Gentlemen of the Road (16 page)

Read Gentlemen of the Road Online

Authors: Michael Chabon

Tags: #Fantasy, #Travel, #Modern, #Contemporary, #Adventure, #Historical

“I confess that I’m intrigued by your proposition, not to mention your audacity,” the tarkhan said. “But I feel constrained to point out that in fact it was a bow of ash wood, not horn.”

The young man blinked. The thin, pale rider coughed into his fist, and tried not quite successfully to conceal his amusement. The giant’s horse bumped as if by chance against the horse of the green-eyed young man, jarring him out of his hesitation.

“My mistake,” said the stripling.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN ON FOLLOWING THE ROAD

ON FOLLOWING THE ROAD

TO ONE’S DESTINY, WITH

THE USUAL INTRUSIONS

OF VIOLENCE AND GRACE

F

or half a day the captain of archers—a javshigar in the Army of the Khazar with fifteen years of service to the candelabrum flag—had suffered, shifting from foot to foot, pulling now at his mustache, now at the fingers of his glove, as the warrior king to whom he had sworn loyalty by oaths so ancient and binding they resisted even the power of the autumnal Disavowal haggled and pleaded for the safety of the house of Buljan with a barbarous swaggering Rus butcher whom the vicissitudes of the plunderous life had left only half a face.

Then as in ages to come it was a point of contention whether the Northmen were better endowed by their greedy and termagant gods for commerce or slaughter, but in the judgment of the captain of archers these were complementary gifts. Hour after hour the two men dickered, the bek with his wife at his side, his children squalling or staring in dumb wonder at the Rus. The Northmen sprawled along the wharf like white mountains in bloodstained tunics, encouraging Ragnar Half-Face to turn the greasy Khazar upside down by the ankles and shake him until every last dirham fell out of his pockets. Around them long trains of Buljan’s slaves staggered down from the Qomr with armloads and sacks of gold and silver plate, gemstones and ivory silks and spices and perfumed wood, making up the price of passage for Buljan and his household. The Rus rowed the booty out to their ships and then rowed back again blowing and grinning and hungry for more. The captain of archers fidgeted and coughed and rolled his eyes at his men, as if such cupidity and dishonor were an inevitable but minor aspect of the human predicament akin to sharptonguedness in a wife, but felt a hot needle of outrage sounding his belly. He prayed to his own God of Outrage, Iehovah, to send a righteous thunderbolt to strike the half-leering Rus chieftain down or, at the very least, to satisfy the bastard, and once and for all rid Khazaria of the stain of cowardice and the smell of the Northmen and of the ruinous usurper Buljan. But when the captain saw them bringing down the new elephant and felt the thrill of dismay running through all the stout Khazar archers of his company, he felt the insufficiency of prayer to the relief of grievous outrage. He settled his armored cap more firmly on his head, and cleared his throat, and with a hand on the hilt of his Damascene poniard strode heels knocking against the dock over to the side of the man who in a show of bankrupt bravery had proclaimed himself bek, and lowering his eyes, his voice clear but his manner as yet tinged with the long habit of obedience, said, “I regret, honored Buljan, that I must place you under arrest.”

At once all the Northmen got up and unsheathed their blades or spoke eager promises to their axes. There were at least two hundred of them, and though rumor had described them as flux-ridden and liver-sore and spent, they were now in possession of a kingly treasure, with the promise of an elephant and a chance of bloodshed, and looking fresher and gayer by the instant. The archer had his twenty men, their shooting skill blunted at close range, their daggers inadequate. High up on the walls of the city another company of archers looked down, fine marksmen all and as prone to outrage at the scandal of the looting of the elephant, but their grasp of the situation at a bowshot was no doubt limited. Meanwhile, the bek’s personal bodyguards, thick-skulled glowering Colchians, owned impenetrable minds and loyalty only to their paymaster.

“Must you,” Buljan said in a distracted way, watching the magnificent old animal swing down the ramp with its womanly gait, ringing like gongs the sawed planks each as thick as a strong man’s wrist. When the captain had last seen the beast she was caparisoned and painted like a whore at carnival, but now she came wearing nothing but the rich gray terrain of her hide, scarred and dignified and so replete with power in the shifting under the skin of her monstrous musculature that she seemed to the captain to embody the antiquity and might of the kaganate—and in her imminent journey from the embankment to the barge that stood waiting to tow her up the river to the home of the Northmen, where she would surely perish in the cold and the dark, that empire’s passing. “I wonder how?”

And Buljan drew his own short sword and before the captain of archers could flinch or turn heaved it up into the soft exposed region just under the captain’s arm. There was no pain, at first, only heat and the rank breath of Buljan whistling through his teeth, and an unbearable sadness, and then one of the Northmen laughed as the captain sat down on the dock, and then it hurt. The Rus moved in a boiling tangle like a troop of murderous monkeys the captain had once seen ravaging a village, far away to the southeast in Hind, and his men unsheathed their daggers, and the captain closed his eyes. To his great surprise his death was accompanied or heralded by the sounding of ram’s horns, which struck him as a little showy, perhaps, and then there was a silence that accorded more with his expectations, and he opened his eyes and saw his men standing with daggers ready and the Northmen milling, shoulders together and sullen-eyed like boys caught at mischief. From the shore there came a coin-chink of stirrup and mail and harness bit, chiming over and over like some kind of bellicose carillon, and he turned and saw an army, the army, his army, wave after wave of riders and footmen pouring and clattering onto the embankment and filling in every inch of space between the wharves and the walls of the city. And in their midst or at the head of them rode a slender young man with head erect and mouth full and scornful.

He rode down the ramp and as he passed the elephant, reached up to stroke her flank. He reined his horse by the captain of archers and looked down, a beautiful young man, breathing hard like a green recruit about to make his first bloody charge.

“Are you all right?” he said to the captain of the guard.

“I may well die,” said the captain of archers, feeling as grateful for the sight of the young man as for a cold drink of water. And in fact the youth now threw down a waterskin, with a solemn nod. Then he leapt from the back of his horse and rushed at Buljan the usurper without warning or art, chopping with his sword as if it were an ax. It was an ugly move, and Buljan, who was among the best swordsmen of his people and generation, easily ducked it and sidestepped. The sword came whistling down and lodged with a discordant twang in the timber of the dock, and while the youth struggled to free its edge from the grip of the hard wood Buljan leaned forward, peering curiously at the face of the young man, and then catching hold of the youth and wrapping his long arms around him did something that struck the captain of archers, and no doubt every soul animal or human on the wharf that afternoon, as strange: he smelled him.

“You,” he said, dismayed or delighted, it was hard to say. The youth struggled, kicking and squirming and trying to reach around with his teeth and bite at Buljan, but the usurper held him easily and fast. He laughed a false laugh that held genuine bitterness, and turned to the army that watched motionless from the shore. “This is your new bek?” he called out. And he unsheathed his own dagger now and held it to the fine young throat. “This is no bek. This is the mother of a bek. She carries my seed in her belly!”

The dagger flashed and his arm came up. It never came down. A thick gray vine snaked down and took hold of it and, like a Rus ceremoniously killing off an amphora of wine, hoisted Buljan into the air and brought him down against the dock. The breath huffed from Buljan’s lungs and certain of his bones could be heard to break, and he lay there stunned, and no thing but the river moved or made a sound. Then Buljan’s wife screamed as the elephant laced its trunk around his ankles, hoisted him again into the air and slammed him down once more, ensuring the fracture of skull and vertebrae. The elephant appeared to enjoy the business and repeated it several more times, and when the captain of archers at last averted his gaze from the mass of pulp and leather he saw that a ghostly scarecrow clad in black had appeared behind the twin daughters of Buljan to blindfold their faces with his long white fingers. At last the elephant lost interest or took pity and dragged the broken body across the timbers, leaving a bloody trail, to lay it—with a tenderness in which a sentimental man might infer a note of apology—at the feet of the widow of Buljan.

The youth rose shakily to his feet and raised his sword and turned, slowly, around and around. By now the Rus were scrambling into the barge intended for the transport of the elephant, showing considerable alacrity and even a cowardly grace. The youth pointed to Ragnar Half-Face, who in his haste to flee had stumbled over several bolts of fine blue silk of Khitai, and a big man with skin the color of tarnished copper ran after him, surprisingly fleet for a gray-hair, and caught the Rus chieftain, and dragged him back to face the young man.

“Who are you?” Ragnar said.

“I am Alp,” said the young man, and the captain of archers knew him then, recalled from some parade or guard detail the piercing green eyes of the boy’s mother’s people.

“You are not Alp,” Ragnar said. “You resemble him. But Alp died puking blood over the side of my ship, chained to a rowing bench.”

The youth reached for his sword, but now the pale hand of the scarecrow shot out and took hold of the young man’s wrist.

“Enough,” he said.

“You will die a far more unpleasant death still,” said the dark-skinned giant, “unless you return all that you have looted from the shores of this sea.”

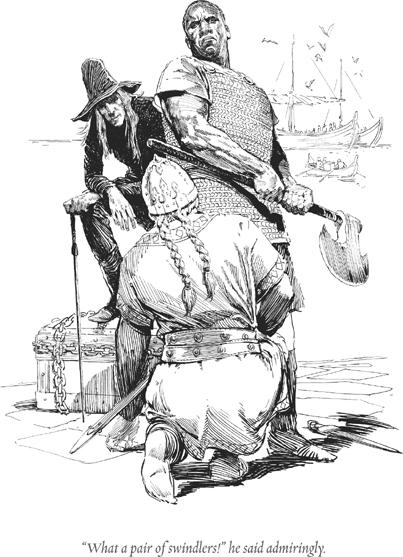

The giant pushed him to his knees, and Ragnar looked down, his greasy yellow braids tumbling around his face. Then he looked up again with a mercantile glint, his half-face twisted as if in wry pleasure, looking from the pale man to the dark.

“What a pair of swindlers!” he said admiringly. “Gentlemen of the road, hustling a kingdom! Who are you?”

But if any reply was made to this question, the captain of archers never heard it.

That night Zelikman and Amram welcomed the Sabbath in the dosshouse on Sturgeon Street, with Hanukkah and Sarah and Flower of Life and a number of infidel whores who saw no greater harm in marking the sacred time of the country than in accommodating the needs of its men. The women and men alike covered their heads and hid their faces behind their hands and blessed the light. When the candles had burned down and the first of the night’s clients—foreigners, sailors, Christians and the lapsed—had arrived, Amram took to a bedroom with Flower of Life. One by one everyone got up from the table and went through the curtain to work, leaving Zelikman and Hanukkah alone.

“Where will you go?” Hanukkah said.

“I am the great sage who suggested we try the road from the Black Sea to the Caucasus,” Zelikman said. “It’s his turn to choose.”

“I could come with you,” Hanukkah said, pulling at his pudgy chin as if trying out the idea on himself.

Zelikman reached over and patted him on the knee. “You have a woman to redeem,” he said.

“And no gold to redeem her with.”

“Come with me,” Zelikman said, and they wound down the crooked hall behind the common room, to a small chamber, hardly larger than a privy, in which Zelikman planned to spend the night, not willing to spoil his own melancholy or with it the pleasure of Amram. He opened one of his leather bags and took out a sack of dirhams mixed with gold scudi and Greek coin that represented about half the payment he had received for his services to the new bek of Khazaria, and handed it to Hanukkah.

“I doubt she’s worth half that,” he said irritably. “Now go away and leave me alone. I wish to sulk.”

Hanukkah embraced him and kissed him, his breath vinous and his emotion nettlesome to Zelikman, who sent the little bandit on his way with a kick in the seat of his breeches. Then Zelikman knelt on the floor beside his cot and passed an hour inventorying and consolidating his herbiary and pharmakon, thinking about his father, away in the stone and fog of Regensburg, and how he would interpret or respond to the abject, heartfelt, even florid letter of apology and recantation that the leathern old Radanite had extracted from Zelikman as payment for allowing first him and then the kagan to pose as one of them. When his gear was packed he took out his pipe and the last of his bhang. For a long time he sat, listening to the barking of dogs and to the sad fiddling of the rebab, thin and plaintive in the snowy air, with the flint and striker in his hand. He was about to light the pipe when he heard a footstep outside his door. He reached for Lancet but she slipped into the room before he could get his fingers around the hilt. She had come to him as a girl, in a long wool skirt and a wool coat, hood trimmed with spotted fur. There was snow on her eyelashes and on the fur trim and about her an iron smell of snow. He stood, and they looked at each other, and then stepped quickly together as if stealing an embrace against the coming of an enemy or a watchful governess.