Full Moon

FULL MOON

UK TITLE: THERE WAS A DOOR

The American Weekly

, Oct 28, 1934-Jan 27, 1935

First US book edition: D. Appleton-Century, New York, 1935

First UK book edition: Hutchinson & Co., London, 1935

as “There Was a Door”

Reprinted in

Famous Fantastic Mysteries

, Feb 1953

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

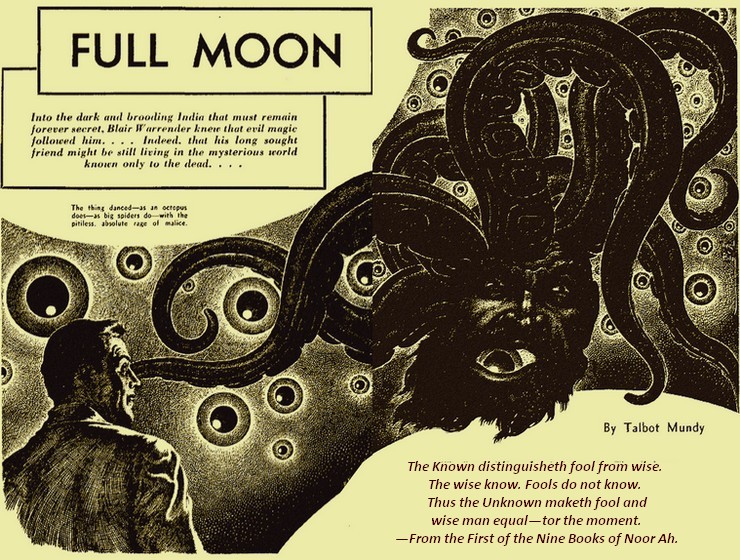

- Illustration 1.

Title graphic - Illustration 2.

The men around the tiger’s carcass resembled ghouls at a graveyard feast of

flesh. - Illustration 3.

They golden objects were as weirdly-shaped as the most fantastic designs of

a Futurist sculptor - Illustration 4.

The giantess stared forth, awesome, splendid - Illustrations 5 and 6.

5. Cover of

Famous Fantastic Mysteries

, Feb 1953, with reprint of

“Full

Moon”

6. Cover of 1953 edition, Royal Books, New York (“Full Moon” in one volume

with

Charles Ray Willeford’s “High Priest of California”)

BOMBAY sweltered. The police commissioner’s dim-lit library

was stifling in spite of electric fans. The night’s humidity, the length of a

garden, and two streets deadened the clang of tramcars; but there was a

rumbling undertone of indrawn rancor. There had been a three-day pause,

brooding between riots; passion, momentarily exhausted, redistilled itself at

ninety in the shade. But the watch kept. Police headquarters are where the

commissioner is at the end of a telephone. He clicked back the phone on its

rest and wiped his forehead; a gray man, with a rather close-clipped gray

mustache and heavy eye-brows over his dark and deep-sunken eyes.

Blair Warrender took the chair opposite and eased his long legs under the

table. He was a much younger man, not scared of the commissioner but not

quite at ease. The commissioner was an irritating enigma—he was

sometimes genial, equally often sardonic. He expected his subordinates to

work in the dark and take the blame for accidents. He had a better than usual

record for blaming or praising the right man, but he trusted subordinates,

according to their view of it, too much or not enough.

He almost never trusted one individual with all the facts of a case. When

he called a man by his first name, it might indicate confidence, or it might

reveal familiarity that borders on contempt; there was no knowing which. But

no one, least of all Blair Warrender, doubted his ability or dreamed of

disobeying his orders.

There was a rather new scar on his chin, but nothing very noticeable about

Blair Warrender except his eyes. They smoldered. They made some women hate

him at sight. Other, wiser women, recognized controlled and consequently

deadly anger; some took sporting chances with it. Wiser women yet sought his

friendship, dangerous in one sense though it might be. Men found him easy to

work with, if rather exacting. He was very neat in a new uniform that he

could ill afford: his other one had been torn off his back by Hindus. In the

course of routine duty he had saved some of them from being scragged by

Moslems, and they had therefore accused him of racial prejudices along with

more unmentionable faults: but he was used to that and exasperatingly

unresentful.

The table was near one end of the room, where the shaded electric light

made the Bokhara hanging look like a blood-stained arras. At the other end of

the room, near the door, stood a turbaned servant who had rather Mongolian

eyes: when the commissioner, with a cigar in one side of his mouth, grumbled

indistinctly and in a low voice that it was the hottest night in ten years,

the servant examined the switch of the electric fan. So the commissioner

pitched his voice still lower.

“Read this.”

He handed Blair Warrender a London daily paper ten days old, blue-penciled

at a headline in heavy type:

class=“headline” INDIA: BRITISH OFFICER MYSTERIOUSLY MISSING. RUMORED

VICTIM OF TERRORISTS. OFFICIAL SILENCE.

Blair Warrender read the paragraph—frowned— passed the paper

back.

“Frensham,” he said, “has been missing for months. According to the League

of Nations report about a hundred thousand people vanish every year without

trace. The mystery is that the papers didn’t learn of this sooner. I suppose

this means trouble.”

“For you, yes. You find Frensham.” The commissioner folded the newspaper,

laid it on some other documents and slipped an elastic band over the lot.

Then he handed a file of reports across the table. “I need you like the devil

here in Bombay, but”—he paused perceptibly, with his eyes on the

servant over by the door—“you are to take this case and find Frensham

dead or alive.”

Blair Warrender scowled over the file, turning the papers and idly

refreshing memory.

“Nothing new here, sir. We knew all this before Frensham was three days

massing? On leave in Rajputana—vanished—trunk in his bedroom, at

the Kaiser-i-Hind Hotel at Mount Abu found cut open and looted of unknown

contents—one servant, said to be deaf-and dumb, also missing—the

other servant paid off. sent home and knows nothing. Private affairs

apparently in order—no money trouble—no debts—no known

enemies—health good—no probable reason for suicide. Nothing new

in that file.”

“Did you notice the date?”

“The eleventh.”

The commissioner pushed a calendar across the table. “Notice anything

else?”

“No. The calendar says full moon on the fifteenth, but what of it?”

“Bear that in mind. Leaving Mount Abu on horseback, tiding leisurely, a

man might reach Gaglajung in three days. There is an unconfirmed and

unreliable report that a man who might be David Frensham was seen on foot,

not far from Gaglajung, on the late afternoon of the fourteenth.”

“Why should he go there?”

“That’s for you to find out. Frensham’s friend at Doongar, which is near

Gaglajung, is a Mohammedan named Abdurrahman Khan. He’s a quite unimpeachable

gentleman, aged seventy—ex-rissaldar of irregular horse —three

medals—five bars—

persona grata

—old and innocuous. He

might have supplied a horse or two; he has them. Night, near the full of the

moon, in Rajputana, is the best time to travel, and horses that reached Mount

Abu by night and left the same night might not be noticed.

“Abdurrahman Khan may have liked Frensham as much as I did. He’d be

capable of doing what he was asked, and saying nothing. Men of his type,

expecting to die soon, have a way of letting secrets die with them. You won’t

get much out of him, but you may get something, if you’re careful and don’t

ask questions.”

Warrender lit a cigarette and glanced in a mirror to see why the

commissioner kept watching the servant, but the glance told him nothing.

“Abdurrahman Khan may already have been questioned,” he said.

The commissioner nodded. “Yes. If so, he’ll tell nothing at all.” He took

his eyes off the servant at last and looked straight at Blair. “But there are

some scattered facts worth noting. For instance, Frensham had a photograph of

Wu Tu among his private papers.”

Blair scowled at that. “Who hasn’t? Wu Tu advertises herself like a

film-star.”

“Know what her name means?”

“Yes—Chinese for ‘Five Poisons.’”

“Right. Wu Tu may have murdered Frensham.”

Blair Warrender held his tongue. He had suggested investigating Wu Tu

months ago, but no one who was even half-wise reminded the commissioner about

advice that he had seen fit not to take.

“David Frensham,” the commissioner continued, “has been my intimate

personal friend for going on thirty years. His wife died more than twenty

years ago. Aside from his personal kindliness, he was a charming lunatic or a

great genius, either or perhaps both. An omnivorous reader—student of

archaeology and ancient languages—mathematician— philosopher. He

used to read Charles Fort’s books. Nothing delighted him more than to prove

Charles Fort right and everybody else wrong. Do you know Fort’s books?”

“Yes. His daughter Henrietta lent them to me.”

“That’s another clue. Keep that also in mind. So far, you’ve the new moon

on the fifteenth—Gaglajung, where a charcoal-burner said he saw a man

who might be Frensham— Abdurrahman Khan, who may have provided

horses—Wu Tu’s photograph—Charles Fort’s books and Frensham’s

known delight in Indian magic. That’s stuff that no soldier should tackle,

although soldiers are the ones who seem most interested. It gets them a ‘rep’

for being unreliable and shuts them off from promotion. Headquarters were

always glad to let Frensham wander off investigating one thing or another. As

an Engineer officer he had plenty of opportunities for that, and he did some

decent Intelligence work. But he couldn’t let magic alone. Secret Service

File FF is half-choked with his reports on that stuff.”

Blair Warrender smiled. “Do you believe in magic?”

“I am not saying what I believe. That file is raw material for scientific

study, I don’t mind telling you. It contains stories from men returned from

Himalayan expeditions that would make your hair stand on end. Frensham

believed magic is the crumbled remnants of an ancient science. That’s a clue

to his disappearance.”

“As you say, sir. I know nothing about magic.”

“Nor I, except what David Frensham told me.” The commissioner dropped his

voice even lower. “But don’t forget that some people think they do know. I’m

about to introduce you to a man who thinks he does; whether he does or

doesn’t is beside the point. Study him.”

His eyes were again on the servant, but his right hand went into a steel

box on the table. He groped in it among docketed papers. Deliberately,

slowly, he produced what looked like a block of gold, seven or eight inches

long by about half that breadth and depth.

“Look at it,” he said. “Take hold of it.” It was heavy. Blair weighed it

in both hands —examined it narrowly, thumbing a corner where a very

small piece had been sawn or chipped off.

“I did that,” said the commissioner. “Had it analyzed. Almost pure gold.

Something less than one half of one per cent of an unknown alloy that makes

it harder than cast iron. But it seems to become permanently soft, like

ordinary gold, after being melted two or three times.”

Blair Warrender’s eyes betrayed a vague excitement.

“Pure gold?” he said. “No, not heavy enough.”

“Shake it.”

The thing was hollow. He could feel but not hear movement of something

loose inside it.

“Well?” he demanded. It made him angry to have traps set for his

curiosity; he was not a baby being set conundrums. The commissioner noticed

that. He seemed amused. He spoke almost absent-mindedly.