Generation X (22 page)

bear it?" I hear a click

click as she lights one of

Armand's pilfered So-branies. "Yes. Tobias.

Well well. What a case."

A long inhale. Silence.

Exhale. I probe: "When

did you finally see him?"

"Today. Can you be-lieve it? Five

days

after Christmas. Unbelievable. I'd made all these plans to meet before, but he kept breaking them, the knob. Finally we were going to meet down in Soho for lunch, in spite of the fact that I felt like a pig-bag after partying with Allan and his buddies the night before. I even managed to arrive down in Soho early—only to discover that the restaurant had closed down. Bloody condos, they're ruining everything. You wouldn't believe Soho now, Andy. It's like a Disney theme park, except with better haircuts and souvenirs. Everyone has an

IQ of 110 but lords it up like it's 140 and every second person on the street is Japanese and carrying around Andy Warhol and Roy Lichten-stein prints t hat are worth their weight in uranium. And everyone looks s o p l e a s e d w i t h t h e m s e l v e s . " "But what about Tobias?"

"Yeah yeah yeah. So I'm early. And it is

c-o-l-d

out, Andy. Shocking cold; break-your-ears-off cold, and so I have to spend longer than normal in stores looking at junk I'd never give one nanosecond's worth of time to normally—all just to stay warm. So anyhow, I'm in this one shop, when who should I see across the street coming out of the Mary Boone Gallery but Tobias and this really sleek looking old woman. Well, not

too

old, but beaky, and she was wearing half the Canadian national output of furs.

She'd make a better looking man than a woman. You know,

that

sort of looks. And after looking at her a bit more, I realized from her looks that she had to be Tobias's mother, and the fact that they were arguing loaned credence to this theory. She reminds me of something Elvissa used to say, that if one member of a couple is too striking looking, then they should hope to have a boy rather than a girl because the girl will just end up looking like a curiosity rather than a beauty. So Tobias's parents had

him

instead. I can see where he got his looks. I bounced over to say hi." " A n d ? "

"I think Tobias was relieved to escape from their argument. He gave me a kiss that practically froze our lips together, it was that cold out, and then he swung me around to meet this woman, saying, 'Claire, this is my mother, E/ena.' Imagine pronouncing your mother's name to someone like it was a joke. Such rudeness.

"Anyway,

Elena

was hardly the same woman who danced the samba carrying a pitcher of lemonade in Washington, D.C., long ago. She

looked like she'd been heavily shrinkwrapped since then; I could sense a handful of pill vials chattering away in her handbag. The first thing she says to me is 'My, how

healthy

you look. So tanned.' Not even a hello. She had a civil enough manner, but I think she was using her talking-to-a-shop-clerk voice.

"When I told Tobias that the restaurant we were going to go to was closed, she offered to take us up to 'her restaurant' for lunch uptown. I thought that was sweet, but Tobias was hesitant, not that it mattered, since Elena overrode him. I don't think he ever lets his mother see the p e o p l e i n h i s l i f e , a n d s h e w a s j u s t c u r i o u s .

"So off we went to Broadway, the two of them toasty warm in their furs (Tobias was wearing a fur—what a dink.) while me and my bones

were clattering away in mere quilted cotton. Elena was telling me about her art collection ('I

live

for art') while we were toddling through this broken backdrop of carbonized buildings that smelled salty-fishy like caviar, grown men with ponytails wearing Kenzo, and mentally ill home-less people with AIDS being ignored by just about everybody."

"What restaurant did you go to?"

"We cabbed. I forget the name: up in the east sixties.

Trop chic,

though. Everything is

très trop chic

these days: lace and candles and dwarf forced narcissi and cut glass. It smelled lovely, like powdered sugar, and they simply

fawned

over Elena. We got a banquette booth, and the menus were written in chalk on an easeled board, the way I

like because it makes the space so cozy. But what was curious was the way the waiter faced the menu board only toward me and Tobias. But

when I went to move it, Tobias said, 'Don't bother. Elena's allergic to all known food groups. The only thing she eats here is seasoned millet and rainwater they bring down from Vermont in a zinc can.'

"I laughed at this but stopped really quickly when Elena made a face that told me this was, in fact, correct. Then the waiter came to tell her she had a phone call and she disappeared for the whole meal.

"Oh—for what it's worth, Tobias says hello," Claire says, lighting another cigarette.

"Gee. How thoughtful."

"Alright, alright. Sarcasm noted. It may be one in the morning here, but I'm not missing things

yet.

Where was I? Right—Tobias and I are alone for the first time. So do I ask him what's on my mind? About why he ditched me in Palm Springs or where our relationship is going?

Of course not.

I sat there and babbled and ate the food, which, I must say, was truly delicious: a celery root salad remoulade and John Dory fish in Pernod sauce.

Yum.

"The meal actually went quickly. Before I knew it, Elena returned and

zoom:

we're out of the restaurant,

zoom:

I got a peck-peck on the cheeks, and then

zoom:

she was in a cab off toward Lexington Avenue.

No wonder Tobias is so rude. Look at his

training.

"So we were out on the curb and there was a vacuum of activity.

I think the last thing either of us wanted then was to talk. We drifted up Fifth Avenue to the Met, which was lovely and warm inside, all full

of museum echoes and well-dressed children. But Tobias had to wreck whatever mood there may have been when he made this great big scene at the coat check stand, telling the poor woman there to put his coat out back so the animal rights activists couldn't splat it with a paint bomb.

After that we slipped into the Egyptian statue area. God, those people were teeny weeny.

"Am I talking too long?" "No. It's

Armand's money, anyway."

"Okay. The

point

of all this is that finally, in front of the Coptic pottery shards, with the two of us just feeling so futile pretending there was something between us when we both knew there was nothing, he

decided to tell me what's on his mind—Andy, hang on a second. I'm

starving. Let me go raid the fridge."

"Right now? This is the best part—" But Claire has plonked down the receiver. I take advantage of her disappearance to remove my travel-rumpled jacket and to pour a glass of water, allowing the water in the tap to run for fifteen seconds to displace the stale water in the pipes. I then turn on a lamp and sit comfortably in a sofa with my legs on the ottoman.

"I'm back," says Claire, "with some lovely cheesecake. Are you going to help Dag tend bar at Bunny Hollander's party tomorrow night?"

(What party?) "What party?"

"I guess Dag hasn't told you yet."

"Claire, what did Tobias say?"

I hear her take in a breath. "He told me part of the truth, at least.

He said he knew the only reason I liked him was for his looks and that there was no point in my denying it. (Not that I

tried.)

He said he knows that his looks are the only thing lovable about him and so that he might as well use them. Isn't that sad?"

I mumble agreement, but I think about what Dag had said last

week, that Tobias had some other, questionable reason for seeing

Claire—for crossing mountains when he could have had anyone. That,

to me, is a more important confession. Claire reads my mind:

"But the using wasn't just one way. He said that my main attraction for him was his conviction that I knew a secret about life—some magic insight I had that gave me the strength to quit everyday existence. He said he was curious about the lives you, Dag, and I have built here on the fringe out in California. And he wanted to get my secret for

himself—for an escape he hoped to make —except that he realized by

listening to us talk that there was no way he'd ever really do it. He'd never have the guts to live up to complete freedom. The lack of rules would terrify him. /

don't know.

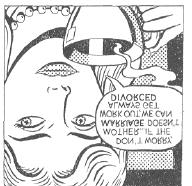

It sounded like unconvincing horseshit t o m e . I t s o u n d e d a b i t

t o o p a t ,

l i k e h e ' d b e e n c o a c h e d . W o u l d

y o u

believe it?"

Of course I wouldn't believe a word of it, but I abstain from giving an opinion. "I'll stay out of that. But at least it ended cleanly—no messy afterbirth . . . "

"Cleanly?

Hey, as we were leaving the gallery and heading up Fifth Avenue, we even did the

let's-still-be-friends

thing. Talk about

pain free.

But it was when we were both walking and freezing and thinking of how w e ' d b o t h g o t t e n o f f t h e h o o k s o e a s i l y t h a t I f o u n d t h e s t i c k .

"It was a Y-shaped tree branch that the parks people had dropped from a truck. Perfectly shaped like a water dowsing rod. Well! Talk about an object speaking to you from beyond! It just woke me up, and never in my life have I lunged so instinctively for an object as though it were intrinsically a part of me—like a leg or an arm I'd casually misplaced for twenty-seven years.

"I lurched forward, picked it up in my hands, rubbed it gently, getting bark scrapes on my black leather gloves, then grabbed onto both sides of the forks and rotated my hands inward —the classic water dows-er's pose.

"Tobias said, 'What are you doing? Put that down, you're embar-rassing me,' just as you'd expect, but I held right on to it, all the way down Fifth to Elena's in the fifties, where we were going for coffee.

"Elena's turned out to be this huge thirties Moderne co-op, white everything, with pop explosion paintings, evil little lap dogs, and a maid scratching lottery tickets in the kitchen. The whole trip. His family sure has extreme taste.

"But I could tell as we were coming through the door that the rich food from lunch and the late night before was catching up with me.

Tobias went to make a phone call in a back room while I took my jacket a n d s h o e s o f f a n d l a y d o w n o n a c o u c h t o v e g -out and watch the sun fade behind the Lipstick Building. It was like instant annihilation—that instant fuzzy bumble-bee anxiety-free afternoony exhaustion that you never get at night. Before I could even

analyze

it, I turned into furniture.

" I m u s t h a v e b e e n a s l e e p f o r h o u r s . W h e n I w o k e i t w a s d a r k o u t

and the temperature had gone down. There was an Arapaho blanket on

top of me and the glass table was covered with junk that wasn't there before: potato chip bags, magazines. . . . But none of it made any sense to me. You know how sometimes after an afternoon nap you wake up

with the shakes or anxiety? That's what happened to me. I couldn't

remember who I was or where I was or what time of year it was or

anything.

All I knew was that /

was.

I felt so wide open, so vulnerable, like a great big field that's just been harvested. So when Tobias came out from the kitchen, saying, 'Hello, Rumplestiltskin,' I had a flash of remembrance and I was so relieved that I started to bellow. Tobias came o v e r t o m e a n d s a i d , ' H e y w h a t ' s t h e m a t t e r ? D o n ' t c r y o n t h e f a b -ric . . . come here, baby." But I just grabbed his arm and hyperven-tilated. I think it confused him.

"After a minute of this, I calmed down, blew my nose on a paper towel that was lying on the coffee table, and then reached for my dowsing branch and held it to my chest. Tobias said, 'Oh, God, you're not going to fixate on the

t w i g

again, are you? Look, I

r e a l l y

didn't realize a breakup would affect you so much. Sorry.'