said this, too.

Barney pushed back his seat and stood before the chess table. ‘A director needs to be in

charge

. A director needs to show who’s boss. It’s exactly like having a puppy.

‘The cast are the puppy,’ he added, in case Albert Anderson and Shota hadn’t quite understood.

But, at this, Shota and Albert Anderson became convulsed with laughter. Their faces creased and warped. Their shoulders shook. Their hands knocked the board and pawns scattered.

Lummoxes, thought Barney. Lunkheads.

‘Maestro,’ said Albert Anderson, realigning chess pieces, his fingers trembly with mirth. ‘Oh Maestro. You’re the best.

The cast are the puppy

. I’ll treasure that. It can be the title of your memoir.’

‘I’m going,’ said Barney.

He picked up his camera bag, slung it over his shoulder and walked from the chess table with a stiffened back. He made what he considered a rebuking exit through the swing door of Coralie’s Café, out into the High Street.

The High Street rebuked Barney right back. Out there the sun was shining. The sky was cloudless, the air warm on bare arms. It was a perfect summer’s day.

The footpaths were crammed with shoppers and children and entertainers. The air was busy with sounds: idling cars and horn blurts, shouts of laughter, Christmas tunes from the jazz students busking at each end of the Street, the choir of starlings in the big horse-chestnut tree. It was the usual scene, far too carefree and joyous for Barney’s mood.

Over the road, in the midst of the bustle, beneath the blue awning of Bambi’s Health Store, Bambi herself was hanging the final ornaments on her large potted Christmas tree. Bambi’s Christmas tree always appeared at Show Weekend. It was a traditional fir and perfectly shaped, though the decorations were rather eccentric: long red jalapeño chillis and paua shells polished to a high gleam, flashing now in the sunlight. It was a Euro-Latino-Pasifika Christmas tree, said Bambi. Last year, there had been a large photograph of both the tree and Bambi in the newspaper.

Barney smiled. He didn’t mean to, he didn’t

want

to. The tree made him smile, and Bambi did, too. She looked so much like a Christmas decoration herself in her shimmering red top and green harem pants. Her abundant gold hair was tied in a topknot and skewered by two black chopsticks. Bambi’s feet were bare, but her toes were ornamented with rings. Barney couldn’t see the toe rings, but he knew they were there. The thought of the toe rings made him smile, too. There was one with bat wings.

That was the good thing about Barney. Perhaps he was a bit of a megalomaniac. Perhaps he did have the occasional delusional fantasy of omnipotence. But he could never be angry or annoyed or sulky for long. It was a great nuisance, really. In the middle of a full-blown, well-earned, solid black mood, something was apt to catch his eye and his interest; something distracted him and made him puzzle or laugh, and the next minute his fury was leaking away.

It happened now. The sight of Bambi and her multi-cultural Christmas tree was irresistible. Barney’s bad mood popped like a balloon under a pin.

He would go and apologise to his friends, he decided. He would have a gelato, too. One scoop raspberry, one scoop lemon. And then they would resume filming.

But first.

Barney let the camera bag strap slide from his shoulder and come to rest on the ground. He bent down, took his video camera from the bag and pushed the lens cap lever. It was a familiar series of moves that always made his blood hum. The clink of the metal bag-catch. The snap of the lens cap opening. And then his favourite sounds: the pinging note when you pushed the switch from Off to On and the whirring of the cassette tape engaging.

Now we begin

the sounds seemed to say …

Behind him, the swing door of Coralie’s made its low groan-and-swish as someone came out of the café, but Barney paid no attention. He was absorbed now, fully focused, you might say.

He swivelled left to face the south end of the Street and pointed the camera at the rainbow bunting strung across the frontage of the Yoga Room (est. 1985). He held the frame on the old stone letters curving above the trio of arched windows: C F C o t t e r & C o. Then he slow-panned all the way down the east side of the Street to His Lordship’s where Dick Scully was hosing the second-storey windows, his dog, Kiwi Keith, by his side, nose upwards, tongue out, catching the waterfall. Barney filmed Dick and Kiwi Keith for ten or so seconds then brought the camera slowly back again to Bambi and her Christmas tree.

He zoomed in on Bambi’s freckled arms. They stretched upwards, her fingers straining to fix the star to the top of the tree. It was a tin star, painted in gold glitter, a loop of wire at the back for hanging. All the children in the High Street had helped make the star four years ago. Barney had soldered that wire loop.

Barney watched Bambi’s fingers not-quite-reaching the top of the tree, her arms drooping and extending and drooping again. He willed her arms upwards. He held his breath as Bambi’s fingers wobbled and flailed and still fell short.

And now – oh, it was so much more mysterious, so much more magical through the lens of a camera – now there was another arm coming into the frame, a jacket-covered arm with a big hand that plucked the star from Bambi’s fingers and looped it neatly over the pale green sprig at the top of the tree.

Barney moved the camera down the arm and onto the face of the knight-in-shining armour. It was Suit – of course: no one else would be wearing a jacket on such a hot day. He was wearing a buttoned shirt and tie, too. Barney held the camera on Suit as Bambi flung her arms around his neck and bounced a little on her bare feet, springy with gratitude. Suit stood stiff as a mannequin, his arms by his side, his face startled under a barrage of Bambi’s kisses.