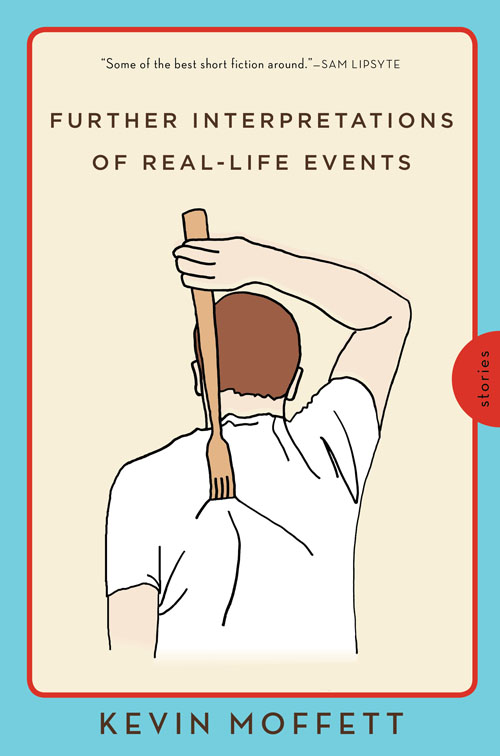

Further Interpretations of Real-Life Events

Read Further Interpretations of Real-Life Events Online

Authors: Kevin Moffett

further interpretations of real-life events

stories

kevin moffett

for ellis

further interpretations of real-life events

A

fter my father retired, he began writing trueish stories about fathers and sons. He had tried scuba diving, had tried being a dreams enthusiast, and now he'd come around to this. I was skeptical. I'd been writing my own trueish stories about fathers and sons for years, stories that weren't perfect, of course, but they were mine. Some were published in literary journals, and I'd even received a fan letter from Helen in Vermont, who liked the part in one of my stories where the father made the boy scratch his stepmom's back. Helen in Vermont said she found the story “enjoyable” but kind of “depressing.”

The scene with the stepmom was an interpretation of an actual event. When I was ten years old, my mother died. My father and I lived alone for five years, until he married Lara, a kind woman with a big laugh. He met her at a dreams conference. I liked her well enough in real life but not in the story. In the story, “End of Summer,” I resented Lara (changed to “Laura”) for marrying my father so soon after my mother died (changed to five months).

“You used to scratch your ma's back all the time,” my father says in the final scene. “Why don't you ever scratch Laura's?”

Laura sits next to me, shucking peas into a bucket. The pressure builds. “If you don't scratch Laura's back,” my father says, “you can forget Christmas!”

So I scratch her back. It sounds silly now, but by the end of the story, Christmas stands in for other things. It isn't just Christmas anymore.

The scene was inspired by the time my father and Lara went to Mexico City (while I was marauded by bullies and blackflies at oboe camp) and brought me home a souvenir. A tin handicraft? you guess. A selection of cactus-fruit candy? No. A wooden back-scratcher with extended handle for maximum self-gratification. What's worse,

Te quiero

was embossed on the handle. Which I translated at the time to mean “I love me.” (I was off by one word.)

“Try it,” my father said. His tan had a yolky tint and he wore a T-shirt with

PROPERTY OF MEXICO

on the back. It was the sort of shirt you could find anywhere.

I hiked my arm over my head and raked the back-scratcher north and south along my vertebrae. “Works,” I said.

“He spent all week searching for something for you,” Lara said. “He even tried to haggle at the

mercado

. It was cute.”

“There isn't much for a boy like you in Mexico,” my father said. “The man who sold me the back-scratcher, though, told me a story. All the men who left to fight during the revolution took their wives with them. They wanted to remember more . . .”

I couldn't listen. I tried to, I pretended to, nodding and going

hmm

when he said

Pancho Villa

, and

wow

when he said

gunfire

, and then

some story

when it was over. I excused myself, sprinted upstairs to my bedroom, slammed my door, and snapped that sorry back-scratcher over my knee like kindling.

A boy like me!

Y

ou'll never earn a living writing stories, not if you're any good at it. My mentor Harry Hodgett told me that. I must've been doing something right, because I had yet to receive a dime for my work. I day-labored at the community college teaching Prep Writing, a class for students without the necessary skills for Beginning Writing. I also taught Prep Prep Writing, for those without the skills for Prep Writing. Imagine the most abject students on earth, kids who, when you ask them to name a verb, stare like you just asked them to cluck out a polka with armpit farts.

Literary journals paid with contributors' copies and subscriptions, which was nice, because when your story was published, you at least knew that everyone else in the issue would read your work. (Though, truth be told, I never did.) This was how I came to receive the autumn issue of

Vesper

âI'd been published in the spring issue. It sat on my coffee table until a few days after its arrival, when I returned home to find Carrie on my living-room sofa, reading it. “Shh,” she said.

I'd just come back from teaching, dispirited as usual after Shandra Jones in Prep Prep Writing told a classmate to “eat my drippins.” A bomb I defused with clumsy silence, comma time!, early dismissal.

“I didn't say anything,” I said.

“Shh,” she said again.

An aside: I'd like to have kept Carrie out of this, because I haven't figured out how to write about her. She's tall with short brown hair and brown eyes and she wears clothes andâsee? I could be describing anybody. Carrie's lovely, her face is a nest for my dreams. You need distance from your subject matter. You need to approach it with the icy, lucid eye of a surgeon. I also can't write about my mother. Whenever I try, I feel like I'm attempting kidney transplants with a can opener and a handful of rubber bands.

“Amazing,” she said, closing the journal. “Sad and honest and free of easy meanness. It's like the story was unfolding as I read it. That bit in the motel: wow. How come you never showed me this? It's a breakthrough.”

She stood and hugged me. She smelled like bath beads. I was jealous of the person, whoever it was, who had effected this reaction in her: Carrie, whom I met in Hodgett's class, usually read my stories with barely concealed impatience.

“Breakthrough, huh?” I said casually (desperately). “Who wrote it?”

She leaned in and kissed me. “You did.”

I picked up the journal to make sure it wasn't the spring issue, which featured “The Longest Day of the Year,” part two of my summer trilogy. It's about a boy and his father (I know, I know) driving home, arguing about the record player the father refuses to buy the boy, even though the boy totally needs it since his current one ruined two of his Yes albums, including the impossible-to-find

Time and a Word

, andâ

boom

âthey hit a deer. The stakes suddenly shift.

I turned to the contributors' notes.

F

REDERICK

M

OXLEY

is a retired statistics professor living in Vero Beach, Florida. In his spare time he is a dreams enthusiast. This is his first published story.

“My dad!” I screamed. “He stole my name and turned me into a dreams enthusiast!”

“Your

dad

wrote this?”

“And turned me into a goddamn dreams enthusiast! Everyone'll think I've gone soft and stupid!”

“I don't think anyone really reads this journal,” Carrie said. “No offense. And isn't he Frederick Moxley, too?”

“Fred! He goes by Fred. I go by Frederick. Ever since third grade, when there were two Freds in my class.” I flipped the pages, found the story, “Mile Zero,” and read the first sentence:

As a boy, I always dreamed of flight.

That makes two of us, I thought. To the circus, to Tibet, to live with a nice family of Moonies. I felt tendrils of bile beanstalking up my throat. “What's he trying to do?”

“Read it,” Carrie said. “I think he makes it clear what he's trying to do.”

If the story was awful, I could easily have endured it, I realize now. I could've called him and said if he insists on writing elderly squibs, please just use a pseudonym. Let the Moxley interested in truth and beauty, etc., publish under his real name. But the story wasn't awful. Not by a long shot. Yes, it broke two of Hodgett's six laws of story-writing (Never dramatize a dream; Never use more than one exclamation point per story), but he'd managed some genuine insight. Also he fictionalized real-life events in surprising ways. I recognized one particular detail from after Mom died. We moved the following year, because my father never liked our house's floor plan. That's what I'd thought, at least. Too cramped, he always said; wherever you turned, a wall or closet blocked your path. In the story, though, the characters move because the father can't disassociate the house from his wife. Her presence is everywhere: in the bedroom, the bathroom, in the silverware pattern, the flowering jacaranda in the backyard.

She used to trim purple blooms from the tree and scatter them around the house, on bookshelves, on the dining-room table

,

he wrote.

It seemed a perfectly attuned response to the natural world, a way of inviting the outside inside.

I remembered those blooms. I remembered how the house smelled with her in it, though I couldn't name the smell. I recalled her presence, vast ineffable thing.

I finished reading in the bath. I was no longer angry. I was a little jealous. Mostly I was sad. The story, which showed father and son failing to connect again and again, ends in a motel room in Big Pine Key (we used to go there in December), the father watching a cop show on TV while the boy sleeps. He's having a bad dream, the father can tell by the way his face winces and frowns. The father lies down next to him, hesitant to wake him up, and tries to imagine what he's dreaming about.

Don't wake up

, the father tells him.

Nothing in your sleep can hurt you

.

The boy was probably dreaming of a helicopter losing altitude. It was a recurring nightmare of mine after Mom died. I'd be cutting through the sky, past my house, past the hospital, when suddenly the control panel starts beeping and the helicopter spins down, down. My body fills with air as I yank the joystick. The noise is the worst. Like a monster oncoming bee. My head buzzes long after I wake up, shower, and sit down to breakfast. My father, who's just begun enthusing about dreams, a hobby that even then I found ridiculous, asks what I dreamed about.

“Well,” I say between spoonfuls of cereal. “I'm in a blueâno, no, a golden suit. And all of a sudden I'm swimming in an enormous fishbowl in a pet store filled with eager customers. And the thing is, they all look like you. The other thing is, I love it. I want to stay in the fishbowl forever. Any idea what that means?”

“Finish your breakfast,” he says, eyes downcast.

I'd like to add a part where I say

just kidding

, then tell him my dream. He could decide it's about anxiety, or fear. Even better: he could just backhand me. I could walk around with a handprint on my face. It could go from red to purple to brownish blue, poetic-like. Instead, we sulked. It happened again and again, until mornings grew as joyless and choreographed as the interactions of people who worked among deafening machines.

In the bathroom, I dried myself off and wrapped a towel around my waist. I found Carrie in the kitchen eating oyster crackers. “So?” she said.

Her expression was so beseeching, such a lidless empty jug.

I tossed the journal onto the table. “Awful,” I said. “Sentimental, boring. I don't know. Maybe I'm just biased against bad writing.”

“And maybe,” she said, “you're just jealous of good writing.” She dusted crumbs from her blouse. “I know it's good, you know it's good. You aren't going anywhere till you admit that.”

“And where am I trying to go?”

She regarded me with a look I recalled from Hodgett's class. Bemused amusement. The first day, while Hodgett asked each of us to name our favorite book, then explained why we were wrong, I was daydreaming about this girl in a white V-neck reading my work and timidly approaching me afterward to ask,

What did the father's broken watch represent?

and me saying

futility

, or

despair

, and then maybe kissing her. She turned out to be the toughest reader in class, far tougher than Hodgett, who was usually content to make vague pronouncements about

patterning

and

the octane of the epiphany

. Carrie was cold and smart and meticulous. She crawled inside your story with a flashlight and blew out all your candles. She said of one of my early pieces, “On what planet do people actually talk to each other like this?” And: “Does this character do anything but shuck peas?”

I knew she was right about my father's story. But I didn't want to talk about it anymore. So I unfastened my towel and let it drop to the floor. “Uh-oh,” I said. “What do you think of this plot device?”

She looked at me, down, up, down. “We're not doing anything until you admit your father wrote a good story.”

“

Good?

What's that even mean? Like, can it fetch and speak and sit?”

“Good,” Carrie repeated. “It's executed as vigorously as it's conceived. It isn't false or pretentious. It doesn't jerk the reader around to no effect. It lives by its own logic. It's poignant without trying too hard.”

I looked down at my naked torso. At some point during her litany, I seemed to have developed an erection. My penis looked all eager, as if it wanted to join the discussion, and unnecessary. “In that case,” I said, “I guess he wrote one good story. Do I have to be happy about it?”

“Now I want you to call him and tell him how much you like it.”

I picked up the towel, refastened it, and started toward the living room.

“I'm just joking,” she said. “You can call him later.”

Dejected, I followed Carrie to my room. She won, she always won. I didn't even feel like having sex anymore. My room smelled like the bottom of a pond, like a turtle's moistly rotting cavity. She lay on my bed, still talking about my father's story. “I love that little boy in the motel room,” she said, kissing me, taking off her shirt. “I love how he's still frowning in his sleep.”

I

never called my father, though I told Carrie I did. I said I called and congratulated him. “What's his next project?” she asked. Project! As if he was a famous architect or something. I said he's considering a number of projects, each project more poignant-without-trying-too-hard than the project before it.

He phoned a week later. I was reading my students' paragraph essays, feeling my soul wither with each word. The paragraphs were in response to a prompt: “Where do you go to be alone?” All the students, except one, went to their room to be alone. The exception was Daryl Ellington, who went to his rom.