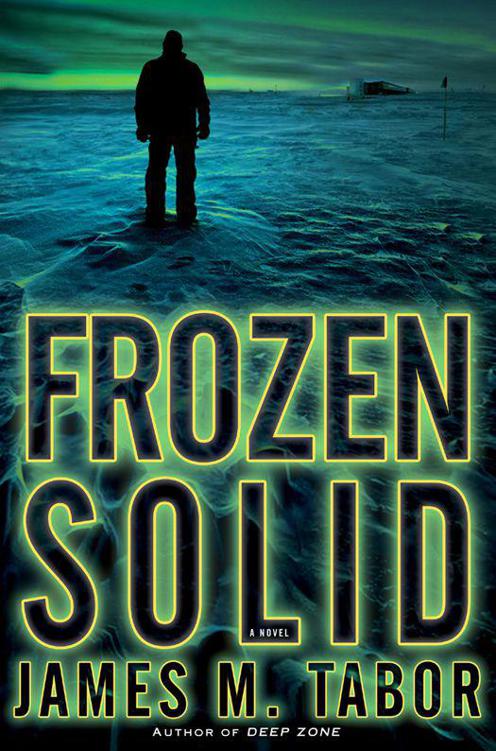

Frozen Solid: A Novel

Read Frozen Solid: A Novel Online

Authors: James Tabor

Frozen Solid

is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by James M. Tabor

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B

ALLANTINE

and colophon are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Tabor, James M.

Frozen solid : a novel / James M. Tabor.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-345-53885-7

1. Women scientists—Fiction. 2. Bioterrorism—Fiction.

3. Overpopulation—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3620.A258F76 2013

813′.6—dc23 2012051358

Title-page photograph: © iStockphoto

Jacket design: Carlos Beltrán

Jacket photographs: © Calee Allen

v3.1

Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.

—

EDWARD ABBEY

We must shift our efforts from treatment of the symptoms to the cutting out of the cancer. The operation will demand many apparent brutal and heartless decisions. The pain may be intense.

—

DR. PAUL EHRLICH

,

Bing Professor of Population Studies,

Stanford University

SETTING UP ITS FINAL APPROACH, THE C-130 PITCHED NOSE DOWN

and snapped into a thirty-degree bank, giving Hallie Leland a sudden view of what lay below. It was the second Monday in February at the South Pole, just past noon and dark. Two streaks of light, thin and red as fresh incisions, defined the runway. Half a mile distant, the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station appeared to float in a glowing pool. The air here was clear as polished glass, red and white and gold lights sparkling jewel-sharp a full mile below.

“Pilot having a bad day?” Hallie yelled at the loadmaster, the only other passenger. Glum and silent, he had spent the flight reading an old issue of

People

magazine. The peace had been unexpected and much appreciated. She’d been traveling for four straight days and nights, and her need for sleep was like a desperate thirst. But the aircraft was designed for cargo, not comfort. Her seat was nylon webbing that hung, hammock-like, along the entire length of the fuselage, and four roaring engines made seeking sleep like trying to doze behind a waterfall. So for most of the flight’s three hours she’d alternately revisited the bad parting from Wil Bowman at Dulles and tried

to visualize diving a subglacial lake with twenty-two-degree water—her primary reason for coming here.

“Just a little fun.” A bit more cheer in the loadmaster’s voice. “It gets boring, flying McMurdo to Pole and back. Plus, if he goes in, there’s just them up front and us two back here. Know what I mean?”

She wasn’t sure she did. But she was watching, down on the ice, a clump of white light break into jittering pinpoints. “What’s that?”

“There’s a Polie saying: ‘Two best days of your life are the one you fly in and the one you fly out.’ Lot of happy flyouts down there.” He peered at her. “We don’t usually get incomers this late. You a winterover?”

“Looks like you’ll be full heading back to McMurdo.”

“Tell me about it.”

“You don’t sound happy.”

“Most’ll be drunk before they get on. Always a lot of throwing up and fistfights and such.”

“Drunk? It’s noon.”

He looked at her. “First time down here?”

The cowboy up front could fly, Hallie gave him that. She barely felt the Herc’s steel skis kiss the ice, no easy trick with sixty tons in the scant air of thirteen thousand feet. The plane taxied, stopped, lowered its cargo ramp. She paused at the top to don a face mask and pull up her fur-trimmed hood.

“I wouldn’t linger, ma’am. They’ll run you right over.” Beside her, the loadmaster gestured toward the mob down on the ice.

“Sorry. You don’t see that every day, though,” she said, looking up at the southern lights, unfurling like green and purple pennants across the black sky.

He frowned, hunched his shoulders. “Not supposed to look that way at noon.”

On the ice, a wall of bodies in black parkas blocked her way, faces hidden behind fur ruffs, headlamps on top, fog of liquor breath. The

pack shuffled and stamped like horses at her family’s farm in Charlottesville.

“Coming through, please,” Hallie called.

“… come through

you

,” somebody slurred, and a few people laughed, but nobody moved. She walked around them. The loadmaster yelled, “Board!” and jumped aside like a man dodging traffic. Eventually, he dragged her two orange duffel bags down onto the ice.

“Welcome to hell froze over, ma’am. Enjoy your stay!” the loadmaster exclaimed. It was the first time she had heard anything resembling good cheer in his voice.

“How come you’re happy now?” she yelled.

“Ma’am, ’cause I’m flying outta here.”

She watched the plane claw its way back into the thin air, turn toward McMurdo, and then she was alone on the ice. She had never been in a place that looked and felt so hard. The sky shone like a dome of polished onyx etched with the white flecks of stars. The ice could have been purple marble, scalloped into sastrugi. The wind was blowing twenty miles an hour, mild for the Pole, where a thousand-mile fetch delivered hurricane winds all too often.

A digital thermometer hanging from one zipper pull read sixty-eight degrees below zero. The windchill dropped that to about one hundred below. She had heard firefighters describe fire as a living, hungry thing. This cold was like that, seeping through her seven layers of clothing, attacking seams and zipper tracks and spots of thin insulation. The exposed skin on her face felt as if it had been touched with lit cigarettes.

It occurred to her that she could die right here where she had deplaned, with the station in plain sight. She decided that all the sages were wrong about hell. It would not be fire. It would be like this. Cold, dark, dead. She rotated 360 degrees, saw nothing but the station. In this pristine air it looked closer than a half mile, but she knew the distance from maps at McMurdo. She kicked the ice, scarred and dusted with chips like a hockey rink after a game. Her head felt light and airy; silver sparks danced in her vision. Her ears were ringing, she

was nauseated and short of breath, and her heart was pounding. Altitude, Antarctic cold, exhaustion—and she had just arrived.

She had brought her own dive gear, and each duffel weighed forty pounds. At this temperature, the ice was like frozen sand. Dragging the bags was going to hurt. She had made this trip on short notice—no notice, really, for such was the life of a BARDA/CDC field investigator. But it was still bad form, she thought, letting a guest freeze to death out here.

“Let’s go, then,” she said. Inside four layers of gloves and mittens, her hands were numbing already. She managed to grab the bags’ end straps and headed for the station, hauling one with each arm. It was like trudging through deep mud—at altitude. After thirty steps she stopped, lungs heaving, muscles burning, body cursing brain for making it do this mule work. The station seemed to have receded, as if she were drifting away from it on an ice floe in black water, like Victor Frankenstein’s pathetic monster.

She looked up and saw a light detach from the distant glow and dance toward her. Several minutes later, the snowmobile slewed to an ice-spraying stop. Its operator was about the diameter of a barrel and not much taller. He was all in black, right down to his boots. She kept her headlamp trained on his chest to avoid blinding him.

“It was getting cold out here. I didn’t expect a marching band, but—”

“Honey, you ain’t seen cold.” Hoarse, but definitely not a him. Woman with an Australian accent. “Graeter said you were supposed to come tomorrow. Lucky for you, the pilot radioed about an incoming.”

“Graeter?”

“Station manager. Think you can grab maybe one bag?” Hallie heard condescension, irritation, or a combination. She dumped both duffels onto the orange cargo sled.

“So why are you here? Nobody ever comes early for winterover,” the woman said. She sounded angry, though Hallie was hard-pressed to understand why. Chronic ire of the short? But then, going from cozy station to one hundred below for some clueless stranger could

do it, too. A coughing fit left the woman gasping. She straightened, breathed in gingerly.