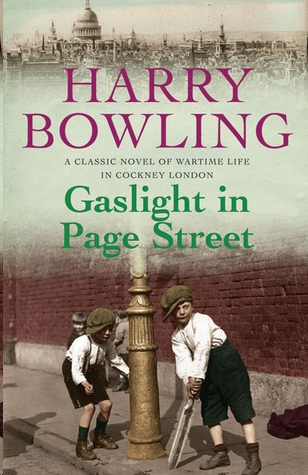

Gaslight in Page Street

Read Gaslight in Page Street Online

Authors: Harry Bowling

Copyright © 1991 Harry Bowling

The right of Harry Bowling to be identified as the Author of

the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication

may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by

any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or,

in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms

of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2010

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7553 8157 9

This Ebook produced by Jouve Digitalisations des Informations

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.headline.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Table of Contents

Harry Bowling was born in Bermondsey, London, and left school at fourteen to supplement the family income as an office boy in a riverside provisions’ merchant. He was called up for National Service in the 1950s. Before becoming a writer, he was variously employed as a lorry driver, milkman, meat cutter, carpenter and decorator, and community worker. He lived with his wife and family, dividing his time between Lancashire and Deptford. We at Headline are sorry to say that THE WHISPERING YEARS was Harry Bowling’s last novel, as he very sadly died in February 1999. We worked with him for over ten years, ever since the publication of his first novel, CONNER STREET’S WAR, and we miss him enormously, as do his many, many fans around the world.

The Harry Bowling Prize was set up in memory of Harry to encourage new, unpublished fiction and is sponsored by Headline. Click on

www.harrybowlingprize.net

for more information.

To Shirley, in loving memory

Prologue

All day long the November fog had swirled through the Bermondsey backstreets, but now that the factories and wharves had closed the fog thickened, spreading its dampness over the quiet cobbled lanes and alleyways. Only the occasional clatter of iron wheels and the sharp clip of horses’ hooves interrupted the quietness as hansom cabs moved slowly along the main thoroughfares. The drivers huddled down in the high seats, heavily wrapped in stiff blankets against the biting cold, gripping the clammy leather reins with gloved hands as they plied for hire. The tired horses held their heads low, their nostrils flaring and puffing out clouds of white breath into the poisonous fumes.

Behind the main thoroughfares a warren of backstreets, lanes and alleyways spread out around gloomy factories and railway arches and stretched down to the riverside, where wharves and warehouses towered above the ramshackle houses and dilapidated hovels. Smoke from coke fires belched out from cracked and leaning chimneys and the fog became laden with soot dust and heavy with sulphur gases. Hardly ever was the sound of hansom cabs heard in the maze of Bermondsey backstreets during the cold winter months, and whenever a cabbie brought a fare to one of the riverside pubs he always sought the quickest way back to the lighted main roads. There was no trade to be had in these menacing streets on such nights, and rarely did folk venture from their homes except to visit the nearest pub or inn, especially when the fog was lying heavy.

Straddling the backstreets were the railway arches of the London to Brighton Railway and beneath the lofty archways a gathering of vagrants, waifs and strays spent their nights, huddled around low burning fires for warmth. Sometimes there was food to eat, when someone produced a loaf of bread which had been begged for or stolen, and it was sliced and toasted over the crackling flames, sometimes there were a few root vegetables and bacon bones which were boiled in a tin can and made into a thin broth; but often there was nothing to be had and the ragged groups slept fitfully, their bellies rumbling with hunger and their malnourished bodies shivering and twitching beneath filthy-smelling sacks which had been begged from the tanneries or the Borough Market.

One bitterly cold November night, William Tanner sat over a low fire, wiping a rusty-bladed knife on his ragged coat sleeve. Facing him George Galloway watched with amusement as his young friend struggled to halve the turnip. The railway arch that they occupied faced a fellmonger’s yard and the putrid smell of animal skins filled the cavern and made it undesirable as a place to shelter, even to the many desperate characters who roamed the area. For that very reason the two lads picked the spot to bed down for the night when their finances did not stretch to paying for a bed at one of the doss-houses. Usually there was enough wood to keep a fire in all night and no one would intrude on their privacy and attempt to steal the boots from their feet while they slept. At first the stench from the fellmonger’s yard made the two lads feel sick but after a time they hardly noticed it, and they became used to the sound of rats scratching and the constant drip as rainwater leaked down from the roof and dropped from the fungus-covered walls.

William passed one half of the turnip to George and grinned widely as his friend bit on the hard vegetable and spat a mouthful into the fire.

‘It’s bloody ’ard as iron, Will, an’ it tastes ’orrible,’ the elder lad said, throwing his half against the wall.

William shrugged his shoulders and bit on his half. ‘I couldn’t get anyfing else,’ he said. ‘That copper in the market was on ter me soon as I showed me face.’

George threw a piece of wood on to the fire and held his hands out to the flames. He was a tall lad, with a round face and large dark eyes, and a mop of matted, dark curly hair which hung over his ears and down to his shabby coat collar. At fourteen, George was becoming restless. He had attended a ragged school and learned to read and write before his street trader father dragged him away from his lessons and put him to work in a tannery. At first George had been happy but his father’s increasingly heavy drinking and brutality made the lad determined to leave home and fend for himself. Now, after two years of living on the streets, he felt it was time he started to make something of himself. George had experienced factory life and had seen how bowed and subservient the older workers had become. He had walked out of his job at the tannery and did not return home, vowing there and then that he would not end up like the others.

William Tanner sat staring into the fire, his tired eyes watering from the wood-smoke. He was twelve years old, a slightly built lad of fair complexion. His eyes were pale blue, almost grey, and his blond hair hung about his thin face. Like George he had never known his mother. She had died when he was a baby. Of his infancy he could only vaguely remember stern faces and the smell of starched linen when he was tended to. His more vivid memories were of being put to bed while it was still daylight and of having to clean and scrub out his attic room with carbolic soap and cold water. He had other memories which were frightening. There was a thin reed cane which his father had kept behind a picture in the parlour. Although it had never been used on him, the sight of that device for inflicting pain had been enough to frighten him into obedience.

When his father lay dying of typhoid in a riverside hovel, William had been taken to live with an aunt and there taught to read and write. The woman made sure he was properly dressed and fed but the home lacked love, and when his aunt took up with a local publican William became an unwanted liability. Like his friend George he began to feel the weight of a leather belt, and after one particularly severe beating William ran away from home. He had stumbled into a railway arch, half-frozen and with hunger pains gnawing at his stomach, and had been allowed to share a warm fire and a hunk of dry and mouldy bread with a group of young lads. Their leader was George Galloway and from that night William and George became firm friends. Now, as the fire burned bright, George was setting out his plans. The younger lad sat tight-lipped, fearful of what might happen should things go wrong.

‘Listen to me, Will,’ George was saying, ‘yer gotta be ’ard. Nobody’s gonna come up an’ give yer money fer nuffink. It’s dog eat dog when yer up against it. All yer ’ave ter do is foller me. We’ll roll the ole geezer an’ be orf before ’e knows what’s ’appened. I’ve cased the place an’ ’e comes out the same time every night. If all goes well, we’ll ’ave a nice few bob. Yer gotta ’ave the shekels ter get started, Will. One day I’m gonna ’ave me own business. I’m gonna wear smart clothes an’ ’ave people lookin’ up ter me. “There goes George Galloway. ’E’s one o’ the nobs,” they’ll say.’

William nodded, disturbed by the wild look in the large dark eyes that stared out at him from across the fire.

The fog had lifted a little during the morning, but now it threatened to return as night closed in. From their vantage post in a shuttered shop’s doorway the two lads watched the comings and goings at the little pub in the Old Kent Road. William made sure there was no more pork crackling left in his piece of greasy newspaper then he screwed it up and threw it into the gutter, wiping his hands down his filthy, holed jumper. He shivered from the cold and glanced at George, who was breathing on his cupped hands. ‘P’raps ’e ain’t there,’ he said, trying to inject a note of disappointment into his voice.