Full Tilt (22 page)

Authors: Dervla Murphy

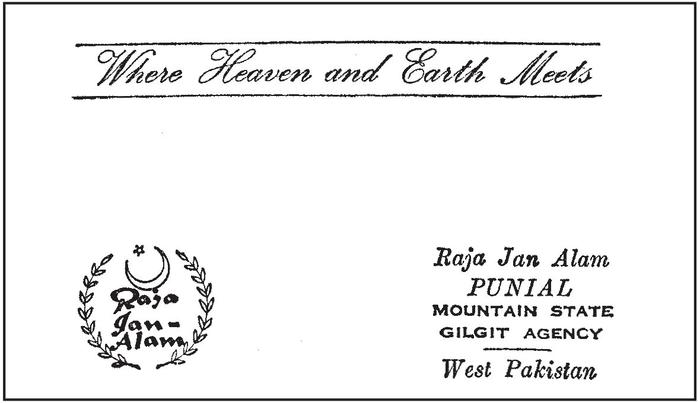

After dinner tonight the Raja again urged me to accept his offer of a little farm here and settle down for life ‘where Heaven and earth meets’. He had already questioned me very closely about my family and financial affairs (as do all Asians, quite uninhibitedly) and he said this evening that I’d be far better off farming in Punial rather than living on fresh air in Ireland! I thanked him very much and explained that I couldn’t be happy permanently exiled from Ireland, just as he couldn’t if exiled from Punial – but he wasn’t convinced. As his card so clearly shows, he thinks Punial the best place in the world and he also thinks farming the only occupation fit for any self-respecting person, all other ways of earning a living being regarded as debased, if not actually immoral.

I really must uproot from here in the early hours of tomorrow morning and get to Gilgit by the afternoon – but it is difficult! I went

for another walk before dinner, at river level this time, right down the valley; it runs due east–west, so when I was returning the last, long shadows were before me, and the few frail scraps of cloud overhead were golden, the leaves were showing silver in the westerly breeze and the air was laden with the evening scent of shrubs and herbs. I ate some wild raspberries – tiny and tart and very refreshing. I’ve also discovered that

un

ripe apricots are one of the best of all thirst quenchers. Now early to bed.

I left my Raja, who was looking disproportionately devastated by the parting, soon after 5 a.m. His grey stallion took me to Gulapur, where the locals had got adjusted to having a cycle in their midst – the teacher told me that they had crowded around Roz daily during my absence. Half the little boys of the village were demanding to be given a ride and as there are a

lot

of little boys in every Asian village, this meant that it was 8.15 before I got away.

At the hamlet which lies halfway between Gulapur and here I was waylaid by a deputation of elders and a delightful old woman ushered me into a room absolutely devoid of furniture. There we sat on a straw mat and I was given buttermilk with salt – an honour of which I was most appreciative, salt being so precious here – and a big plate of

paratis

– very greasy, but I love them if the fat is not

too

rancid – and a pot of tea with sugar in it, which is another mark of esteem. This banquet was a joint effort by the whole community; flour, ghee, tea, sugar, salt, tea-pot and china cups all came from different homes. (Normally tea-pots are never used; the leaves and milk and water and sugar or salt are put in a flat pan and boiled up together.) I really appreciated their kindness, which was obviously meant to atone for the way they had unanimously shunned me (out of sheer

astonishment

and fear of the unknown) when we passed through before; I will never forget that reception committee. Neither will I ever forget the number of flies in that little mud house: the air was thick with them and voices had to be raised above their buzzing. The room was packed to capacity with villagers, all sitting around beaming at me, and the

girls took it in turns to sit beside me waving green willow branches to keep the flies off my person and food – a procedure which made me feel vaguely like Cleopatra!

Then, halfway between that hamlet and Gilgit, an old woman spotted me toiling uphill, dragging Roz through deep sand, so she pursued me with an apron full of the biggest and juiciest figs I’ve ever eaten; all in all this has been one of my better-fed days, reaching a grand climax with a four-course dinner at the mess tonight.

My first request on arrival here was for some anti-lice preparation; the brutes have been devouring me since that night when I shared verminous blankets with the children, and they have successfully put up a stiff resistance to countless applications of soap and water.

I’ve noticed since entering Pakistan that comparatively few people say their prayers publicly here, though the majority are Sunnis, as in Turkey and Afghanistan. At dinner tonight it became apparent that both Sunnis and Shias hate Ismailis even more than they hate each other – and that’s quite a lot. They say contemptuously that Ismailis are not

real

Muslims, and accuse them of never praying to Allah and only worshipping the Aga Khan. How true all this is I wouldn’t know.

The temperature here today is 101°and 112° at Pindi.

I’m often astounded by the odd conceptions people have about what constitutes beautiful scenery. Last night two United Nations surveyors, who have recently gone from Gilgit to Chilas by jeep, told me that the landscape was dreadfully dull and that I shouldn’t bother to cycle but should wait for the jeep which brings supplies to Chilas every Monday. Of course I didn’t believe them, knowing that the Indus Gorge couldn’t possibly be dull, but when I saw how uniquely magnificent the landscape actually is I decided that they must be completely blind.

Today’s run was a complete contrast to my ride up and down the Gilgit Valley, but was no less beautiful and even more desolate. During the whole forty-three miles I didn’t see

one

man, goat, bird, blade of

grass or any sign of life, whereas in the other valley I passed a few people and animals every day and villages were much more frequent, even if often inaccessible from my track.

This jeep road was ‘cycleable’ (slowly) for about thirty miles and I walked the rest through ankle-deep sand, which gave me the feeling that some invisible person was trying to pull Roz back all the time. We started at 4.30 a.m. and as I had missed my siesta yesterday I felt quite dopey by 11.30, but kept going till shade was found under a big rock. Then saying ‘To hell with snakes!’ I curled up on the deep, soft sand and slept soundly from 12 to 3.30. I woke to find that a strong breeze had got up, which made the air very pleasant, and after a meal of eggs and bread and apricots we set off again. The water situation was grim all day. This valley is much wider than the other and there are no streams or nullahs till you get to Juglote, while the river is always out of reach. Occasionally it’s out of sight too, as the ‘road’ goes over sand desert with only two lines of boulders to mark the route to be followed. At other times, where the track wriggles round precipices of sheer, bare rock, it’s visible 1,000 feet below, in the deep gorge it has carved through the mountains, and to be able to see and hear water you can’t possibly reach is the quintessence of torture. I had to make do on six pints when I could have used at least eighteen. On arriving at the Juglote nullah I drank twelve pints just like

that

and I’ve drunk another six since I came to the hamlet itself. But for all its hardships I wouldn’t have missed today’s journey. Nanga Parbat is directly overlooking Juglote and was visible all the afternoon, thrusting up grandly from the wild array of surrounding peaks; it’s definitely the second most impressive mountain I’ve seen, after Ararat, with Demavand a good third on my list. Lying east of the road it was a glorious spectacle at sunset, with the last golden rays pouring over the peaks to the west and being caught by the snow-laden summits of the Nanga Parbat range, whilst the Indus Gorge was already full of purple dusk and the surrounding desert was a still expanse of greyness.

The people here are reputed to be rather wild and I had trouble persuading Colonel Shah not to provide me with an escort. Finally I said, ‘Where are you going to get (

a

) another bicycle and (

b

) a

soldier who would ride and push it over the Babusar Pass?’ He saw my point, and that was that! In fact I find the locals very kind, though admittedly they are much rougher types than in the Gilgit Valley. But I sense no danger here though I’m sleeping on a charpoy by the roadside.

My eyes are going queer again from this last week of writing by the light of juniper roots. We’ll make another dawn start tomorrow, so bed now.

This is a day to go down in my personal history as having given me the toughest cycling of a lifetime, not likely ever to be surpassed, though it may be equalled tomorrow. I was up at 4 a.m. and we left Juglote at 4.30, after a meagre breakfast of dry bread and tea. Only apricots were available for my picnic lunch. I covered no more than forty-five miles between that and 5.45 p.m. but each one felt like four anywhere else and there was no time for a siesta as we were ploughing through deep sand from 8 a.m. onwards and climbing practically vertical hills, all in fierce heat. The temperature was almost up to Pindi heights because of the bare rock mountains overlooking sand-deserts devoid of plant life. What a landscape! The sheer magnitude of everything is overwhelming – the height of the mountains, the depth of the Indus gorge, the fabulous chunks of rock scattered about the desert (some are literally as big as what we in Ireland call a mountain, yet here they are simply bits of rock broken jaggedly off a nearby peak), the perfect stillness and the brutal sun; despite being half-dead by 2 p.m. it was an experience worth the exhaustion.

I’m three-quarters dead now and just waiting for some form of food before falling asleep. On yesterday’s basis the traffic was hectic today – one tribesman and one jeep. The tribesman looked terrifying – armed with a spear – but actually he was very amiable and seemed thrilled to bits when I took his photo. The jeep looked no less terrifying going up a stretch of track 800 feet above the Indus on a surface that was literally loose slabs of blasted rock. All the passengers had to get out and walk

up, otherwise even a jeep couldn’t make this gradient. Similarly, all loads had to be removed and carried up and re-loaded at the top; it’s inconceivable how even an empty vehicle can ascend these stretches: certainly the jeep is a wonderful invention.

I’m yawning so much that if no grub appears soon I’ll fall asleep where I sit – anyway I’m now too tired to feel hungry. I think the heat would have finished me today but for the fact that five nullahs appeared during the last twenty miles. Not that they made much difference to the temperature, as all were in deep clefts between mountains and there was no growth around them, but I got into them fully clothed and soaked myself for about fifteen minutes from head to boots. After another fifteen minutes I was bone dry again yet these immersions kept my temperature down somewhat. The water was just pleasantly cool, not icy as in the Gilgit Valley – otherwise I daren’t have plunged in when so over-heated. But as these nullahs are also from melting glaciers, this shows how hot the region is. Anyway heat shouldn’t be one of my worries tomorrow as surely even in June the Babusar Pass will be cool. Beyond a doubt

I

find such heat absolutely prostrating: maybe other constitutions can take it better.

I crossed one suspension bridge today and on it was a marble plaque to the memory of seven German climbers and nine Sherpa guides who were killed while attempting Nanga Parbat on 14 June 1937. The mountain itself rises on the other side of the river and there their bodies still lie. All the Germans were under thirty years old – but perhaps they were lucky; challenging Nanga Parbat is a better way to die than fighting for Nazism.

I lost my toothbrush last week when it fell into the river. Washing my teeth is the one thing I fuss about – not that they are getting much to do these days.

Still

no sign of grub! And in this hamlet (without the Prince) there aren’t even mulberries or apricots or wine: I can’t imagine what the people eat. But they’re very nice folk and I’m quite sure are doing their best to dig up something for me – I only hope they’ve not gone to the snow-line to dig up ghee!

Later

. I was wakened at 10 p.m. and served with one

chapatti

of maize flour and a one-egg omelette.

Well, I was wrong – yesterday’s effort was a cake-walk compared with today’s. In fact the only enjoyable part of today’s performance is this – sitting down to write about it after recovering (more or less) from the consequences.

We left Goner at 5.30 a.m. and arrived here at 4.30 p.m., having only covered twenty-eight miles, yet I came into the shade of this nullah in a state of total collapse, so decidedly at the end of my tether that I don’t believe I could have kept going

one

more mile. The Tahsildar here told me that when I arrived the temperature was 114° – he didn’t really have to say it! I had to walk all the way as the first twenty miles were through very deep sand, up and down very steep hills, and after that I was too dizzy from the heat to balance on Roz, even where the track was level. By 7 a.m. the sun was so hot that I was saturated through with sweat and as we only came to one nullah for wetting, cooling and refilling the water bottle, dehydration became my fear. I found shade once, under a rock, and slept very soundly from 1.40 to 2.50 p.m., although lying on sharp flints. After that the real trouble began and by 3 p.m. I was seriously worried: I had stopped sweating, which is a danger signal, and my mouth was so dry that my tongue felt like an immovable bit of stiff leather. By 3.30 I was shivering with cold, though the heat was so intense that I did not dare touch any metal part of Roz. After that I just kept going but don’t remember one bit of the road – only that the green trees of Chilas were visible in the distance. I had just enough sense left, on getting to the nullah, not to drink gallons, but to lie under a willow and take mouthfuls at a time until gradually I began to sweat again and get warm. Then I rolled into the water and lay there for a few minutes with it rushing deliciously over me, after which I was able to walk another half-mile to the Tahsildar’s house, where I drank gallons of buttermilk and salt followed by cups and cups of hot tea; but I couldn’t look at food this evening.

Chilas is only 3,000 feet above sea level and is hellishly hot even amidst all the running brooks and dense green trees and shrubs –

because it’s completely encircled by naked rock-mountains which relentlessly throw back that intolerable sun. The Tahsildar (a minor local government official) says that I must stay here tomorrow for a day’s rest before going over the Babusar and I couldn’t agree more! Not that the pass will be difficult after the last three days; once I get eight miles up (and I’ll start at 3.30 a.m.) it will be cool, and it’s heat, not gradients, that finish me off.

The horror of today’s trek really was extreme with heat visibly flowing towards me in malevolent waves off the mountainsides and the dreadful desert stench of burning sand – which still persists here – nauseating me; the terrifying dehydration of mouth and nostrils and eyes until my eyelids could barely move and a sort of staring blindness came on, with the ghastly sensation of scorching air filling my lungs, and the overpowering drug-like effect of the wild thyme and sage, that grow thickly over the last few miles, being ‘distilled’ by the sun; and above all the despair of coming round corners and over hilltops time and time again, hoping always to see water – and never seeing it. I have often thought that death by thirst must be grimmer than most deaths and now my surmise has been confirmed. The irony of it all was that all day the vast, swirling Indus flowed beside me, inaccessible. But what a magnificent valley it is! Though I could have done without this afternoon’s instalment, I wouldn’t have liked to miss this morning’s panoramas; the rough track soared up and up and up the sheer black and beige mountainsides till even the tremendous roar of the Indus was inaudible and it looked a mere bit of brown ribbon, coiling for miles in both directions between its colossal, but now dwarfed, cliffs. From these the desert swept flatly to the foot of gigantic peaks, some of them almost level with the track. Occasionally, on the other side of the river, there was an unexpected oasis, around a nullah, inhabited by Indus gold searchers. These are a brown-skinned people unlike the other tribes of the area and they are much despised by the local farming-folk, who consider that searching for gold is a menial

occupation

! (From my distance those meagre oases, as they stood out on the level ‘table’ of sand, reminded me of the little wooden trees I had as a child with my toy farm. I saw several of the ‘gold-men’ by the river’s

edge, perilously scooping and sieving in quest of that Indus gold which is supposed to be one of the best in Asia. Incidentally, a peculiar kind of precious stone is found around Punial and Gilgit – like an opal but better. I don’t know if they belonged to ancient peoples or not but all local women have at least one in their necklaces.) Sometimes the ‘

gold-men

’ cross the river by inflating two goatskins, laying planks across them and paddling over; naturally they land about ten miles downstream because of the ferociously swift current, but they rarely have an accident.