Georgian London: Into the Streets (12 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

I presume

you haven’t lately passed through Lincoln’s Inn Fields, otherwise I think you would have animadverted on a new-fangled projection now erecting on the Holborn side of that fine square. This ridiculous piece of architecture destroys the uniformity of the row and is a palpable eyesore.

But Soane’s star was in the ascendant, despite his apparent unpopularity and some bad misjudgements. He was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy, which had decreed that comments or criticisms of living artists were not to be allowed in lectures. Soane couldn’t help himself, and he attacked his young competitor Robert Smirke for the ‘

glaring impropriety’ of his designs for the new Covent Garden Theatre. The audience was shocked, and began to hiss. Soane defended himself: ‘It is extremely painful to me to be obliged to refer to modern works

.’ The subsequent fallout led him to suspend his lectures.

Such small matters, however illuminating, were not part of Soane’s grand plan. When his sons disappointed him by not wanting to follow in his footsteps, he conceived the idea to gift his house and collection to the nation; in 1833, he obtained an Act of Parliament to do so. A comprehensive guidebook of the house by John Britton stated, in 1827, that it had not been ‘

adapted for spectacle

and display but constructed from the beginning as an architecture of spectacle and display, a theatre of effects’. By leaving his house as a museum ‘

in perpetuity’, Sir John Soane (as he would become) prompted some to ‘wonder what sort of perpetuity he imagined? Was he thinking of a hundred or a thousand, or a hundred thousand years? A hundred would show him a prudent man, a thousand a vain man, and any longer term, a megalomaniac

.’ He was probably all three. Sir John Soane’s house is still preserved by that Act of Parliament, and can be visited today.

The variety of residents in Lincoln’s Inn Fields was an exception in an area of London otherwise dominated by the law. It lies just to the west of Chancery Lane, which is the spine of legal London. At the head is Gray’s Inn, on Holborn. At the base nearest the river sit Middle and Inner Temple, inside the City limits. Outer Temple lay outside the City limits and was gradually phased out. Thus, the Inns of Court straddle the City boundaries, but they are a settlement quite apart from both the City and Westminster.

During the Elizabethan period the Inns flourished, becoming a busy camp of young men all eager to learn the law and to acquire the polish of London life. Law was not only a functioning machine but a web of theory to be moulded in the best way to serve both the people and the state. Each of the Inns had a hall for communal eating, a chapel for worship and a library for reference. Surprisingly, they offered relatively little instruction in the law; boys who wanted to learn it took private tuition. Without a formal structure of education and with no qualifying exam (introduced in 1852), getting called to

the Bar was as much about personal charm and intellect as it was about knowledge of the law and ethical soundness.

During the eighteenth century, two men emerged from the Inns of Court who were utterly different, yet together saw the emergence of the ‘modern’ system of British legal representation. They made important advancements, not only for themselves but for the profession and for the state. They were also both outsiders who made their way up the system through a combination of hard work and intellect.

Thomas Erskine was the youngest son of the Earl of Buchan. Beautiful and clever, he had gone to sea at fourteen after a basic grammar school education in Scotland. The sea wasn’t to his taste, so he raised enough money to buy a commission in the army. Aged twenty-two, he met James Boswell, who would later record that the young officer ‘

talked with a vivacity

, fluency and precision so uncommon, that he attracted particular attention’. This fluency and ability led Thomas to consider a legal career. He put his name down at Trinity College, Cambridge; three years later, he obtained a degree without attending lectures. Meanwhile, he installed his young wife in Kentish Town with their growing family, so that his annual allowance of £300 could be eked out, whilst he studied law. By the summer of 1778, Erskine had been called to the Bar and his charm and intelligence brought in the cases thick and fast. He soon gained a reputation as a liberal intellectual who believed in freedom of speech and the press, taking on cases in which he and his clients emerged as the victors owing to his mastery of ‘

the art of addressing a jury

’. In 1792, he defended Thomas Paine when he was charged with seditious libel after the publication of the

Rights of Man

. Although he was unsuccessful in this case, Erskine famously lectured barristers on the need to take on even unpopular and risky cases.

Erskine came to prominence through charm and oration whilst assisting Lloyd Kenyon, who was the opposite of his young protégé. Born in Wales in 1732, he served his term drudging for an attorney, learning the rules of Chancery law. He was called to the Bar young, in 1756, but couldn’t get any work because he was no good as a public speaker and had few contacts. He was appointed Master of the Rolls, which is the right-hand judge serving the premier judge, Lord Chief

Justice. In this position, he was in charge of the tedious but important arm of Chancery law, something he was eminently trained for. His work became the benchmark others strove to follow. Four years later, he succeeded the Earl of Mansfield as Lord Chief Justice, a post he held until his death. He was hugely admired as a judge, and played the perfect counterpart to the charming persuader his assistant had become by being patient, full of knowledge and ‘

of the most determined integrity

’.

A career in law during the eighteenth century was random and opportunistic, but Erskine and Kenyon represent the best of it – and also the emergence of our modern court systems and the move towards trial by jury.

Erskine and Kenyon are fine examples of the sort of men the Inns were producing during the eighteenth century, but not all their colleagues were quite so diligent. The area of the Inns was an affluent one, and there were large groups of young, privileged men with time on their hands, who enjoyed all that the area had to offer. The Royal Society had moved here in 1710, when Isaac Newton negotiated the purchase of a small house in Crane Court just north of Fleet Street. Samuel Johnson lived nearby, in a house which is now a museum in his memory; his local pub, The Cheshire Cheese, is still standing. Mrs Salmon’s Wax Works stood near the entrance to Middle Temple, where one might see waxworks of kings and queens, and where an automated waxwork of ‘

Old Mother Shipton

, the witch, kicked the astonished visitor as he left’. On the south side of the road near Temple Bar was the favourite coffee house of the young men of the Inns, called Nando’s.

Between 1710 and 1712 a group of young men, mostly in their late teens and early twenties, would use Nando’s as a focus for their violent gangs, called the Mohocks. The Mohocks were active throughout the year, mainly along Holborn and the Strand and in Westminster.

They drank heavily

, smoked marijuana and tried to act like the savages they took as their namesake.

Marijuana was in use as a recreational drug in London from the late seventeenth century. Robert Hooke lectured on it at the Royal Society in 1689/90 and noted that it rendered the user

…

unable to speak

a Word of Sense; yet is he very merry, and laughs, and sings … yet is he not giddy, or drunk, but walks and dances … after a little Time he falls asleep, and sleepeth very soundly and quietly; and when he wakes, he finds himself mightily refresh’d, and exceeding hungry.

Hooke obtained his score from a sea captain in a coffee house, no doubt along with many others.

The Mohocks committed acts of street violence on both men and women, but although their victims appear randomly chosen, the damage inflicted was not. Watchmen were badly beaten and women humiliated. Two women were stabbed through the lower lip, perhaps in a bizarre piercing ritual.

When caught, the men were all young ‘gentlemen’ and often associated with the Inns of Court. Bail was set at hundreds of pounds. The ringleader of the 1712 violence was thought to be Lord Hinchingbrooke, but his arrest did not stop him becoming a Member of Parliament the following year. Some of those arrested for involvement in the violence were later called to the Bar.

Students didn’t only learn the law, but also dancing and fencing and various other social skills thought necessary. In 1744, a court case at the Old Bailey recorded the trial of Ann Duck, born in ‘

Little White Alley

, Chancery-lane, the Daughter of one Duck, a Black, well known to many Gentlemen in our Inns of Court, by teaching them the Use of the Small Sword, of which he was a very good master’. Ann went on to teach young men the use of the small sword too, but as a prostitute.

As a community of young affluent men, the Inns of Court were a natural magnet for prostitutes of the better sort. The ward of Farringdon Without contained over seventy bawdy houses – more than half the City’s brothels in the early part of the century. There was speculation that educated young women who had fallen on hard times ventured into longer-term agreements with the students, flitting in and out of Temple or Lincoln’s Inn with their faces masked. Common prostitutes also sought keepers amongst the students and barristers, such as the ‘

luscious’ Miss Sh—rd:

And so, even the respectable legal engine of London hosted gangs, drug takers and prostitutes, making many barristers not so far removed from those who sat in the dock.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the margins of the City were little more than a varied combination of hotchpotch urban overspill, but soon the old houses and brothels were swept away in a frenzy of building and rebuilding. Only Temple and the Inns of Court remain almost unchanged since the early eighteenth century, when a new London had already run away westwards along the Strand.

3. Westminster and St James’s

Westminster is London’s second city. Since the twelfth century, it has been the seat of government and of the sovereign. By 1700, it was far from the grand administrative centre we know now. It was a small settlement which had grown up around ancient palaces, religious houses and a school. Whitehall Palace, built by Cardinal Wolsey and appropriated by Henry VIII, was the sprawling home of the civil service until it burned down in 1698 after a maid left sheets drying too close to the fire. Inigo Jones’s Banqueting Hall was the only building to remain intact. The opportunity to rebuild to any coherent plan was missed, as John Gwynne, the man whose grand plans for London came to nothing, observed: ‘

why so wretched

a use has been made of so valuable and desirable an opportunity of displaying taste and elegance in this part of the town is a question that very probably would puzzle the builders themselves to answer’.

Nearby, the medieval Palace of Westminster sat by the river and was used for the two Houses of Parliament. Today, Parliament Square is a jostling roundabout, with police in high-visibility clothing restricting access to only the chosen few. But in the eighteenth century, Parliament struggled on with an increasingly shabby and dilapidated set of buildings surrounded by open ground and mixed housing, much of the latter dating from the Middle Ages. The faded grandeur of the palace and the nearby poverty was revealed nowhere more starkly than just behind Westminster Abbey. Beyond a smattering of new streets were the slums and ugly open ground of Tothill Fields, where boys played football and pigs rooted in the cinder heaps. It was a dangerous area, and Westminster School, whose pupils had included Christopher Wren and John Locke, was not immune to the atmosphere. In the autumn of 1679, a group of

‘

Gentleman Schollars’ were tried for kicking to death a bailiff who had entered the school to make an arrest. ‘After some mature consideration of their Youth and Quality

’ they were let off, but the young scholars were a constant presence in the taverns and eating houses around the school, where they mixed with every type of Londoner. Near the school, a slum on Pye Street became known as The Devil’s Acre. The palace and the abbey were no more than ‘

a stately veneer for the hovels crouching behind’. From these ‘labyrinths of lanes and courts and alleys and slums, nests of ignorance, vice, depravity and crime

’ issued forth Westminster’s underclass.

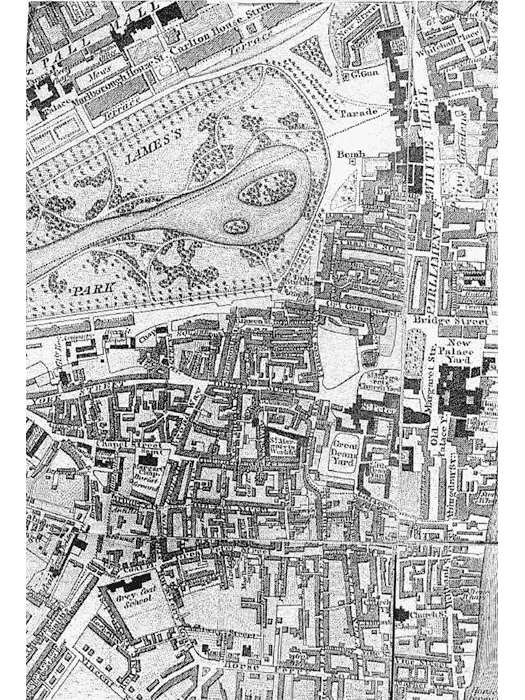

Westminster, detail from John Greenwood’s map, 1827

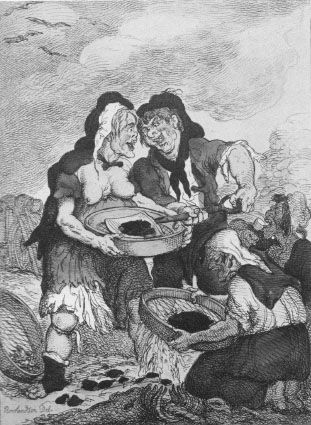

The poorest women of this slum sifted the cinder heaps for anything still worth burning. Some were also the lowest class of prostitute, the filthy scarecrows of caricature, with ragged and toothless mouths. Many were dependent upon charity, and St Margaret’s workhouse was one of London’s oldest. St Margaret’s is the official church of the

Houses of Parliament. The associated workhouse moved locations through the century but the institution in Little Almonry pioneered maternity care in the 1740s, offering courses in midwifery at vastly reduced rates for women who were to work amongst the local poor. They were taught alongside the young male students, who paid handsomely for their lessons and would go on to lucrative careers as ‘man-midwives’. The contrast of rich and poor in the area meant the Members of Parliament were reminded constantly of their duties to the less fortunate members of society. They had only to walk out of the Palace Yard to see the cinder-women and infants scavenging on the Tothill laystalls. Gaggles of poor children trailed behind an older brother or sister, left in charge while parents worked.

On a Saturday in 1762

, in a run-down alley near Tothill Fields, Mary Flarty left her toddler Jerry with five-year-old Anne Ellison. The alley had no traffic, and seemed safe for young children. Jerry tried to use the special low seat for youngsters in the communal privy, and fell into the cesspit. Although the community rallied immediately to retrieve the boy, Jerry was already dead. Cesspits, wells and carriage wheels were all waiting for a moment’s inattention.

‘Love and Dust’, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1788, a caricature of paupers on Tothill Fields, Westminster

The government’s awareness of the social problems of poverty was growing. Urban poverty was becoming more obvious and pressing as the population increased. Riots, though often attached to political causes, were usually closely linked to empty bellies. The greatest of these, the Gordon Riots, where Parliament was attacked by a rampaging mob, made London realize it needed a police force. Although many in the government saw the police as little more than a standing army, they realized by 1780 that without a police force London would be ungovernable. With greater organization came bigger and better prisons, built on new designs. Nearby, to the west, was Millbank, home of the horse ferry and ‘

so called from a mill

on the bank of the river’. There the forbidding Millbank Prison was built in 1821, to a design by philosopher Jeremy Bentham. It was a terrifying labyrinth in which even the warders got lost, and the prisoners used the bizarre acoustics to communicate between cells. It held large numbers of prisoners waiting for transportation; for many years, a prison hulk lurked On the river outside.

Behind Westminster, open land lay undeveloped as far as Knightsbridge. When Charles II came to the throne, in 1660, he chose to live in St James’s Palace and left behind the medieval architecture, slums and cinders of Westminster for the countryside. He created the Arcadian St James’s Park, with water features and walks. He also created a demand for new housing of the smartest sort, resulting in the development of St James’s Fields. This was housing for London’s most fashionable, including rich foreign visitors in temporary lodgings. When the business of the day had been dispensed with, including the coffee house visit and parliamentary business:

…

the evening is devoted

to pleasure; all the world get abroad in their gayest equipage between four and five in the evening, some bound to the play, others to the opera, the assembly, the masquerade, or musick-meeting, to which they move in such crowds, that their coaches can scarce pass the streets.

These ‘new rich’ were not entirely self-serving. As in Westminster, there was a growing awareness of the division between rich and poor. The spectre of poverty was never far from even the grandest doorstep, and even the palaces admitted chars to do the washing. The cheek-by-jowl relationship of Westminster and St James’s nurtured some of the country’s most remarkable men and women. Thinkers, politicians and fashionistas all congregated in this rapidly growing district, the polite area of London, so different from the City’s mercantile origins.

After the Reformation, Protestant England used local parish officials to distribute part of the land tax as charity, uniting Church and State in providing for the poor. The Poor Law of 1601 meant that to obtain parish charity an individual had to belong to that parish. Belonging was not as simple as taking up residence: poor would-be settlers were often removed by parish officers, and it was a widely held belief that the Poor Law gave those living in poverty an incentive to continue their breadline existence without working.

Vagrancy was a preoccupation of the Middle Ages, when decent citizens feared tinkers, pedlars and other itinerant workers. Their estrangement from community ties was seen as a threat to society, and they were associated with decayed morality and petty crime. Yet as the country entered the modern era, migration became essential. Seasonal workers, domestic servants and those simply wishing or needing to find employment gravitated towards towns – London, in particular. ‘Settlement’ in a new parish was gained through a complicated system of qualification. By 1700, settlement could be gained through birth, marrying into the parish, serving an apprenticeship there, working there for a year or serving as a parish officer.

In the medieval period, when towns were small and prosperous, poverty was more a rural phenomenon, experienced when crops failed, or murrains killed off the livestock. The system of poor relief which emerged in the mid-sixteenth century concentrated on taking care of the sick or those who were old and infirm with no one else to care for them. But as towns, and particularly London, grew in the late seventeenth century, urban poverty – unrelated to seasonal highs and lows – became part of the landscape. St Margaret’s parish had built workhouses in Tothill around 1624, to house the old and infirm but not the able-bodied poor, who were supposed to be able to shift for themselves.

Urban poverty was often more desperate than rural poverty because urban life was more dependent upon money. In the countryside, foraged food and wood for fuel were available, even if in short supply. Those who paid rent paid it quarterly, or exchanged their labour for housing. In the rapidly growing London of the eighteenth century, however, people rented rooms by the month, week or even day. The available fuel was coal, which cost money. Food was brought into the capital and retailed. In order to appear employable, particularly in service, clean linen and tidy clothes were essential. Life in London was expensive.

Appearing poor was a thing to be avoided at all costs. John Loppenberg was a servant in Westminster and later St James’s who used to go to the ponds at Paddington early in the morning to wash his linen:

I was ashamed

to be seen doing it by any body, because it was torn and ragged. I went to one Pond, and saw People there, so I went to another … I hung my Shirt up to dry, and walked to and fro while it was drying, and saw two Men walking about; I threw the Shirt from me least they should laugh at me.

John Loppenberg was typical of many London servants who lived on the edge of respectability and were always in fear of ‘being out of a place’. People arrived from overseas, or elsewhere in Britain, because they were following an employer. Should they fall on hard times and throw themselves on the mercy of a parish within that year, the overseers were perfectly within their rights to move them along – by force, if necessary, though this happened relatively rarely.

The Season, stretching from March until the end of July, saw peak demand for employment in Westminster and St James’s. Anyone with pretensions to fashion or business was in town for those months, requiring servants, washerwomen, errand boys and porters. They also provided work for shoemakers, tailors, prostitutes and thieves.

In the hard winter months

, when working the streets was impossible, and there was less demand for jobbing servants, workhouse numbers rose by up to 25 per cent.

In wealthy London, the urban workhouse developed rapidly after the Workhouse Act of 1723. The Act meant, in brief, that in order for the destitute to claim parish charity they had to enter the workhouse and ‘work’ for the good of the parish. ‘Outdoor relief’ (payments made to people so that they could remain in their own homes) was available, but this didn’t help people like John Loppenberg if they were to lose both their job and accommodation at the same time. But workhouses did acknowledge the new developments in medicine and social welfare. There were wards for pregnant women, as well as labour wards, wards for the sick, the healthy, same-sex wards and rooms for the married. Inmates wore uniforms bearing the parish badge. Unmarried mothers were sometimes made to wear yellow gowns. Those who behaved badly had to wear special uniforms or distinctive badges.

As the century progressed, workhouses became more developed and more socially conscious; they were no longer housing just the

disabled, infirm and aged, but men and women who had fallen on hard times, as well as their attendant children. In 1817, St Martin-in-the-Fields workhouse admitted two-thirds adults and one-third children.

The women made up

60 per cent of the adult population and stayed on average for six weeks, two and a half days. In contrast, the men averaged two weeks and six days. It is clear to see that there was a pattern: it was easier for men to get back on their feet. A third of the women of childbearing age who were admitted were in the later stages of pregnancy, and alone.